The director/electropop singer/YouTube weatherman

Few electropop singers are as misunderstood as David Lynch. Apologies, I meant to say few furniture designers are as polarising. Okay, few YouTube weathermen, whatever. You choose. If an eyebrow or two is raised in objection, it is because Lynch’s reputation as a leading American filmmaker has overshadowed most of his other artistic endeavours. Which is a shame – after all, Lynch is truly a Renaissance man, or should we say a Redécès man, given the lack of birth and surplus of death in his works. For what it’s worth, I support all of his hustles, with the exception of lamp design. Plunge me into the horrifying breakdown of reality and meaning, but don’t force me to purchase it for my living room, please.

It is, however, only fair that Lynch is best known for his work in filmmaking. While training to become a painter at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts in 1967, Lynch decided he wanted to make his paintings move and so he started making, you know, moving pictures. Most of his films – and Twin Peaks, of course – have become icons of Americana, aptly conveying the contradiction of that bizarre country: the glamour and the danger, seduction and threat, co-existing, or, more accurately, feeding off each other.

The themes in his stories are driven by strong yet diffused emotions – angst, desire, curiosity – that often evolves into an ultimately failed quest for meaning (and that’s the best case scenario). Lynch seems preoccupied with the ways we manage to turn a blind eye and trick our minds in order to not face the absolute truth of senselessness. If you watch carefully, amidst the dread and atrocity and sensory overload, concerned David is shaking his friendly finger at you, calling you out on your bullshit.

The locations for his films often epitomise these predilections; superficiality plays no mean part in the suburban idyll or the allure of Hollyweird. Violence has always been not a bug but a feature of these systems and the “bad guys” remain as elusive as they are in reality. For me and, I imagine, many other non-Americans, Hollywood and suburbia exist as eerie fairytale settings – familiar from overconsumption of media, yet, not real. Surely such artificial, haunting settlements could not really exist and be inhabited by healthy populaces? Lynch draws out the violent sickness behind the facade along with the dreamlike qualities of these places – and by dreams, I mean nightmares.

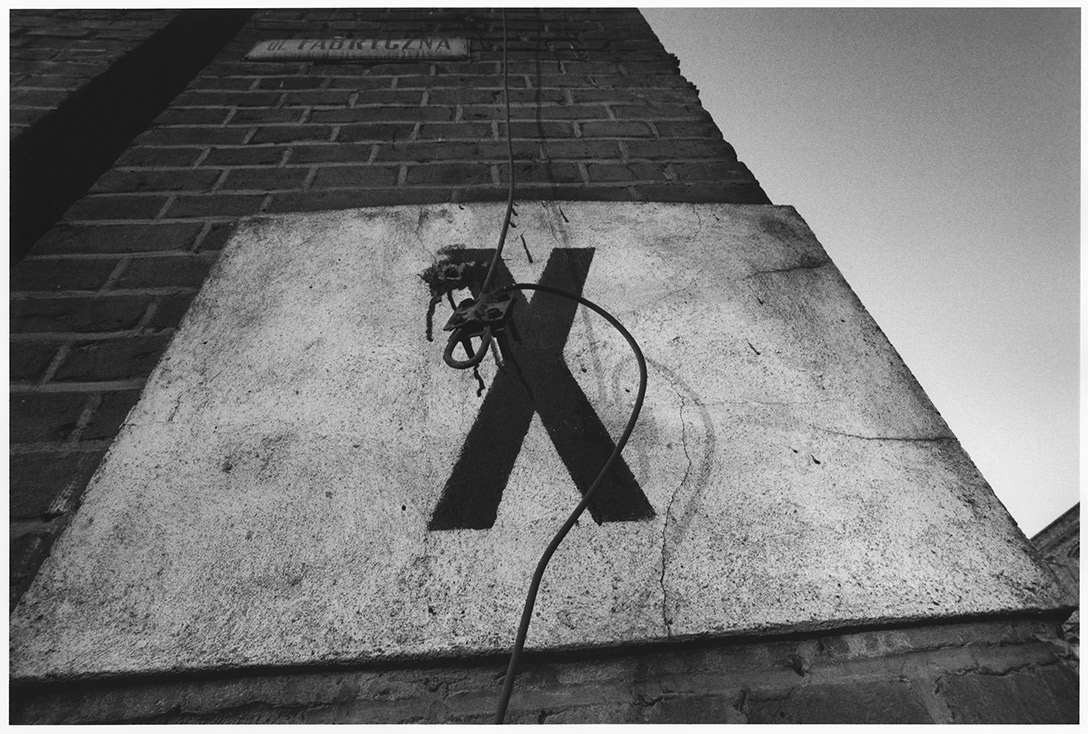

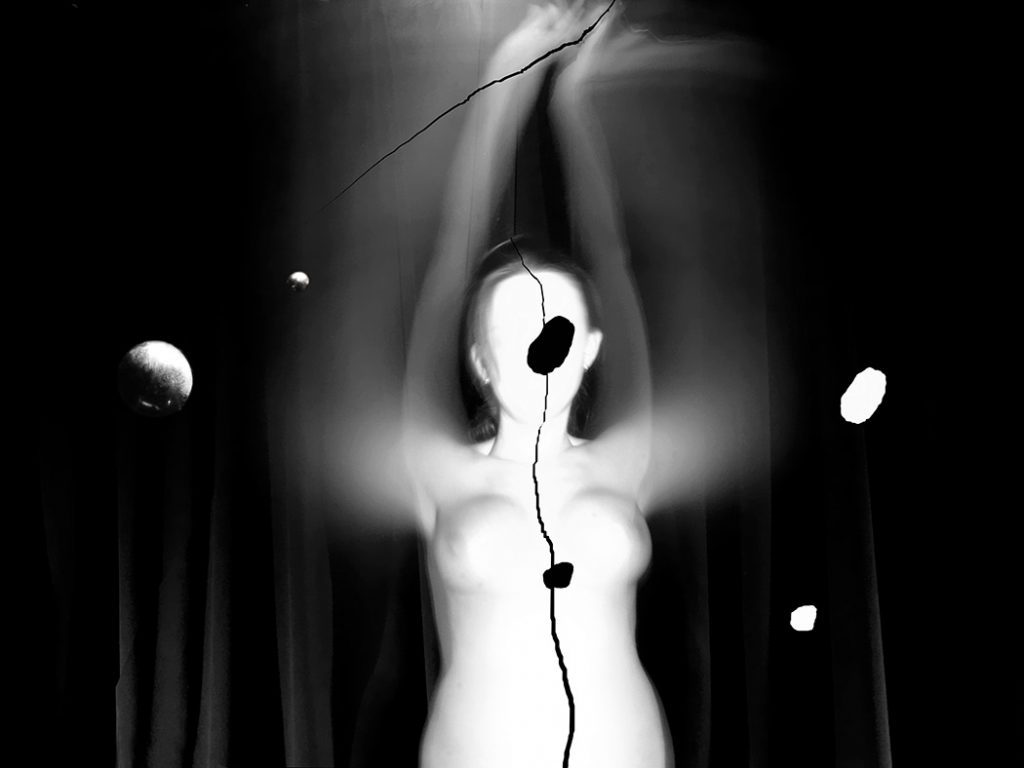

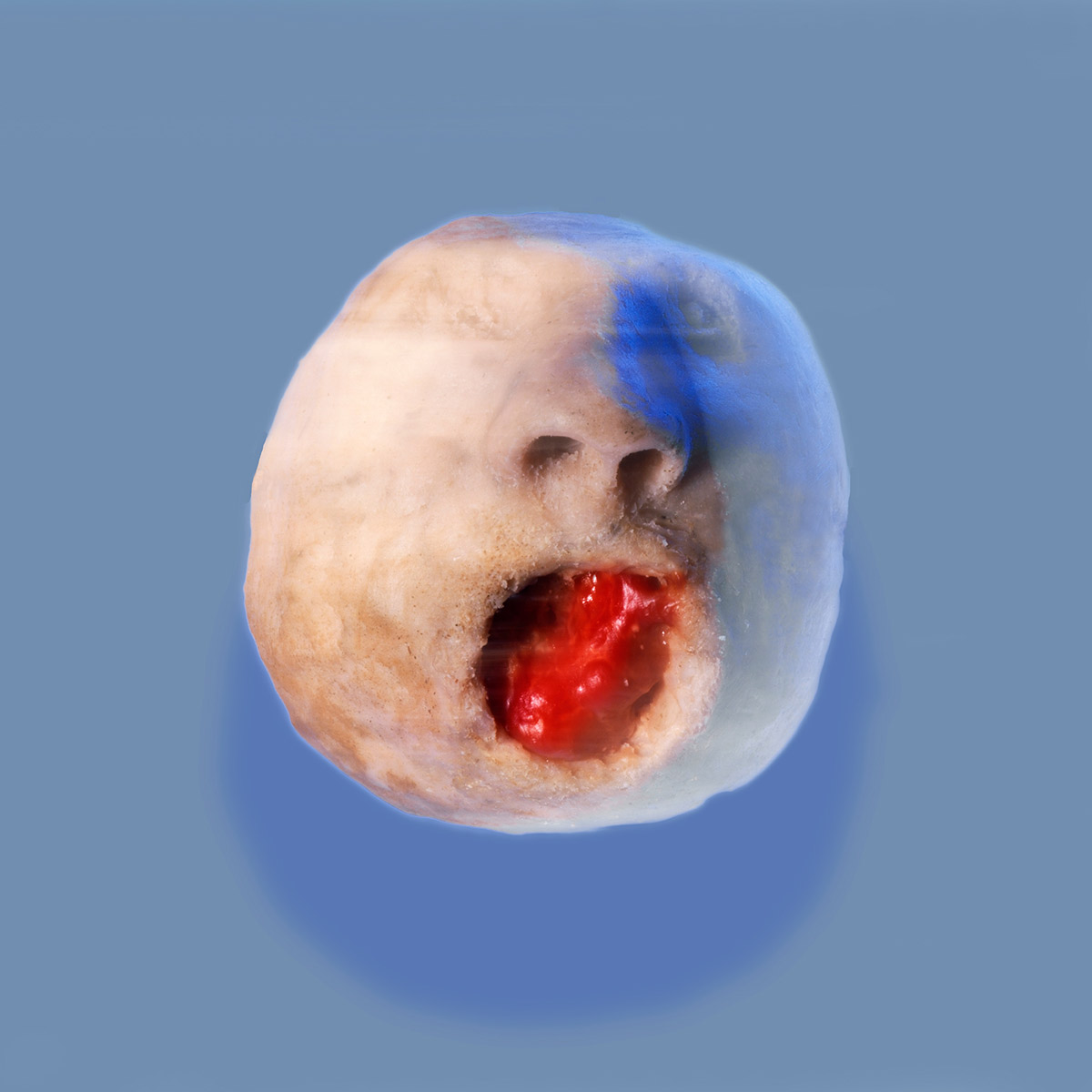

David Lynch, Untitled, Courtesy Helsinki Photo Festival

In all of Lynch’s iconic thrillers, mystery presents itself with an all-consuming feeling of disruption, usually through violence or a vague threat thereof (e.g. Blue Velvet, Twin Peaks, Inland Empire). While characters in his films quest to make sense of this disruption in order to prevent the threat from escalating, and something – a little murder or a bit of a collapse of space-time continuum – climaxing in some ominous way, this pervasive sense of threat manufactures an expectation of conspiracy. There is no “Lynchian” without the mystery, the threat, the anticipation of a conspiracy being uncovered, a threat exorcised, and safety and prosperity restored. But “Lynchian” also means no such happy ending.

concerned David is shaking his friendly finger at you, calling you out on your bullshit

Lynch knows us, weak and gullible beings that we are: We yearn to make sense where there is none, find patterns that will build a meaningful narrative, soothe our suspicion that fatalism might be a hoax. Though conspiracy has been a major feature in how we define ourselves through the ages – seeking to establish not only order but also our position in relation to the senselessness and confusion – in today’s annoyingly complex world we’ve reached a stage of such proliferation of conspiracy theories that it becomes impossible to look up anything online without running into something unhinged. All this meaning-making would be endearing if it weren’t so damn dangerous, conspiracy often slipping into its final product, extremism. We are all prone to speculation to some extent – Lynch knows that and uses this knowledge to tantalise us for his pleasure (take the legendary phrase in Twin Peaks that still intrigues and frustrates me: “The owls are not what they seem.”)

We, the audience, readily identify with Lynch’s protagonists and take their confusion and terror for granted; we want to be the heroes that will put the puzzle pieces together and save the day, with a bonus of saving the damsel. The catch is that although the characters might have legitimate cause for fear, they are often unreliable narrators to themselves and, in turn, to us (e.g. Fred in Lost Highway, Betty in Mulholland Drive). We’re so eager to position ourselves as the good guys that we’ll distort the evidence, forcibly moulding it to fit our story, and demonise others to keep ourselves on the right side, the side of purity. We’ve all done this before – in psychoanalysis, it’s called a dick move, or generating abjection.

Shamefully briefly, according to Julia Kristeva in her seminal work Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, the abject is something, or someone, that is cast-off by us so we can identify ourselves against it, having no relation to it. For example, a corpse is something familiar but in no way related to our continuing existence. The abject threatens us and our integrity, it “disturbs identity, system, and order.” Abjection is a visceral response, a gag reflex, the clutching of pearls. A significant segment of society has this response to Lynch’s work; it’s a pretty reasonable reaction to being confronted with a breakdown of meaning. I refuse his lamp designs so I can hold onto my stable, if illusory, conception of reality and what is permitted in it.

The abject “does not respect borders, positions, rules” and therefore must be rejected to maintain clear boundaries between self and all else. How can I cling to my exclusive, righteous identity if I follow the adage “Homo sum: humani nihil a me alienum plato” (“I am human: nothing human is alien to me”) and do not attempt to distance myself from whoever is scorned? If I, instead, see myself as no more or less capable of evil acts as the next bloke in the death row, then I resist the mechanism that causes abjection to people and dehumanises them. Only such righteousness doesn’t exist—the meaning of my own integrity would suffer too greatly, therefore, according to Kristeva, I must exorcise whatever threatens meaning. These mental gymnastics are a popular motif in Lynch’s filmography. The themes in his stories are often about the encounter with the abject, but they also correspond to the visual choices in his film work and photography which cause us to confront that which refuses boundaries.

All this meaning-making would be endearing if it weren’t so damn dangerous

In Lynch’s photographs, all of the bleached human-ish forms – some terrifying, some confusingly sexy – are abject. They make me nauseous because, though they resemble me, I find them threatening, undecipherable. They erase the border between being and something… already past it, something I’d rather not experience. The figures are going through a sort of metamorphosis – it can’t be a pleasant one, as the mouths in many of his photographs are contorted in agony. The blinding whiteness of skin, this absence of texture of the photographed bodies flaunts the sensation of death, and what is afforded texture – a rug, the, hmmm, seductive human egg? – feels soiled and foul.

More than “just” death, the light scorching these figures also showcases total erasure of identifiable personal features. A chalk-white body gracefully flails its arms while being split in two. A digitally munched-on torso with a deformed face whips out a friendly advice – SLEEP (I think this might encapsulate Lynch’s idea of comedy.) A woman screams behind glass, her outstretched palm banging on it, leaving greasy traces. None of these figures possess eyes, and only sometimes a gaping mouth. These bodies are empty, but not uninhabited, creating a sense of “almost humanity”.

All that but with one exception – an extreme close-up of a glamorous model showcasing how her nail polish perfectly suits her lipstick. At first, the portrait bathed in warm hues seems a truly odd subject for Lynch, if only on the surface. Glamour is its own metamorphosis into superficiality, a selling point for nothingness. This woman is no more an individual than the contorted shapes – a symbol, vacant. She is selling you something: the idea of glamour, that coveted wish of an urban fairytale, a deceptive idea with an absence behind it, a hollow dream.

Purchasable allure cannot substitute personality, but it can objectify – especially women. All of these female figures are dehumanised in their own special way, and float in their eerie universes as symbols of abjection. I’m not convinced that Lynch is making a feminist point through these tortured mannequins, but it tickles my pickle how these images could be interpreted in this or any other possible way, as they refuse straightforward explanation.

What can be certain is that Lynch cannot fail in making anything feel abjected. Even the snowman outside a quaint suburban house is abject, a familiar token of an idyllic childhood now left to decay, frightening us with a jolly memento mori. Even the granularity of Lynch’s film photography itself lets us bask in the dirty texture of melting snow. Abandoned industrial settings – a Lynch favourite – are also abject, like in the photo taken in Lodz, Poland – liminal spaces that have ceased to inhabit their purpose and now possess no meaning. No wedding photoshoot backdrop exactly. Already in Eraserhead, his feature debut, the industrial outskirts of Philadelphia married abject settings with the encounter with the abject as the theme of the film. The setting, the photography, the stories themselves all confront us with erasure of a legible world.

Nothing destabilises good old reality like an exhibition by Lynch, or an encounter with one of his films or lamps. He exploits our uncontrollable pursuit of fantasy in order to cling to meaning in reality, he upsets our storytelling expectations by refusing resolution and restoration of order. He knows very well our determination to separate ourselves from the illegible – what causes queasiness, what makes us question our position in this totally sensible world. You may choose to believe in whatever version of events you find soothing, Lynch muses, but sooner or later your demons will catch up with you. Perhaps startlingly, for me Lynch is one of the most realistic and ethical American artists working today.

| Text | Gabrielė Liepa |

| Imageries | Infinite Deep at Helsinki Photo Festival, 4th November 2022 – 28th February 2023. The exhibition was organised and curated by Christian Nørgaard |