The future of humanity, space tourism, and approaching an interplanetary economy

Published in Nuda:Beyond

Christer Fuglesang is the first and only Swedish Astronaut to have spent time in space. In 2006 he participated in the European Space Agency’s Celsius Mission where he conducted spacewalks for technical installations and repairs on the International Space Station. In 2009 he did his second mission in space and became the first non-American or Russian citizen to perform more than three spacewalks. Today he is Professor of Particle and Astroparticle Physics and director of the Royal Institute of Technology Space Center. In this conversation at the institute, he talks with Emma Engström, Doctor in Environmental Technology and researcher at the Institute of Future Studies about the future of humanity, space flight and space tourism, the settling of Mars and approaching an interplanetary economy.

Emma Engström: I’ve been thinking about different forms of exploration. On one hand, there’s exploration of ways to improve society, and on the other, an implicit human curiosity and responsibility to explore. Do you see what I mean? What are your thoughts on exploration?

Christer Fuglesang: There are two ways in which I think about exploration. My academic research is an exploration of how the universe is constructed. There I study particles from space to get another piece of the puzzle of how the universe is operating and how it is held together. Then, in manned spaceflight, we talk about a different kind of exploration; an exploration of space where we research how humans can learn to travel further away and exploit other celestial bodies. Whether we can find materials in asteroids which we need on Earth, if humans can learn to live in other places than Earth and find other planets to thrive on.

EE: When you were up there, did you experience any revelation, anything spiritual or some kind of humility for, well, this vastness?

CF: It becomes obvious that Earth doesn’t seem so big, and you can’t see any borders. That it’s beautiful. And compared to the inside of the space shuttle which is very vulnerable — we have to be very careful with our environment up there. We have very little time if something happens, we help each other across nations. As an analogy for Earth, here we also need to care for our living environment and help each other do so. And when you’re there, looking down on Earth, you’ll speculate. How usual is life in space? How far is the closest civilization?

EE: I’ve been thinking of the story Aniara, which tells the narrative of being forced to escape a destroyed Earth. Aniara keeps traveling, but in the wrong direction, and that narrative makes me think about the fear I have for space. All of the things that we take for granted on Earth such as smells, sounds or people are simply not there. I’m wondering how you think about that, being so vulnerable when you’re in space.

CF: Of course, you don’t have a lot of the things that exist on Earth when you’re in Space. There’s no force of gravity when you’re in orbit which is both troublesome and fun. I think there are few people who want to live anywhere else then on Earth — I’d rather live on Earth than in space or on Mars for an extended period of time. But the sensation of trying something new, seeing new views of Earth, that’s an amazing experience. Also, we can improve our lives on Earth through the knowledge we get from that exploration. We want to learn to live on Mars because it expands the possibilities of humanity. We have an enormous challenge ahead of us and a lot of problems to handle, and we need to explore all potential solutions.

Earth doesn’t seem so big, and you can’t see any borders

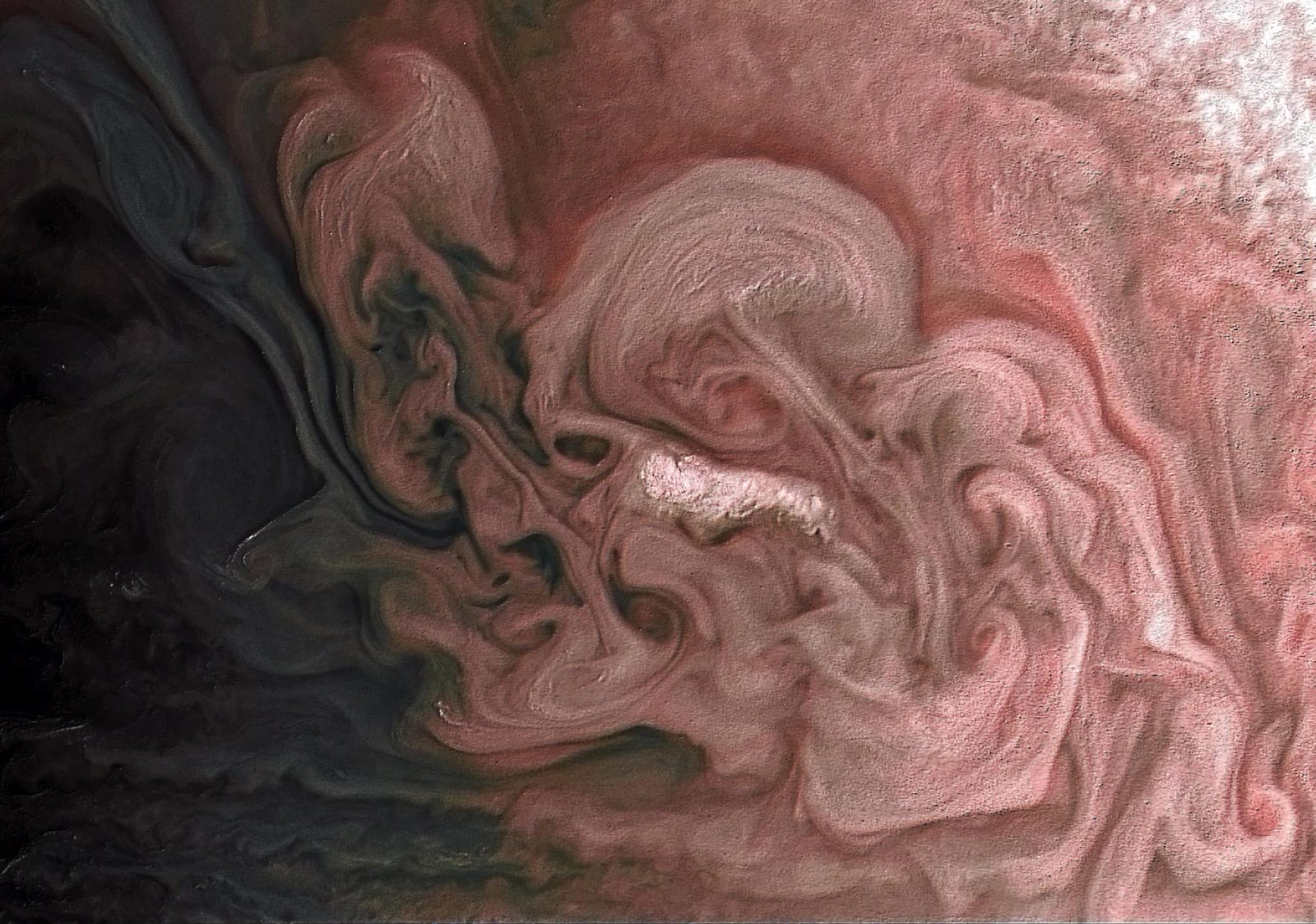

EE: What fascinates you the most about the universe?

CF: One thing is how much we humans have been able to understand about the universe with only the things we’re able to do on this tiny spot we’ve been on. And then it’s fascinating that anything exists at all. Something I see which many have a hard time with is accepting not knowing something. That’s the kind of thing which leads to a lot of trouble. People always have to find explanations or get worried or afraid, because something can’t be understood. We have to learn to accept that there are some things we simply can’t explain right now.

EE: I have a quote with me from the German film director Werner Herzog. During an Apollo mission, the crew left a camera on the moon which slowly traveled in a line across the surface for several days. He said, “I yearned to grab the damn thing.” He suggests that there should be a poet rather than an astronaut on the Moon. I’d be the first volunteer and I’d gladly go on a one-way mission to somehow tell that story. Is this something you think about when you’re in space, that you’re also a storyteller for the rest of us?

CF: You’re not the first to suggest that authors, poets, and artists should travel to space to better narrate what happens there. That’s nothing new. But for example, Alexei Leonov, the first man to do a spacewalk, for example, was an excellent artist who painted what he had experienced there. We’re not trained to mediate it in text, but we definitely get training in being ambassadors. We get a lot of training in video and photography in order to take as good pictures as we can. Maybe it’s only a matter of time before someone starts sending poets, journalists, and authors, but I think some astronauts have been very adept at explaining what space is like.

We have to learn to accept that there are some things we simply can’t explain

EE: I have a question regarding inherent indeterminacy. The idea that the universe is not deterministic, that we have free will. There’s some kind of fundamental physical chance with particles which I find as a source of consolation in that not everything is predetermined. What are your thoughts about that as a particle physicist?

CF: Scientists have had varying models regarding whether the universe is deterministic or not over the years. Einstein famously thought that there can be no indeterminacy, but rather that the universe had to be deterministic, that time and space followed a set course. But now quantum mechanics suggest that fundamental indeterminacy is real, implying that chance or randomness affects outcome. All results we have from research today point toward that the fundamentals of quantum mechanics are correct and that there is an indeterminacy that occurs across time and space. Personally I don’t think the question matters as most systems we have can more or less be described with indeterminacy. Almost everyone has a factor of chaos in them. Minimal differences in points of departure end up with very different end results, so even if it is deterministic, we can’t calculate it. In practice, it doesn’t matter.

EE: I see your point, but how do you think that the knowledge of processes such as chaos, wave mechanics or inherent indeterminacy affect our understanding of free will? Isn’t that something worth considering in the larger existential picture?

CF: No. Either it ends with heat death or it all returns to the big bang or it simply ebbs out to some sort of eternal steady state. These are entirely philosophical questions as regardless of how many generations we can conceive of will none ever experience any of these changes. I see it as completely unnecessary questions to concern myself with. It’s not something which affects how we live, so I find it wasteful for people to feel worried about it all ending up one way or the other when it doesn’t matter. Then you might as well start by worrying about the Sun consuming Earth in a few million years, which is closer in time and will happen for sure. We don’t have to worry about things which maybe could be a problem in a couple of hundred million years. That’s wasted energy to me.

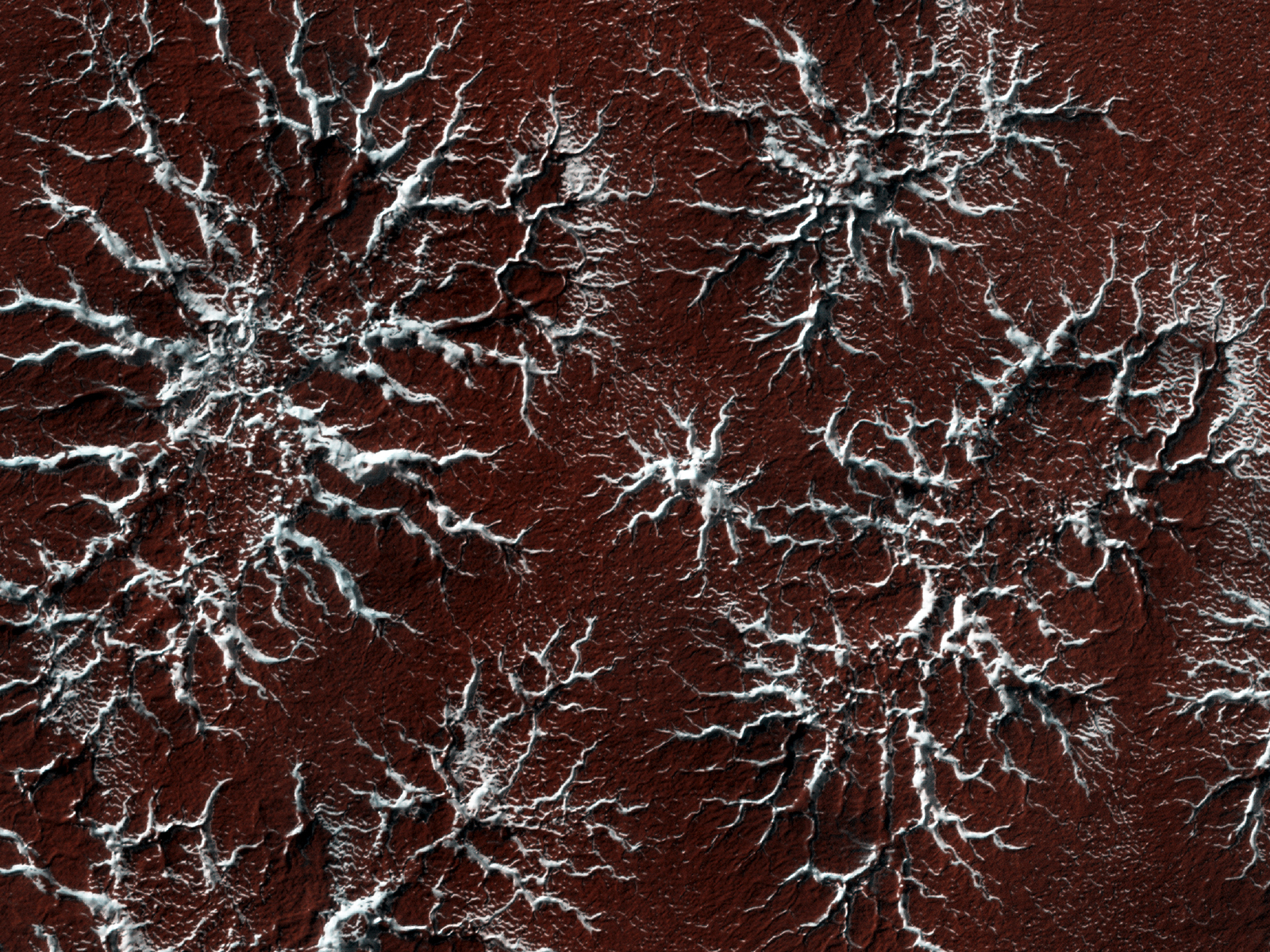

Japan ASTER Science Team

EE: Don’t you think that there are people who find space travel to be wasted energy?

CF: Maybe people might feel so. But space travel has the potential to help us on Earth within the foreseeable future, whereas heat death won’t happen for a long time.

EE: So you mean that we travel to space to help those on Earth?

CF: Partially. And its partially in the nature of our human curiosity to try to do those things. By that, I don’t mean that we’re not curious in trying to find out if there will be heat death or not or if there’ll be a new big bang. But you don’t need to worry about it. We want to know, yes, but they’re two different things.

Maybe it’s only a matter of time before someone starts sending poets, journalists, and authors

EE: There are many who think about what it’s like on Mars who might not have to worry about that.

CF: I don’t worry about that either.

EE: But it’s something which is heavily invested in.

CF: Because it has practical potentials.

EE: What are those potentials?

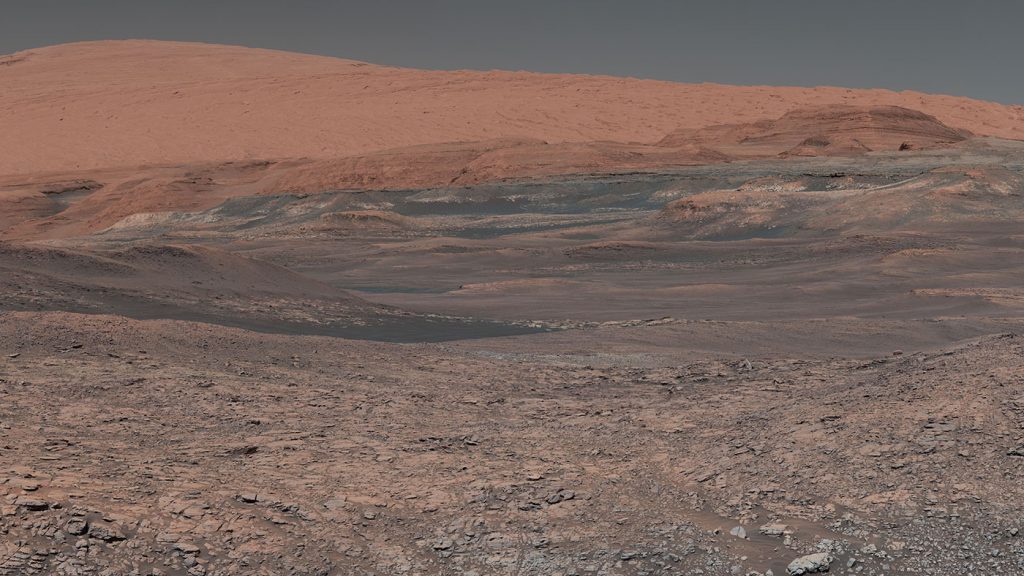

CF: Of Mars? Well, that people will be able to live there as well in the future. We can extract resources which could further the potentials of an interplanetary economy. If people start to live there, we’ll be able to produce things cheaper in a way which we can’t on Earth. Settling Mars will expand the potentials of humanity to travel even further into space and settle more places. Think of it like this, most of the time we either further progress and move forward, or we stagnate and finally, we regress. For humanity, progress lies in space.

EE: How likely do you believe it to be that we travel to Mars in the next hundred years?

CF: Very likely. What I see as the most likely scenario is that in about fifteen years, the first manned vessels will travel to Mars, and eventually we’ll build some sort of base there which will be permanently crewed. Eventually, people will actually want to settle there. Think about America as an allegory. When Columbus in 1492, let’s say rediscovered the continent, the Americas became known to Europeans. Then in practice, it took some 150 years before there was an actual surge of Europeans who settled the continent.

EE: It was about fifty years ago since we were on the Moon, and you’re saying we’ll travel to Mars within fifteen. But it was so very long ago we were on the Moon, how do these go together?

CF: It’s to do with incentives, why we do things. The reason we were on the Moon as early as we were was because of an enormous incentive during the Cold War. The USA felt that they had to prove to themselves and the world that they could beat the Soviet Union who had taken the first steps in space technology and actually were ahead in development. They were scared half to death when they began work on Sputnik, because if the USSR could send a satellite into orbit, what couldn’t they achieve? So they set a target which was so difficult to reach that they would surpass the Russians and were willing to submit almost infinite resources into it. The goal was reached, after which they realized that it was expensive and unsustainable. After that, things have slowed down. Recently, there’s been some competition again. China is clearly about to enter space and they are going to the Moon, and the USA again feel that they have to show that they are back in the race. Trump says 2024, but I find that doubtful. But the Americans have also said that the goal is Mars, which in part is to prove that they’re still ahead, but also because technology has caught up. Now we can build things which make it cheaper to travel into space. It’s not just nation-states anymore, but private companies such as Elon Musk’s SpaceX and Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin who also build rockets with the explicit intention to go to Mars.

EE: So you think that travel to Mars within fifteen years is reasonable when it was fifty since we were on the Moon? That just seems like such a fantastic number.

CF: We haven’t been standing still for fifty years, we’ve made a lot of developments. It’s only a question of resources. From not having had a single human in space to landing a person on the Moon and bringing them back alive in eight years. Because they had the incentive to spend those resources. That’s a larger step than going from where we are today to Mars.

EE: So, you believe someone will spend the resources needed on that?

CF: Yes.

It’s not just nation-states anymore, but private companies

EE: What are your thoughts on space tourism, to be able to soon buy a ticket into space?

CF: It’s only a matter of time before space tourism happens at a larger scale. Seven people have already paid for themselves to travel into space and spend time there. One person found it so interesting that he did it twice and paid roughly 20 or 30 million dollars to do so. But mass tourism will be different. First, we’ll see flights going above a hundred kilometers, as that’s technically the definition of space. But then you’ll go straight back so that you’re only in space for a couple of minutes. Just enough to experience weightlessness and to see Earth from outside. It’ll be quite some time before we have some sort of space hotel. But it will happen — there are several companies planning and developing both of those things.

EE: So if you want a good motivation to get rich, this is it?

CF: It’s probably easier to get into space by becoming really wealthy and buying something like this than getting any of the astronaut positions out there. But there will be a third option. Until now, all astronauts have been employed by governments and space institutions. Soon there will be private companies sending manned vessels into space and those will need to employ people. There will be new jobs for tourism when space hotels become a thing, which will need people working there and taking care of the arriving tourists. We’re moving to be part of a strong interplanetary economy.

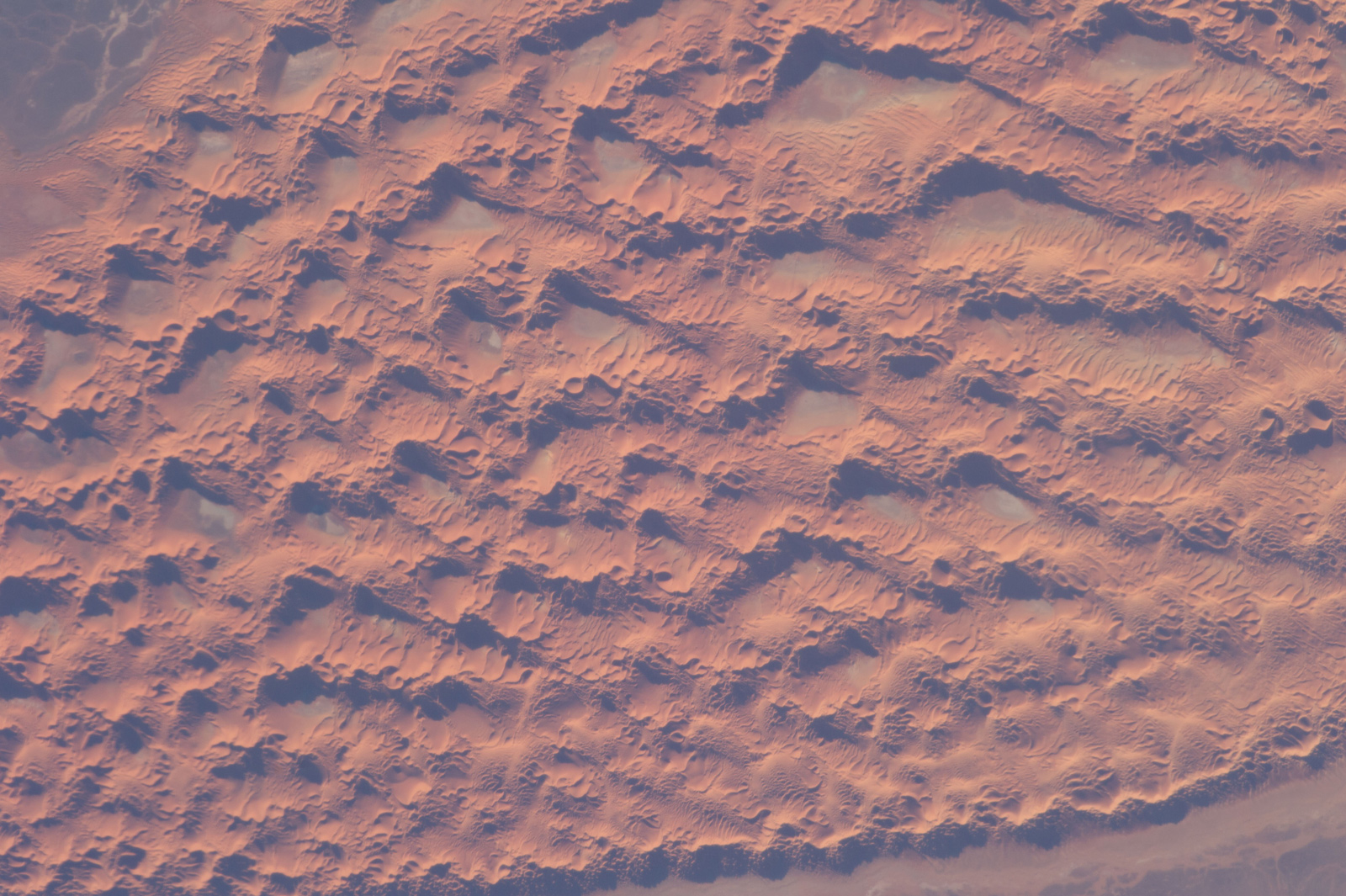

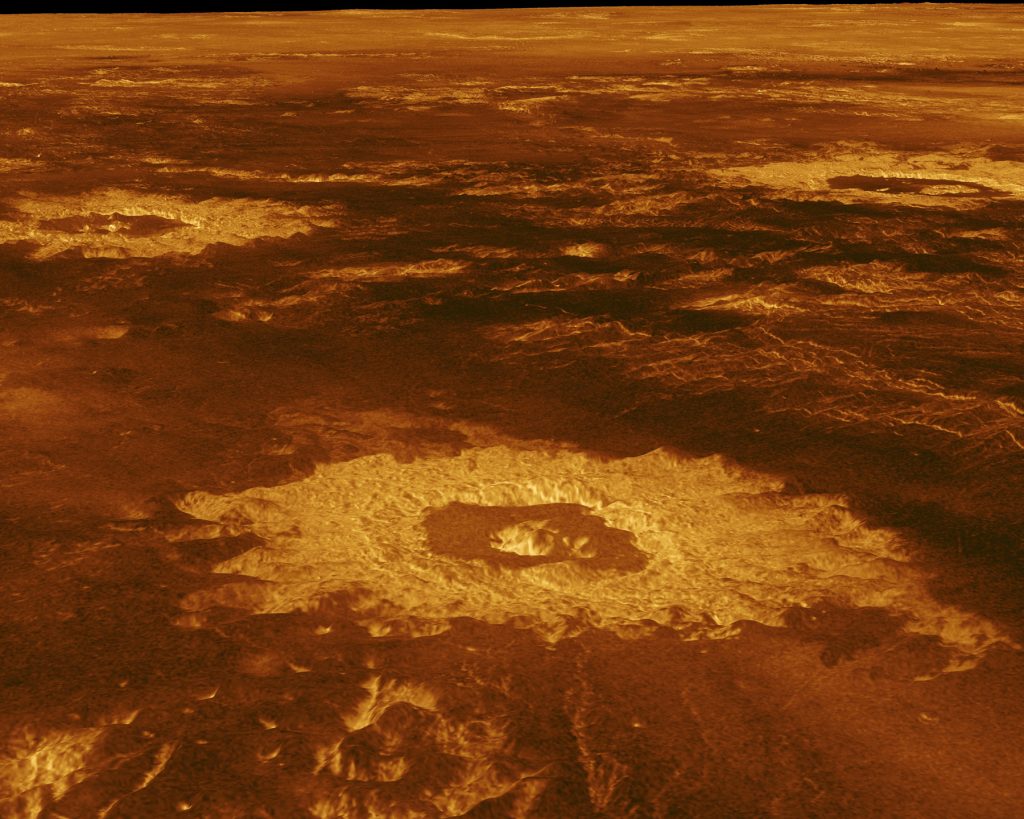

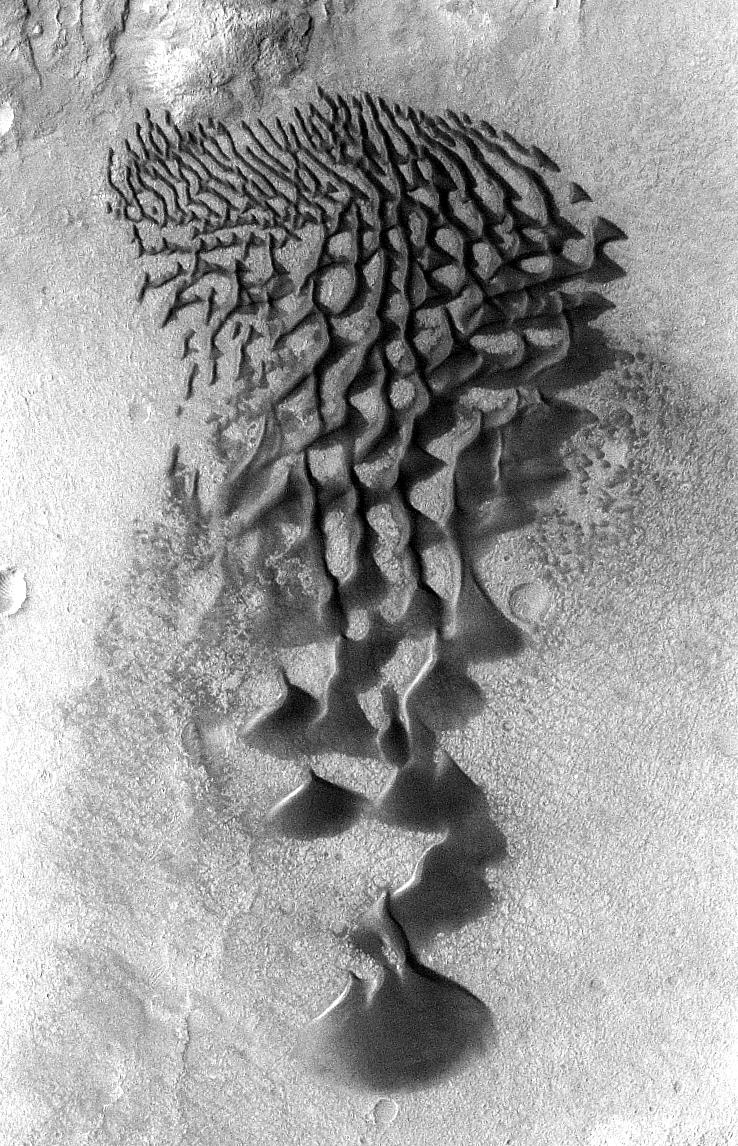

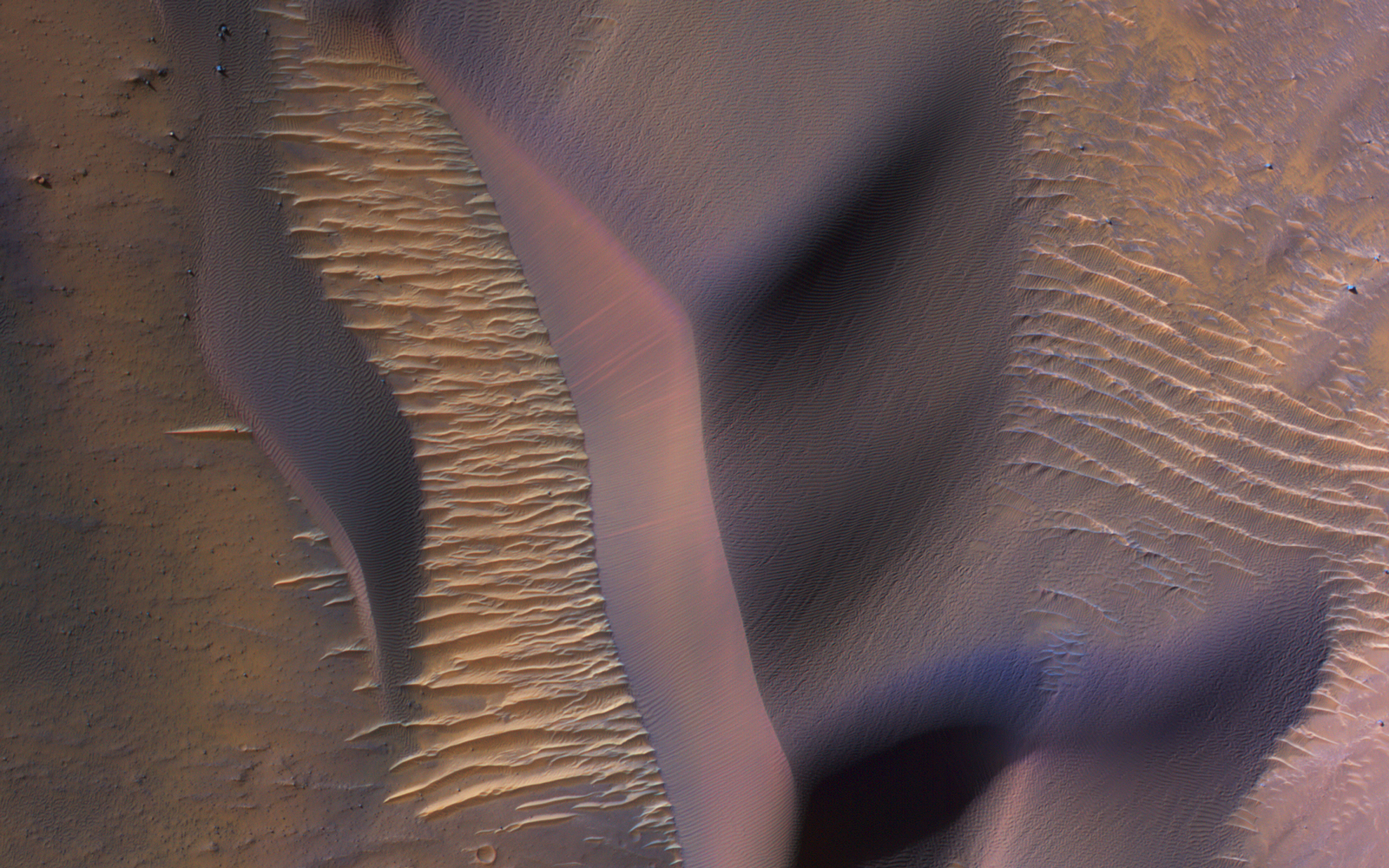

| Photography | NASA |

| Words | Emma Engström |