between the self and the others, and the other as the self

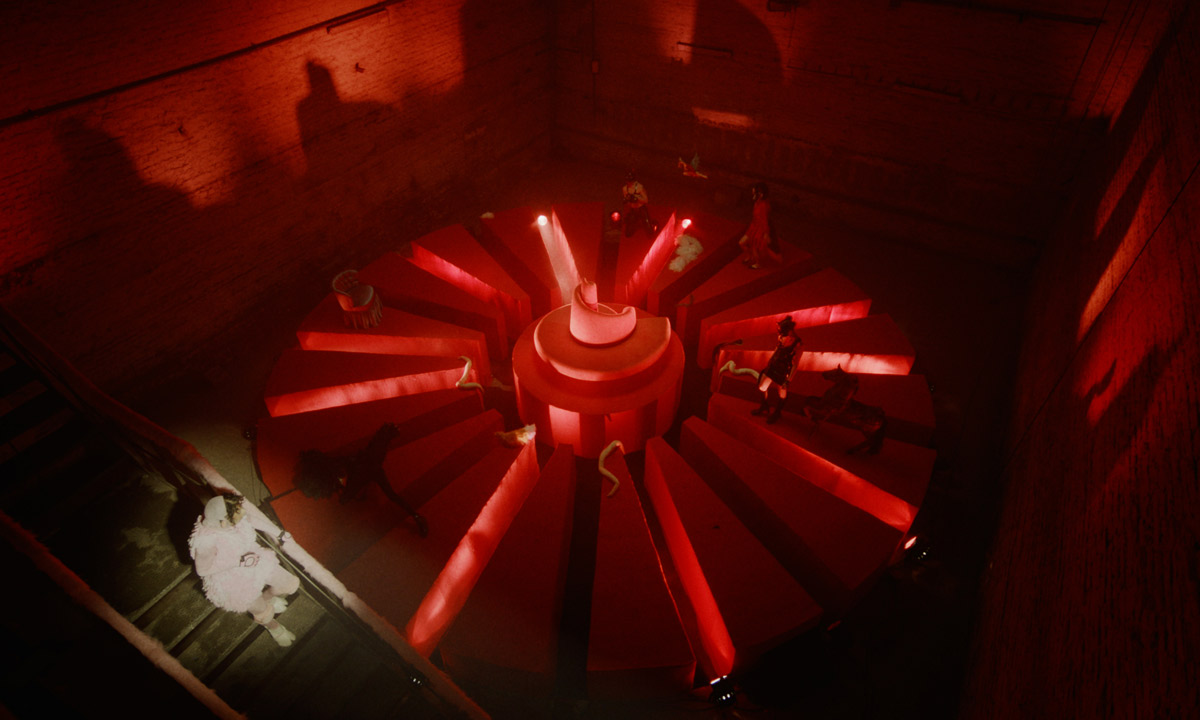

Entering Marianna Simnett’s world often feels like going down the rabbit hole – especially when you’ve just followed an oversized plush animal’s tail through a velvet curtain into the darkness, as was the case in the British-Croatian artist’s video installation The Severed Tail at the 2022 Venice Biennale. As you immerse yourself in the strange and compelling narratives that Simnett creates through combining fairy tale with fetish, desire with revulsion, and untamed thought with unexpected catharsis, the truly uncanny space you find yourself in is one where reality and fiction bleed into each other.

In conversation with curator and writer Linnéa Bake, Marianna Simnett reflects on the slippages between self and other, the real-life impact of creating one’s own worlds from scratch, and the liberating potential of facing, and celebrating, the monsters within oneself.

Linnéa Bake: The close relation between the dreamy-nightmarish universes you open up within your practice and the fairy tale as a narrative structure is an ongoing element in your films, performances and installations of the past years. There is this contrast between the perceived innocence and naivety of children’s stories, songs or rhymes that you employ and subvert in some of your works, and the dark and twisted quality of their contents. The fairy tale is traditionally a moralistic, sometimes gruesomely educational format, and your approach to storytelling, especially in relation to the fairy tale’s or the fable’s characteristics as moral tales, seems to speak to such conditionings of value systems. Is it fair to say that some of your works’ proximity to these forms of fantastical narration is a way of reclaiming and rewriting their sense of moral authority?

Marianna Simnett: I grew up with telling stories and fairy tales, coming up with characters with my dad, who would just ask me each night what I wanted tonight’s story to be about – in a way I would actually tell my own story to myself, as he would include all of the things I wanted in it, and then tell it back to me.

LB: Did you correct him, if he told it wrong?

MS: Yes, like a baby director! Even if I use a narrative form that is so much about moralistic endings, none of my works prescribe a way of being in the world. If anything, they offer a way out of rigidity and oppression. I hope they don’t preach or try to tell people how to be. They’re stories about people who feel strange within normative environments, they offer ways of coping with this position, and often my characters do that with a great sense of wildness and free-spiritedness, through fantasy and play. I think of this narrative strategy as a way of latching onto imagination and using it as a weapon against the environment that you’re caught within. This is important for every single work of mine – whatever medium I choose to work with, there is always a narrative.

In some earlier works of mine I used these intentionally catchy lyrics that would continue to ring in your head after you left the room. These types of songs can be very cruel things, you know. Take the nursery rhyme Ring a Ring o’ Roses, which is in fact about the plague. All of these lullabies historically have contained some of the darker fears of humanity, like the wolf at the door coming to ravage you at night. When dealing with trauma, abuse and violence, by demarcating it within a space of fiction, we are able to look at it and interrogate what’s happening without actually reinforcing the violence that’s going on in reality. You’re aware of being inside a kind of illusory space, you don’t actually believe that the rapist is there in the room you. The structure of a fairy tale doesn’t slip.

LB: Your practice has often been placed in the category of “fantastical realism”, combining fictional settings, scenarios and storylines with an at times almost clinical documentary aesthetic. An image that unites these aspects for me, and that continues to haunt me, is that of the Blue Roses from an earlier video work of yours of the same title (2015) – a shot of blue, grovelling protrusions on a leg, moving like worms under the human skin. Describing a medical phenomenon of varicose veins here, the blue rose (or more generally, blue flower) is at the same time a central symbol in Romanticism, standing in for desire, the metaphysical striving for the unreachable, and magic…

MS: The blue rose was really interesting to me in several ways, firstly having to do with the body, beauty and disgust, secondly having to do with a humanist perspective and domination over the natural world. You also just made me think of the blue fairy from Pinocchio – that figure of the guiding light, who tries to stop Pinocchio from getting into trouble, a good witch. The blue pigment in food and plant life is called delphinidin. It is a particular blue pigment that cannot be absorbed by the rose because this flower has too much acid in its chemical makeup. Scientists have tried to create a blue rose, but it has not been possible. So you get these dip-dyed, shitty versions that people sell.

I found out that there is a Japanese brand that came up with the first blue rose, and they called their creation “Applause” – patting themselves on the back, this human satisfaction with controlling nature was at the core. Same with the cockroaches that appear in the film: Forced into being something that they’re not, adorned and hybridised into this biological-technological creature, they represent a critique of what humans expect the world to be. The other aspect, on a much more personal note, was around matrilineal illness, specifically the illness in that film, which has to do with varicose veins: The first memory of me seeing my grandmother and my mother with what I thought were roses on their legs, these big bulbous veins. I remember getting told off, even hit once, for calling them “blue roses”. But I did not know that they were something that was supposed to be hidden – I thought that they were beautiful.

All of these lullabies historically have contained some of the darker fears of humanity, like the wolf at the door coming to ravage you at night

LB: In relation to this tension between the illusory space and the at times seemingly documentary character of your works, can you talk a bit about your choice to mostly work with non-actors? In your research process and during script writing you encounter individuals from various professions and backgrounds, and then you invite them to re-enact their own parts, which – perhaps due to the protagonists impersonating themselves – brings the fictional set up of your films unnervingly close to the “real” thing. In this context, I’m also curious to hear about your experience with LARPing [Live Action Role Playing] which, as I understand, was part of your method in developing the script for one of your most recent works, the three-channel video installation The Severed Tail (2022), which premiered last year at the Venice Biennale.

MS: I have always been interested in filmmakers for whom casting is not an afterthought but essential. I normally cast the characters before I write the script, and their identity becomes one of the core guiding principles of the project. The Severed Tail began with the idea to make a work about the lost link between our human selves and animal selves: all humans have a tail in the womb, an echo of the animal we once were, but we never get to see it, because it’s gone by the time we are born. I was thinking about what kind of communities actually do wear tails today, and who out there is performing as an animal in their daily lives. This led me to pup play communities in Berlin, who welcomed me in and talked to me about why they want to be dogs. I even dressed up as a dog myself.

Forced into being something that they’re not, adorned and hybridised into this biological-technological creature, they represent a critique of what humans expect the world to be

I often immerse myself into a community for my works and I always go alone. I go on these wild expeditions without knowing the outcome. In a way, I’m performing a role as a researcher-slash-director, but I’m also willing to other myself, to become an animal or whatever I need to be, in order to immerse myself in a group. It’s about this sense of crossing a threshold. So, I wouldn’t say that my interest lies so much in LARPing itself, but rather in the possibilities of how fictional spaces can lead to real-life outcomes; experimenting to see what a different world would look like, if we just played dress-up for a day, and then taking that thought to its furthest logical conclusion. I love that space of fantasy and role play where you need to have full conviction while you’re in character. Then you can really go places.

LB: I’m interested in what you said about crossing the threshold into these spaces. What does it imply, to take something back out with you, from within these communities beyond a threshold and into a public facing form?

MS: It’s really difficult, actually. For instance, I went to Albania to research so-called sworn virgins, a very small community of women who choose to become men in patriarchal societies. It was such a difficult topic to make work about, because it almost put me into the position of an ethnographer or an anthropologist, which I don’t want to be. I’m very conscious of someone else’s right to tell their own story. I always try to make sure that everyone involved has a voice and a part to play in telling their story – that it’s not just about me, stamping down my claim on who they are, but actually eliciting more of an improvised response from them if they choose to take part. There are also decisions that must be made along the way, where I have to remind myself that I am the one telling the story after all, and that it doesn’t all have to be factually correct. I’m inspired by real scenarios and real people, but I’m not making a documentary.

LB: For me, this speaks to a specific sense of ambiguity, which I see reflected in your practice and in the way you deconstruct predetermined dichotomies: Beauty coexists with disgust, victims turn into perpetrators, innocence meets cruelty, and fiction seeps into the realities that we can actually find out there. These are some of the most haunting moments for me as a viewer, when I no longer know what is scripted dialogue and what is real conversation, what is documentary and what is fiction.

MS: That’s great. I think that is actually something I’ve always tried to do, across all of my work, to synthesise ideas and genres together in a way that you don’t know where one ends and the other begins. Not just in film, it’s the same thing in my way of working with sound or even watercolours – there’s always this bleed. Actually, that’s a term they use in LARPing: The moment when your character slips into your real life is called “bleed”. I’m really interested in the very uncanny space that emerges from those slippages.

I’m also willing to other myself

LB: In The Severed Tail, the story of a piglet’s transformative descent into a dark world of fetish and play after having had her tail cut off, there is this shot in the beginning that shows footage of an actual pig having its tail cut. I would say that of all the nightmare-material types of things I’ve seen happening across your works, for me, this was the hardest one to endure. If you think about it, that’s kind of crazy, since this “tail docking”, an existing practice of cutting the tails off piglets shortly after they’re born, is one of those things that actually happens on a regular basis out there in the real world. As a viewer, you’re within this realm of the imaginary, like sleepwalking through one of these universes full of cruelty, revulsion and pain, which you have created, and then this particular shot is the one that disturbed me the most: the one that is actually representing a real event.

MS: And it’s only a one-second shot! I think that it’s all about living with these contradictions. It’s really difficult to not try and find the answers to everything, but to accept the contradictions of what sometimes are completely clashing feelings of existence that don’t seem to go together. It’s about really understanding knowledge as being led by feeling and not intellect. Art is the perfect navigation tool for me to be able to express things that are very uncomfortable and indescribable in words, but nevertheless real. I know they are, because I feel them. The really touching thing about making art is having others meet me in that place, actually being moved by the works and understanding them, even though I haven’t managed to put everything in perfect sentences.

LB: Also feeling them, in a quite physical sense, I would say.

MS: Also feeling them! That’s what’s most important. I don’t care about anything else, as long as people come in and encounter it. They don’t have to like it, that is totally fine. But I will always strive to make work that has that ability to get beyond the brain and into the senses.

LB: Your work has moved increasingly from film towards other forms, such as performance and sound, as well as sculptures and works on paper. OGRESS, your 2022 solo show at Société in Berlin, was my first encounter with these more object-based elements of your practice.

MS: I was schooled in a drama context, performance and music have been with me since my earliest memories. I’ve always wanted to give people the most electric experience possible, and I was somewhat underwhelmed by gallery spaces, which felt so static and sterile. I wanted to go beyond the white wall and the frame and the image – like, why doesn’t it move? Can’t someone just shake the walls? For years, I thought film was the best way to do this, but then I wanted to tackle my aversion to making art objects.

With OGRESS, it felt like the right time to subvert everyone’s expectations of myself as a “video artist.” This exhibition, and The Severed Tail, or even my film The Bird Game (2019), felt like stepping into a new aesthetic language that’s truer to who I am today. My desire became creating a world I want to inhabit – constructing it all the way from the details on a crown to the costumes and sets, filling giant watercolour sci-fi landscapes with centaurs and strange creatures; breaking down barriers, both in subject matter and medium, adding multiple layers of complexity to my practice. This is the language I wish to communicate with from now on.

LB: An integral part of this new language is the flute, no? I’m thinking both in terms of sound and texture, but also as an object and your body’s presence in relation to it, the flute almost like an extension of it. The exhibition focused on the ancient myth of the goddess Athena who undergoes personal horror as she invents the flute…

MS: I’ve played the flute since I was seven. When I came to Berlin I invested in a much higher quality flute, as I decided this would be my COVID lifeline. This happened in tandem with a kind of explosion of materiality and learning within my practice. It was like going back to school. I started teaching myself new things, I took a music production class, I massively scaled up and developed my watercolours. It was about becoming very, very industrious and studious with my practice. Through all this, the flute became a daily practice. Its emphasis on breath helped me to stay sane during the madness. During this time, I came across this story of Athena, how she created the first flute out of the bone of a deer. It interested me because it’s, again, a story of beauty and horror, disgust and revulsion. When Athena played the flute, she blew so hard that her face contorted and became all puffed out, then everybody laughed at her. So, she dismissed the flute, cursed the object that had turned her ugly and threw it away. I wanted to embrace the horror and this strange queer body that I felt she had, exaggerate it and dress up as this big puffy-cheeked Athena. Blue Moon (2022) is one of the central pieces in the show, a single-channel video composed of AI-generated imagery of myself shapeshifting into the goddess Athena.

I was somewhat underwhelmed by gallery spaces, which felt so static and sterile

LB: I was really touched by the way this narrative of self-disgust turns into a super strange beauty in that work. As you said yourself, this is somewhat of a recurring theme that you express in very different ways. There is this scene in The Severed Tail, where the piglet sees herself for the first time after the scarring event. She looks at herself in the mirror and seems to find comfort in her own image, despite her previous desperation, pain and shame. As a viewer, you feel sort of safe with her; you feel her being safe with herself. I was wondering about this idea of shame and relief within disfiguration. There is a recurring presence of especially female characters in your works undergoing some kind of transformation or deformation, incorporating an element of the alien other in their morphing bodies, or turning into some kind of hybrid or chimeric creature. Can you elaborate on the way you think about monstrosity, not just in the sense of being condemned as such by others, but also as a self-attributed narrative?

MS: I think it’s an exciting place to be, if you choose to be the monster. If you embrace everything that is wrong with you, then no one can really harm you. You already admit to wearing your inside on the outside in a way… I have always been attracted to these monstrous figures or misfits in society and to people who are supposed to be the offenders, like the evil characters in movies. They’re always my favourite ones because they’re a lot more identifiable.

Still, in the scene from The Severed Tail that you describe, eventually her reflection mocks her and turns on her. I think most of my stories have this sense of slippage between self and other: in the way one reckons with this monstrous, doubled image of oneself. It’s like a celebration of being raw and untamed. Having bad manners and not saying the right thing at the right time. I really like when you can sense someone isn’t performing. Even when someone is performing, I prefer to watch them in the gaps, when they think they’re not performing.

LB: Because it’s a moment in which one stops caring about how one is being perceived?

MS: Exactly. When you stop perceiving this external gaze on yourself. I don’t know who I am when I’m not making something. So, my own monster is my artist self – and my artist self is very cruel to my real self, because she always thinks that I should be making something. It’s like getting into a hall of mirrors between all of the different identities. Ironically, the whole reason I started playing the flute again was so that I would strengthen my identity of who I was when I wasn’t making work. It’s ridiculous that I failed in that respect, because I just ended up making an entire show about the flute! Now I’m working on a whole flute opera. So it’s all gone the other way. As an artist, it’s crucial to understand that you are not beholden to just being in this one role. Given how punishing the industry is and how much it demands of you as a body, it’s so important to carve out spaces – safe spaces, like the piglet finds for herself – that can allow you to flourish.

| Imagery | Marianna Simnett, The Severed Tail, three-channel video installation (video still). Courtesy the artist and Société, Berlin. |

| Text | Linnéa Bake |