A visit to Studio 24 and a text with and about the grey master

Published in Nuda:Beyond

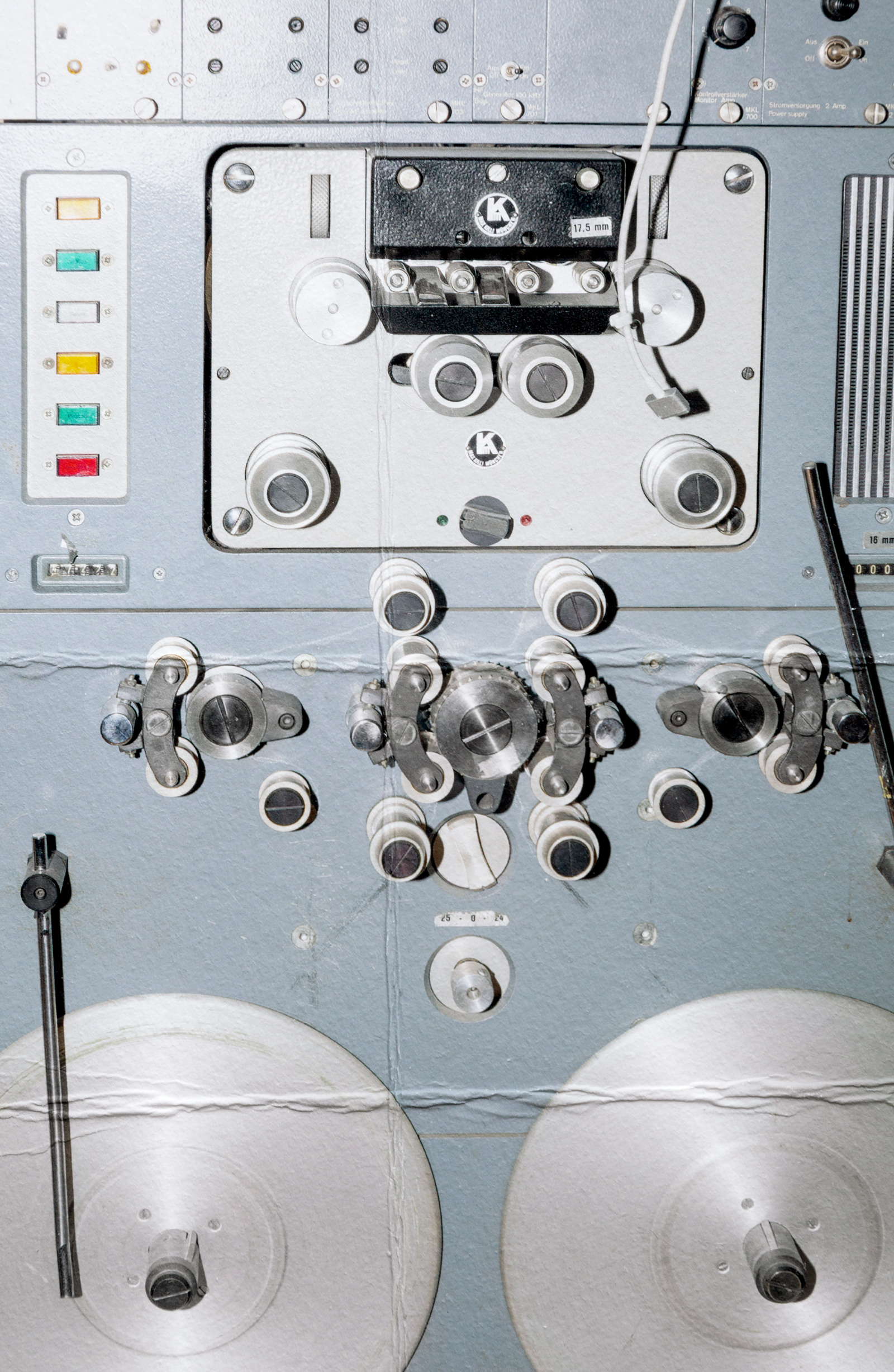

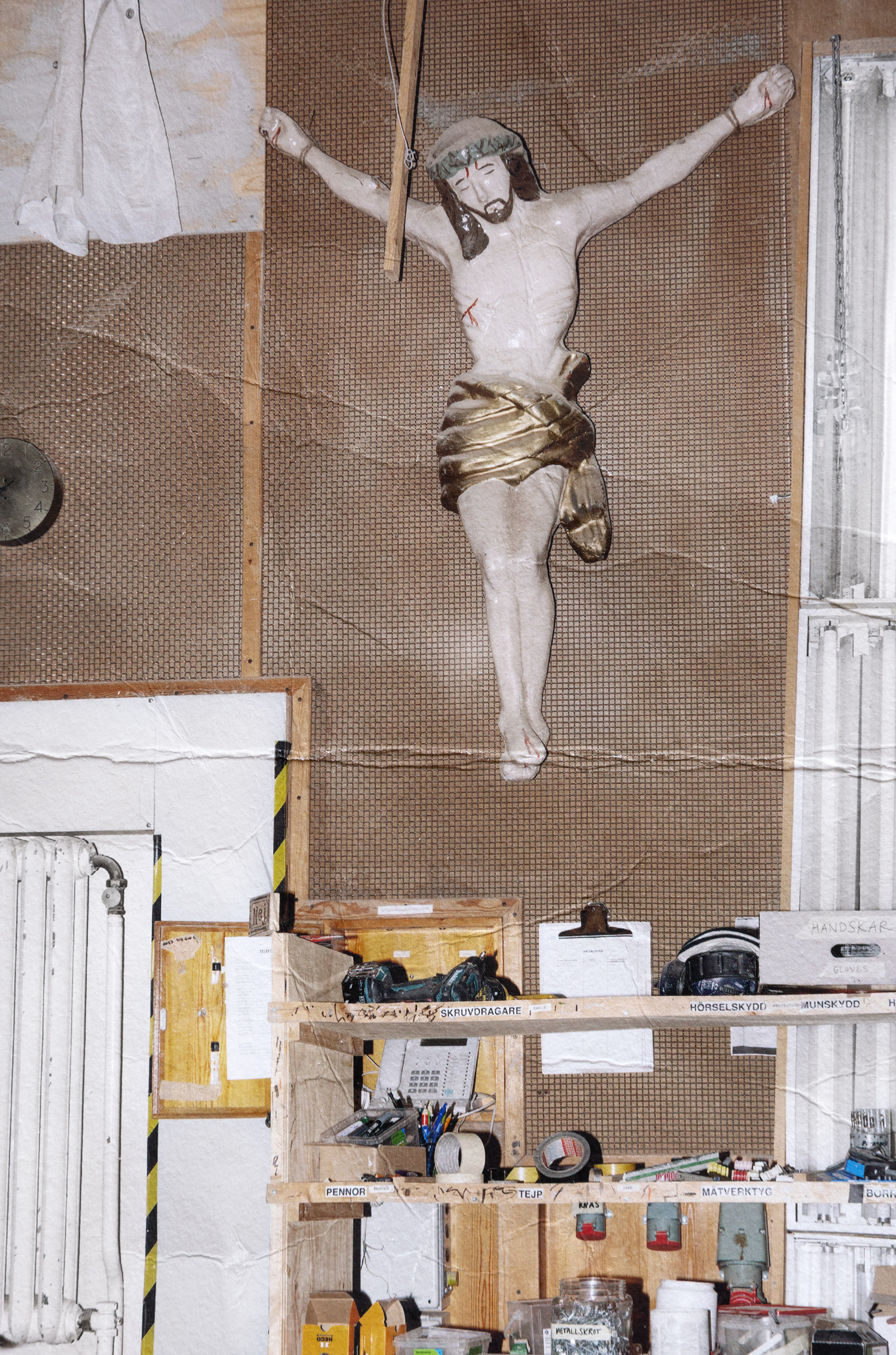

Roy Andersson does not believe in life after death. “Well, unfortunately I don’t. I absolutely don’t.” The 77-year-old Swedish film director states during our interview, made in relation to a visit to his now legendary Studio 24, at Sibyllegatan in Stockholm. All of his “Living Trilogy” films were shot here, including the fourth (a pun typical of Andersson) About Endlessness, which premiered at the Venice Film Festival in 2019 and won him the Silver Lion for best director. Andersson’s style is unique and unconditional, the camera simply does not move, and all scenes are shot using meticulously crafted tableaux in the tradition of trompe l’oeil. Within his studio, the director has created a universe consisting of washed out coloured landscapes, populated by pale-faced non-actors who express the longings and loneliness of humankind. Parts and pieces depicting grey houses and desolate streets lie scattered around the walls.

We begin by talking about the dualism within Andersson’s cinematic language, which is based upon building realist landscapes from scratch. “I want to make reality stylized”, he explains. “Or maybe condensed in another word. In one sense, I would describe my films as pretty realistic but condensed and clarified. My goal as a filmmaker is to create cinema that clarifies, not obscures, our human condition.”

Andersson had his directorial break-through in 1970 with A Swedish Love Story. What was evident then, and has become even more obvious since, is that his narratives always develop a space where tragedy meets comedy. I ask him about this interstice and where the curiosity to depict it comes from. “I think it is about my personality. That humane and empathetic side, it is part of who I am. Let’s be honest, man is pretty helpless. It is touching to recognise that helplessness, and there is a melancholy to it as well. All I can say is that I want to make the inherent vulnerability in people visible, but at the same time evoke feelings of warmth for them in their exposed situation. We all have a short time here on earth. There is both comedy and tragedy in that.”

goal as a filmmaker is to create cinema that clarifies, not obscures, our human condition

Olga: Within that tragedy and comedy, your films also search for a space where grandiosity can be traced in the ordinary, and vice versa. But what do you, yourself search for in life?

Roy: I would say the most beautiful thing there is in life, is when someone is entirely absorbed in something. To be rife with dreams or expectations is a beautiful phenomenon and it is a very tragic loss when there is nothing left to be rife with. I would say that this is also what I work with, the sense of being full of something as a human.

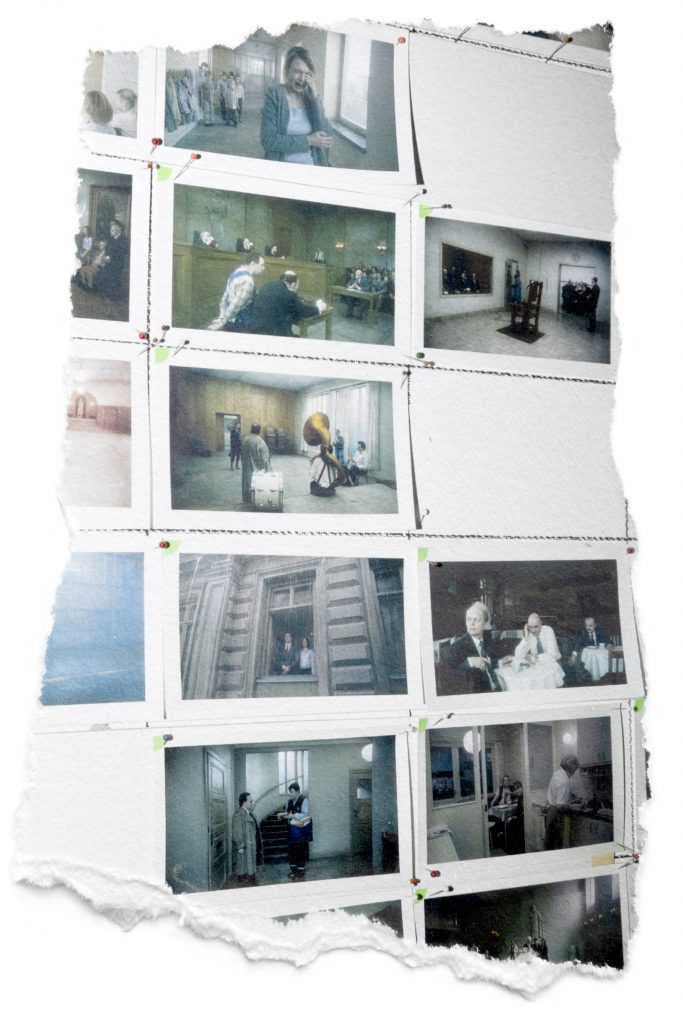

In About Endlessness, one of the characters is a priest who has lost his faith. Seeking help, he visits the doctor’s office and is rejected, due to the doctor being busy trying to catch the bus. The question of religion and people’s inability to recognise each other’s difficulties is a recurring theme in Andersson’s films. I ask what he thinks about when he builds his characters. “I feel that it is touching. The characters are tragic, but within they are vital – and this is important. It becomes important that they exist and that they have existed. I mean, life is composed of fragments, it is never possible to make a whole out of one’s existence. You get a piece here and a piece there and by the end you puzzle it all together. Life is fragmentary and so are my films.”

Olga: The scenes in your films are fragments in relation to each other, but they also work on their own. With the use of tableaux and static camera, every scene is like a painting that can be contemplated in itself.

Roy: I would like to move the camera more or to cut more, also since I have received critique for my static images. But every time I try, the result is inferior. And why do something that is inferior? So it will remain like this until I die, simply put.

But to say that there is no movement in Andersson’s film would be unfair. In Songs from the Second Floor, the first film in his “Living Trilogy”, almost every scene contains parallel actions. These are often put together in an anachronistic, absurd way where the dead and the living, or the history and the present, all collapse into one another. A man standing in the ruins of his company store (which he himself has burnt down), explains to the insurance company bureaucrats that the pile of ashes they are looking at was a Chippendale group. Meanwhile, a chain of self-flagellants walk outside the window, passing an inexplicable traffic jam whose honking horns can be heard throughout the film. “I think it is fascinating that there is more to man than meets the eye. And there are works, not just mine but others as well, that make life and existence open up. Works that make the little nooks and secrets of life visible. The theme of About Endlessness, I would say, is that life is endless. The riches of life are endless, or like in the scene where the boy says: ‘Nothing is ever destroyed, it only comes back in new shapes.’”

Let’s be honest, man is pretty helpless

Andersson’s films have often been described as philosophical reflections on life and what it means to be human. There will always be an inherent melancholy within art and the expressions it can take, be it painting or writing or whatever, he states. “I think it is about the fact that time passes. Everything in life is fleeing and that is where our anxiety and stress derives from. That everything is fleeing. And especially within our time now.” What makes Andersson’s films stand out in relation to so many other portrayals of the transience of life, is that they all have a distinct comic side to them. At certain points in the films you have to laugh in sheer self-defence in order to endure the mortal awkwardness that the scenes evoke. Failure to cope with Nazism, sexual rejection, and elaborate public executions are some of the recurring themes. And often the characters in his films stare back at us through the screen with a shy glance, as if asking: is this funny? “I am an incurable optimist. There is one thing that makes it possible to cope with life and that makes you attractive and that is humour. It is a weapon and it is a tool or at least it has been for me for many years. Humour is a wonderful survival tool. I got it from my father, he was a very humorous guy and an inspiration for me. And then I have always loved films who got this clever sense of humour.”

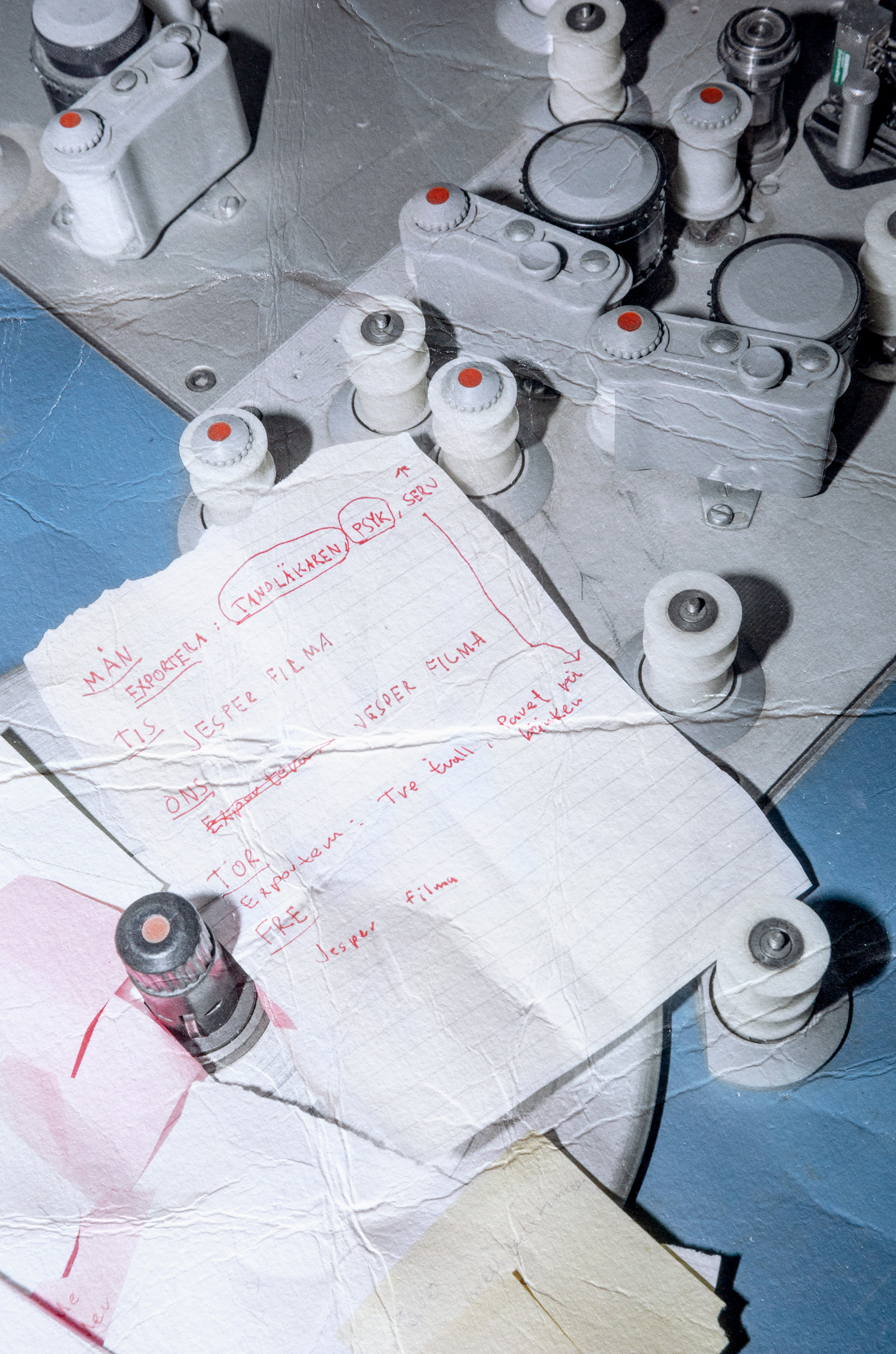

Apart from Vittorio de Sica’s The Bicycle Thief, Andersson seldom refers to previous filmmakers in terms of influence but instead draws on art and literature. He explains that the German movement Die Neue Sachlichkeit has been a huge inspiration, together with the Czech New Wave. Art is almost more important than film itself, he continues. We return to talk about the realism in his images where everything has been reduced to only the most important details, as if signalling a place, rather than depicting it. “It always begins with a sketch, sometimes I sketch carefully and sometimes horribly sloppy, but I make them in order to have a material to talk about and develop. There is of course an incredible amount of people involved in these scenes and for every god damn scene there is a sketch. From the beginning I wanted to be a writer and then painter and after that a musician. But then came that wonderful period in the history of European cinema, the 60’s and 70’s with new realism and French New Wave. And so I turned to filmmaking instead.”

Andersson has often been compared with the painter Edward Hopper. In the beginning scene of A Swedish Love Story, a grandfather rejects the idea of having to leave the hospital. “This world isn’t made for me” he says while chewing his ham sandwich. “It isn’t made for lonely people.” It could be argued that what Andersson really shares with the American artist, who often painted his subjects from a distance, is that they evoke empathy, not so much through one particular lonely human being, but rather through the very idea of loneliness. “Man’s situation and the sense of being lost fascinates me, it is sometimes funny but of course also very tragic. There is nothing to hold on to, nothing that is left. Everything is fleeing. Even man’s faith in God. We are not given that many years and we get lost in our short perspectives. One should be happy if one can believe in something for a longer period, but to be honest, most of the time we are pretty lost. I have found myself caught up in these themes of religion and I’ve thought a lot about people who claim to be religious, living with this sense of being close to God. I don’t know if I believe in that. I think man is consumed by all kinds of problems, even priests, if we return to the character in About Endlessness. Priests also have problems, beside their faith in God. I like the fact that I have created scenes that show questioning and doubt. Those are the scenes that I like a lot.”

Humour is a wonderful survival tool, I got it from my father

Talking to Andersson about art and his own view on life brings to mind the legend of the Chinese painter Wu Tao-tzu who was sent out by the emperor to depict the nature of Sichuan, renowned for its exquisite beauty. When he returned, he had no drawings whatsoever but instead painted mile after mile on the emperor’s castle walls, covering them with the most beautiful landscapes.

Olga: When watching your films, I feel that you move on the border between real and surreal. Social realism meets an absurd dreamlike world. What are your reflections on that?

Roy: I have let go of that realism I was so interested in when I was young. Instead I have turned towards the surreal. I find it to be more interesting since it can express so much more about our existence than a realist depiction ever could. Returning to Die Neue Sachlichkeit, it contains a condensed sense of realism, almost odd. The look exists within Swedish films from the same period as well, the 1930s. It is characterized by a certain clarity in the image, there are no shadows to hide in. That heightened sense of realism makes it surreal, or dream like.

When discussing the works of Andersson with the filmmaker himself, it is striking to realise that few other directors have created the same feeling in viewing. When watching a Roy Andersson movie, you enter his view of the world. The “Living Trilogy” depict people’s inability to connect with one another, and so there is a certain irony and beauty to the fact that Andersson has succeeded in precisely this dilemma. While watching, you cannot help but feel that this is really what being human is all about, since the tableaux and the people inhabiting them together create a deception so forceful that it is impossible not to be overwhelmed by it. When leaving the darkness of the cinema, you will stumble into your own perception again, while your eyes slowly adjust to the light outside. But Andersson states that he isn’t done yet. “People’s disorientation leads to absurd situations. And to portray people in absurd situations heighten the sense of being disoriented. It is so interesting to move beyond the realistic. To create realism within surreal situations, that is something I want to get even better at. And there will be more films on the theme of being lost.”

Olga: Will there be more?

Roy: I think so.

for every god damn scene there is a sketch

Roy Andersson does not believe in life after this. And having become a seminal influence on generations of Swedish filmmakers, it is difficult to see that he would ever pass on to the other side. The legend of the Chinese artist states that he one day grew old and tired of the emperor, humans, and everything. He then took his brush and painted himself one last lustrous landscape and walked into it. And maybe Andersson will one day take a step into one of his own grey tableaux and disappear like a small pale-faced dot beyond the distant horizon.

| Photography | Frida Vega Salomonsson |

| Words | Olga Ruin |