according to the archaeologist Bo Gräslund

Bo Gräslund is professor emeritus of archeology at Uppsala University. Born in 1934, Bo has dedicated his long career to researching pretty much every era of prehistoric and ancient times, from a number of perspectives – issues like climate and population, social aspects, ideology, epidemiology, nutrition, human evolution and biological factors in human behaviour have all been covered in Bo’s work. For the last eight years, however, he’s been completely absorbed by a single project: the epic poem Beowulf.

The Beowulf saga is part of our world’s literary heritage. The sole remaining version of the story is believed to have been written down in Old English at the beginning of the 700s and is commonly thought to have been composed by an Anglo-Saxon Christian poet, as a mostly fictitious tale. But when the matter of this historical epic’s background undergoes critical examination, this stance becomes untenable. Bo’s research shows that Beowulf was most likely orally transferred as a singular epic from eastern Sweden to East Anglia around 600 AD. This realisation bestows the poem newfound credibility as a historical document. It’s not just a fairy tale, it’s a testimony from times past.

The story takes place in the heathen Nordics of the 500s and describes a hero who fights off a number of horrible beasts. We get to experience ceremonial life in princely palaces, tag along on bloody rampages, share the times’ outlook on life and witness heathen cremations and funerals. By matching the story’s descriptions with geographical places, archeological findings and historical knowledge, Gräslund has managed to solve the saga’s riddle, precisely placing it in time, letting it shed light on historical phenomena and events formerly shrouded in mystery.

Bo: I think there’s too much specialisation in science today.

Nora: Isn’t archaeology fairly interdisciplinary?

Bo: Not sufficiently. Archeology maintains excellent partnerships with the natural sciences but not enough with the humanities and the social sciences.

Nora: Would you begin by telling me something about the Beowulf poem and its history?

Bo: Where to start? Should I tell the usual story? Or my interpretation of it?

Nora: Maybe you could start by briefly summarising the story?

Bo: Beowulf is a poem preserved in Old English, commonly thought to have been authored in England around the year 700. It’s been known since 1820, when it was first translated to Danish, and it has since been translated into more than sixty-five languages. The world in which the story first became public knowledge was dominated by the United Kingdom, culturally and economically. No one, not even in the Nordics, could imagine such a glorious tale being anything other than English, and that’s still where we stand. But nothing in the poem is about England – it all takes place in Sweden and Denmark in the 500s, two-hundred years before it was supposedly authored in England.

Nora: So how come previous research has claimed the poem is English? Beowulf does hold a position in history as an iconic English text.

Bo: One reason is Swedish and Danish archeologists never seriously taking on the task. We haven’t applied the knowledge necessary for cracking the code.

Nora: When you say “cracking the code”, what do you mean?

Bo: It began with Gad Rausing, the Tetra Pak billionaire, who was also an archeologist. In 1985, he wrote an essay pointing out how the names of some places in Beowulf appear on the Swedish island of Gotland, making the claim that there was no doubt of Beowulf taking place on the island. I soon realised that one of the largest palaces of the time, known as Stavars Hus, was located in the same area near Bandlundviken pointed out by Rausing. This had verifiably burnt down in the mid-500s, just like the royal court did in Beowulf, and just like in the poem it was situated saewealle neah, meaning “near the seawall”, near the mighty Littorinavallen, a geological beach wall from the Stone Age. There’s also mention of Beowulf sailing off to Denmark under beorge, Burgen being the name of Littorinavallen on the north side of the bay. The poem also describes how the snake burns down leoda fæsten, “the people’s fortress”, which, assuming we’re on Gotland, couldn’t possibly mean anything else than the gigantic hillfort Torsburgen which was burned down by the enemy around this time.

Rausing himself followed Beowulf’s sailing route from Gotland to Denmark. Previously, the assumption was made that Beowulf sailed to Lejre on northern Zeeland. But if you do like Rausing and follow the poem’s description of Beowulf’s nautic voyage, how he suddenly sees large, steep white cliffs, those could only be the enormous chalk cliffs of the Stevns peninsula on eastern Zeeland, heading toward Praestö Fjord. The poem also describes how Beowulf and his twelve warriors, all rattling shields and armour, walk on a beautifully laid road heading toward the Danish king’s residence. This, in its turn, could only be the unique Roman stone road near Broskov, right before the fjord. It’s as well made as old Roman roads in Italy, built in the 200s by Danes who’d learned to make roads while serving in the Roman army.

Nora: Going back to the poem itself, why does Beowulf make the journey to Denmark?

Bo: When Beowulf hears rumours of the Danish king Roar being tormented by a beast, Grendel, who breaks into his residence at night and devours his people, he decides to travel there to assist in killing off the monster. When everyone is off to bed, the beast appears, snatching one of Beowulf’s men, devouring him right on the spot. Beowulf then grabs Grendel, who eventually breaks free but loses the arm in the process. The following night things go off again, with Grendel’s mum rushing in to avenge his son, taking off with the king’s closest confidant. The morning after the whole crew goes out looking for the lake where they believe the beasts stay hiding. Beowulf leaps into the water and after a gruesome battle in the monsters’ underground lair he manages to kill off the mother and decapitate the already dying Grendel. The whole posse then returns triumphantly to the royal court. There, Beowulf receives great rewards in the form of gold jewellery and half a dozen horses.

The poem also provides vivid descriptions of the times’ flourishing courtly life. One easily forgets there was incredible wealth at that time in Scandinavia, a more remarkable society than the Viking’s in some ways. They sat in enormous banquet halls with beautiful tapestry covering the walls, with minstrels and bards singing poems to the tune of the harp. They drank imported Roman wine from Roman glass cups sparkling with colour. There was no comparison to these banquet halls in England, where the rooms were twenty metres long at most, while the Nordic ones could be forty and up to seventy metres.

Beowulf eventually becomes king over his people, the Geats, who couldn’t possibly be Goths but rather Gutar from Gotland. In the midst of it all a number of Swedish kings show up, and as matter of fact the poem accounts for at least four wars between Swedes and Geats. Some of the battles are very realistically depicted, in some cases as if by eyewitnesses. The latter part of the poem describes a fire breathing snake demolishing Beowulf’s land. Many loose threads in the poem are left hanging without explanation, which is typical of oral storytelling, rather than the purposely authored kind.

Nora: So you don’t think the story was made up?

Bo: Beowulf is a story based on real events, albeit with strong mythical elements which in retrospect might give a saga-like impression. But even the Icelandic sagas aren’t fairy tales in the modern sense, more like stories based on real life. The word “saga” simply means “said”, “something told” – an oral story. There’s no doubt that Beowulf was orally composed from its first line to the last. There are in fact no Germanic poems from this time that can be shown to have been composed in writing. Another matter is the fact that oral stories would circulate in differing versions and go through significant changes as they travelled through-out the ages.

The word “saga” simply means “said”, “something told” – an oral story

As the Frankfurt-based teacher and amateur archeologist Georg Ossegg explored the nearby Spessart forest one day in 1962, he felt a clear sense of déjà vu – it was as if he had walked that path before. Like many Germans, he was raised on the fairy tales of the Brothers Grimm, and the place he found himself in looked almost precisely like an illustration accompanying the tale of Hansel and Gretel. Sure, the trees had grown taller, but wasn’t this exactly what that forest looked like, where the children, their lumberjack father and their stepmother lived?

Hansel and Gretel is a folk saga about two siblings getting lured into the woods by their father as the family can no longer afford to support them. The children come up with a number of ingenious plans to make their way home but finally get lost and end up in the claws of an evil witch who lives in a gingerbread house and is hoping to eat the siblings. By the end of the story, just as the witch prepares to cook them, the children manage to trick her inside the oven, where she herself is consumed by the flames. The children escape and find their way home.

Ossegg’s arboreal revelation was the start of a serious scientific undertaking, in which the teacher went to the root of the tale’s historical aspects. Utilising various experiments and historical archives, his research manages to locate the family’s as well as the witch’s houses. Among other things he finds a rope tied around a tree in the woods, just like the tale describes. Through carbon dating he dates the rope, and along with it the fairy tale, to the 1600s. Ossegg stays in the forest collecting clues for many moons, and after long searching he finds the basis of the story: In an archive of the town Saxony-Anhalt lies the so called Wernigerode manuscript, which describes the 1647 trial against one Katharina Schradering, “The Baker Witch”. Hansel and Gretel weren’t children, but adults. Hans Metzler was himself a baker, and had accused Katharina of being a witch to cover up for him and his sister Grete murdering her. Ta-da, the saga becomes reality, just like in the case of Beowul

Fotograf: Raymond Hejdström, Gotlands Museum

Nora: How did the poem arrive in England?

Bo: My understanding is that Beowulf was composed mostly orally on Gotland and later transmitted to England by Swedes once they had gained control over Gotland. I propose that the poem was brought to England already around the year 600 and that it must have happened by direct transmission, not by some slow distribution. I imagine it happened in connection to some lordly marriage between a Swedish lord’s daughter and the young king Redwald of East Anglia and that this could all be indirectly illustrated by the peculiar Scandinavian ship graveyard at Sutton Hoo. Around this time they’d speak about the same language there as in eastern Sweden. The English must have initially understood Beowulf as a foreign, heathen poem, not seeing fit to insert their own tradition into the poem. Later on, it seems English bards reciting the poem put cheerful Christian slogans in the mouths of the poem’s heathen main characters Beowulf and King Roar, to hilariously contradictory effect.

Nora: You talk about mythical elements, in Beowulf the fire breathing flying snake would be one example. You’re saying that’s really a metaphor for the real world enemy that we know burned down Gotlandic villages like Torsburgen during this time. Does this mean Beowulf can be used as a historical document regarding kings, wars and living conditions in Scandinavia between the years 400 and 500? How should we view these old tales? Are they a kind of verifiable document for yourself as a researcher in archeology?

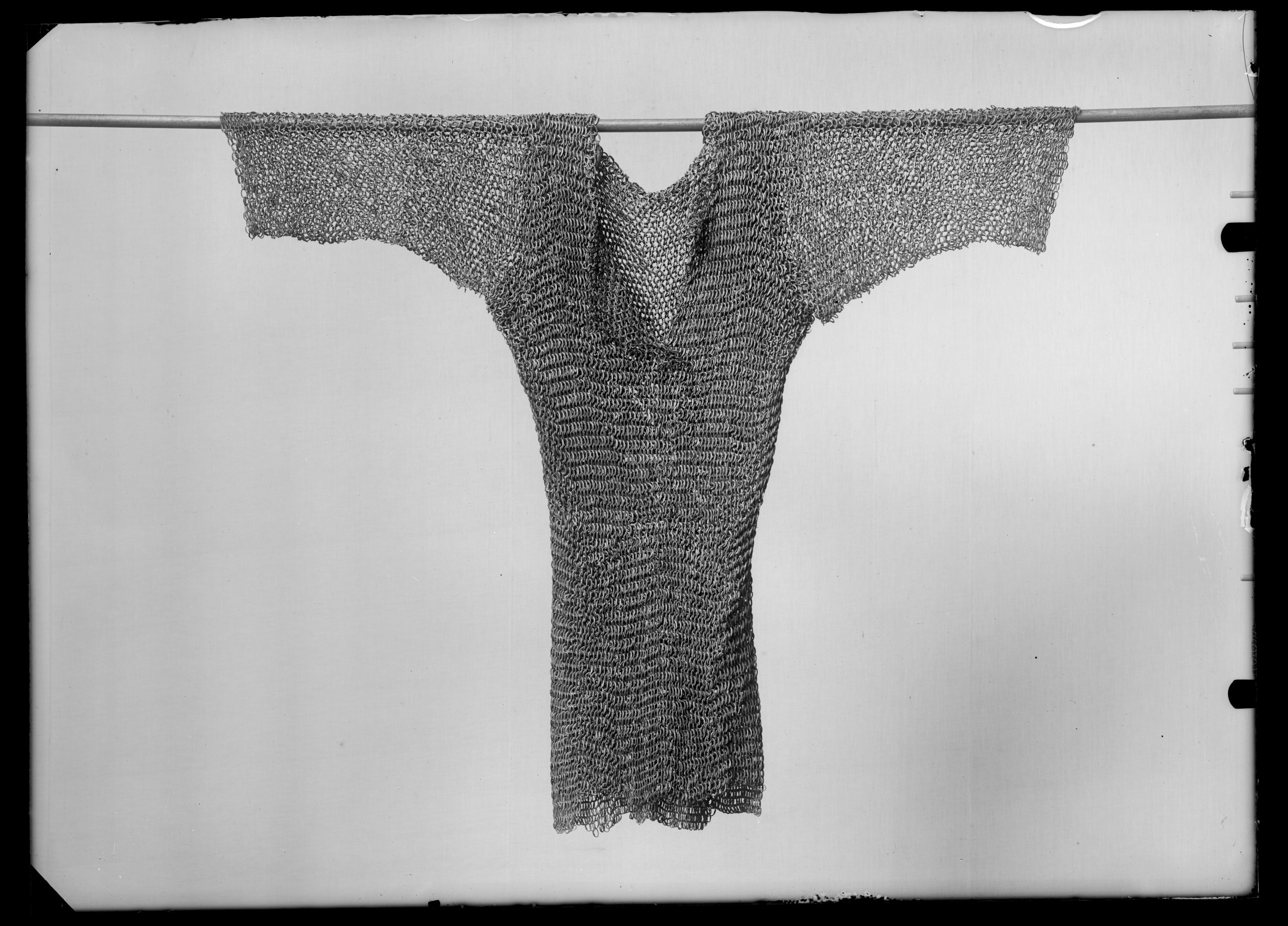

Bo: There are aspects of the poem that allow us to date it. Particularly, there’s an abundance of gold necklaces and arm rings. On every other page there’s mention of gold rings and expensive byrnie armour. There were plenty of golden rings in the Nordics between 200 and 550, but from the two centuries following 550 there’s not a single damn gold ring preserved from the entire Nordics. In England there are hardly any gold rings of that type for almost a thousand years. In other words, Beowulf is an enclosed time capsule from the time just before 550. An English author in the 700s wouldn’t have had the faintest idea about the material world being described and couldn’t have written the poem. But the fact that Beowulf isn’t fiction doesn’t make the poem a testimony of truth. It is, however, a historical source of remarkable quality for its time.

Beowulf is an enclosed time capsule from the time just before 550

Nora: How does one navigate between the real and made up aspects of historical tales when trying to use them as historical documents? What’s what, how do you know?

Bo: It’s no easy task, separating fiction from truth in old poems. The people of the past weren’t primitive but rather lived in a world where the common practice was to express oneself poetically through visual means. Lacking scientific reasoning, it would have been natural to apply supernatural explanations to the incomprehensible, using metaphors to explain that which felt frightening. During the Middle Ages, they didn’t shy away from depicting the Black Death as a personification of death, a ghastly skeleton reaping human victims with a sharp scythe. In the 500s they had similar ways of thinking. Many of the Icelandic sagas are family histories based on reality but they can still have fictitious additions. As magic was part of lived reality it’s only natural for it to show up in the poems. Oral stories from around the world are filled with supernatural events that might mirror reality. Are you familiar with Stonehenge?

Nora: Sure.

Except the story of the truth behind Hansel and Gretel held no truth at all. The book The Truth About Hansel and Gretel was written by the German humorist Hans Traxler. It was a so-called fictive nonfictional text that managed to fool academics as well as the press when it was published in 1963. West German magazine Abendzeitung called it “the book of the year, and maybe the century”. Much like Traxler’s protagonist Ossegg became obsessed by finding the witch’s house from the fairy tale Hansel and Gretel, the German archeologist Heinrich Schliemann spent large parts of his life in search of the city Troy, hoping to prove that Homer’s Iliad relates true historical events. Classical architecture found more solid scientific ground through Schliemann’s work, which in the 1870s aimed to explore the origin of the Greek civilisations of Troy and Mycenae. Whether Schliemann actually found Troy or not remains a somewhat controversial subject, but there are claims that the Hissarlik area in northwestern Turkey, near the Dardanelles, was indeed Troy. Until the end of the 19th century, tales of fiction were used by historians as reliable accounts of the past, and to this day, what texts remain from prehistoric times are being used by scientists to better understand what the humans of the time thought and felt. Many societies begin their historiography with myths and legends about their rulers and people.

the fact that Beowulf isn’t fiction doesn’t make the poem a testimony of truth

Bo: There’s a researcher who has spent twenty years looking for the origin of the large rocks used for building the mighty south English Stonehenge monument, dating to around 3300 BC. Now it seems they’ve found a place in Wales, to some extent through guidance from old Welsh oral so-called tales, that speak of a stolen stone monument. Most mythical tradition is likely to have some base in reality, which is then obscured through the passage of tradition, only to end up losing almost all connection to reality.

Nora: You’re saying that tales have become more metaphorical through time, but that they most often hold hidden truths to discover. Many people claim the Bible is truth, how do you feel about that? Pseudo-theoreticians will often use similar methods as the ones we’ve covered to point toward some bigger underlying truth.

Bo: Creationist concepts pop up here and there, unfortunately. Believing in democracy, justice and human rights is all fine and dandy, but in these times of stupefying change many are scrambling to believe in something. Humans are myth-loving creatures obsessed with magic, we love believing in that which can’t be proven to exist.

Nora: Where’s the truth in that?

Bo: Nowhere to be found. But all superstition, including religion, can be perceived as reality.

Nora: I also think of archaeological practice as a form of storytelling. I imagine finding this tiny object that unfolds into an entire story of times past.

In her book The Goddess Trilogy, archeologist Marija Gimbutas formulated what she saw as the differences in the ideological systems of old Europe and the Indo-European Bronze Age. Gimbutas saw the old world as centred around the goddess. These gynocentric societies were peaceful, honoured women and advocated for economic justice, according to Gimbutas. In the Bronze Age, these views were replaced by androcratic value systems, imported by the Kurgan people who invaded Europe, forcing upon it their hierarchic rule tailored around male warriors. To prove this, Gimbutas primarily pointed to the abundance of Venus figurines found in just about every excavated neolithic settlement or place of burial. These were employed to reconstruct these ancient people’s world view and value system. ”I do not believe as many archeologists of this generation seem to, that we shall never know the meaning of prehistoric art and religion. Yes, the scarcity of sources makes reconstruction difficult in most instances, but the religion of the early agricultural period of Europe and Anatolia is very richly documented. Tombs, temples, frescoes, reliefs, sculptures, figurines, pictorial painting, and other sources need to be analyzed from the point of view of ideology.”In The Chalice and the Blade from 1987, historian Riane Eisler traces the tension between these two ideological models – gynocentric and androcratic – referred to in her book as partnership or dominant social systems, from prehistoric times until today, partially based on Gimbuta’s research. Other archeologists question whether the great abundance of female figurines in these early cultures, dating back thirty thousand years or more, really means they revered a goddess or “The Great Mother”. Some dispute whether the figurines even depict females in the first place. Other archeologists criticise the idea that humans of the past would have been more peaceful, others still aim to bust the myth of humanity’s development from a barbarian state of being to a civilised one. Archeology can easily turn to mirroring what people want to see.

Courtesey of Livrustkammaren

Bo: Archaeology tries to retell past times, but the result is not seldom rather scanty, not something prehistoric humans would have enjoyed. Recent times have seen some improvements and things will continue to get better. We’re still just starting out.

Nora: How can a small object like an arrowhead tell us something about its entire surrounding world?

Bo: As an archaeologist, one rarely works with one object but rather with large quantities which can give us an overall picture. A single item won’t tell you much. You might find a spindle whorl and realise it belonged to a loom, but we won’t find out what the person doing the weaving was thinking about. There are limits to what an archaeologist can learn.

Nora: What is there to learn about the time before written language?

Bo: We know a whole lot, but not so much about people’s conceptual worlds. The little we do know about that aspect comes from antiquated poems like Beowulf. One interesting detail that has been unveiled by European burial findings is that the prehistoric concept of the soul is different from today’s, in the sense that the soul was considered to be bound to the body. After death, the soul would only be freed once the body had decomposed or been cremated. Today, according to Christian and Muslim as well as secular belief, the soul escapes along with the last breath. This is why archaeologists have found so many objects in prehistoric graves. These offerings were meant for the journey to the realm of the dead, where you would hope to arrive in fancy clothes, with jewellery, weapons and so on. With the arrival of Christian faith, a lot of that archaeological material vanishes.

Archaeologists researching prehistory face a tough task. They need to reconstruct the story of human history with as much detail as possible, relying on a limited set of clues, like artefacts and objects made and used by someone in the past. Those who study prehistory will most often employ abductive reasoning – it’s not about verifying as much as it is about finding the most likely explanation. But how do you know what the probable explanation for a phenomena is without understanding the conceptual world from which the phenomena stems? Accounts of the past often take the shape of tales. Historiography claims to report on actual courses of events, but which events make the cut is often determined by how well they fit into the narrative structures of historiography.

[Bo points to the cover of his book, showing a long rowing boat depicted on a Beowulf-era Gotlandic picture stone.]

Bo: This is a picture stone from Gotland which shows how a dead prince journeys to the land of the dead after having been cremated. Why would you be buried in a boat? Because when you’re at sea you can see how the horizon merges with the sky. One can easily assume sailing all the way to the horizon will lead you to the heavens. Those kinds of observations could be the reasoning behind the custom of ship burials, the idea being that the water you were rowing or sailing on eventually turned into air, elevating the ship to higher levels. Prehistory’s conceptual world is full of these kinds of metaphors that might come across as mystifying to us but that still, in their own way, always had a logical base in reality.

Nora: How can we surmise this from a picture like this one? How can we know what motivated people to get buried in boats, or whether or not this picture concerns a burial at all?

Bo: You can’t surmise that from any single image but rather from the collected archeological and historiographical source material at hand, not least that from the Vendel period and Viking age.

Nora: What does this picture have to do with Beowulf?

Bo: It’s from a Gotlandic gravestone dating back to Beowulf’s time. I’ve included it to demonstrate the high aesthetic level established in the Nordics around this time, easily at par with the rest of Europe. We’ve been raised with the misconception that prehistoric humans were nothing but unsophisticated thugs. That was not the case.

In the book A History of American Archaeology, the time between 1492 and 1840 is described as an era of American archaeology dedicated to pure speculation. The piles of artefacts at hand couldn’t be ignored, becoming subjects of wild guessing. Knowledge amassed virtually without any criticism and would almost magically point toward the resulting chronicles of truth. Granted, traces of this state of affairs remain in current archaeological research. It’s a given that history is being continually written from a point localised in current time. All historiography is impregnated by the contemporary. Thus the question isn’t whether one is influenced by the current day, but rather how and to what extent one is. One reason for archaeology becoming recognised as a standalone branch of science in the 1840s was its attractive force on people with strong nationalist interests, which in turn were intertwined with industrial capitalism. For these powers, archaeology became an ample tool for legitimation. Small objects unfold into history. Some claim that history goes through changes to fit into dominant ideology, but I wouldn’t go as far. Still, all storytelling is a product of the author’s imagination. Just like humans truly love uncovering truths within myths, historical truth is a myth in itself, a kind of creative mythologising about events that occurred, thoughts people had and the way things might have been once upon a time, long ago.

in these times of stupefying change many are scrambling to believe in something

Nora: What part did storytelling play in mankind’s early history?

Bo: It was incredibly important. Also, you’d remember virtually anything you were told. A single person could have hundreds of poems and tales at the top of their head. Many of the Edda poems preserved on Iceland during the Middle Ages are about events in the Nordics and on the European continent during the 200s, 300s and 400s, even if the contents have changed significantly along the journey. For the sake of memorisation, one would tell stories in a half-singing way, in a certain rhythm, using various forms of repetition. Lyrically, in other words. There was no TV, no phones, computers or films. So what would you do in the evenings or during winter?

Nora: You’d tell stories.

Bo: You’d tell stories! You’d sing stories. People have done that all over the world throughout the ages. The fact that all known primitive people on Earth have been found to have a tradition of oral, lyrical storytelling, indicates that the art of storytelling is as old as the brain of modern man, which had its current size, shape and structure already three hundred thousand years ago, meaning brains had the same intellectual and linguistic potential as today. All of this points to there having been an advanced storytelling tradition in the Nordics ever since the area was populated after the Ice Age, thousands of years before the Iron Age.

| Text | Nora Arrhenius Hagdahl |