in conversation with Klara Zetterholm

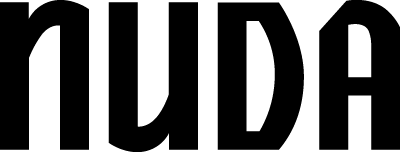

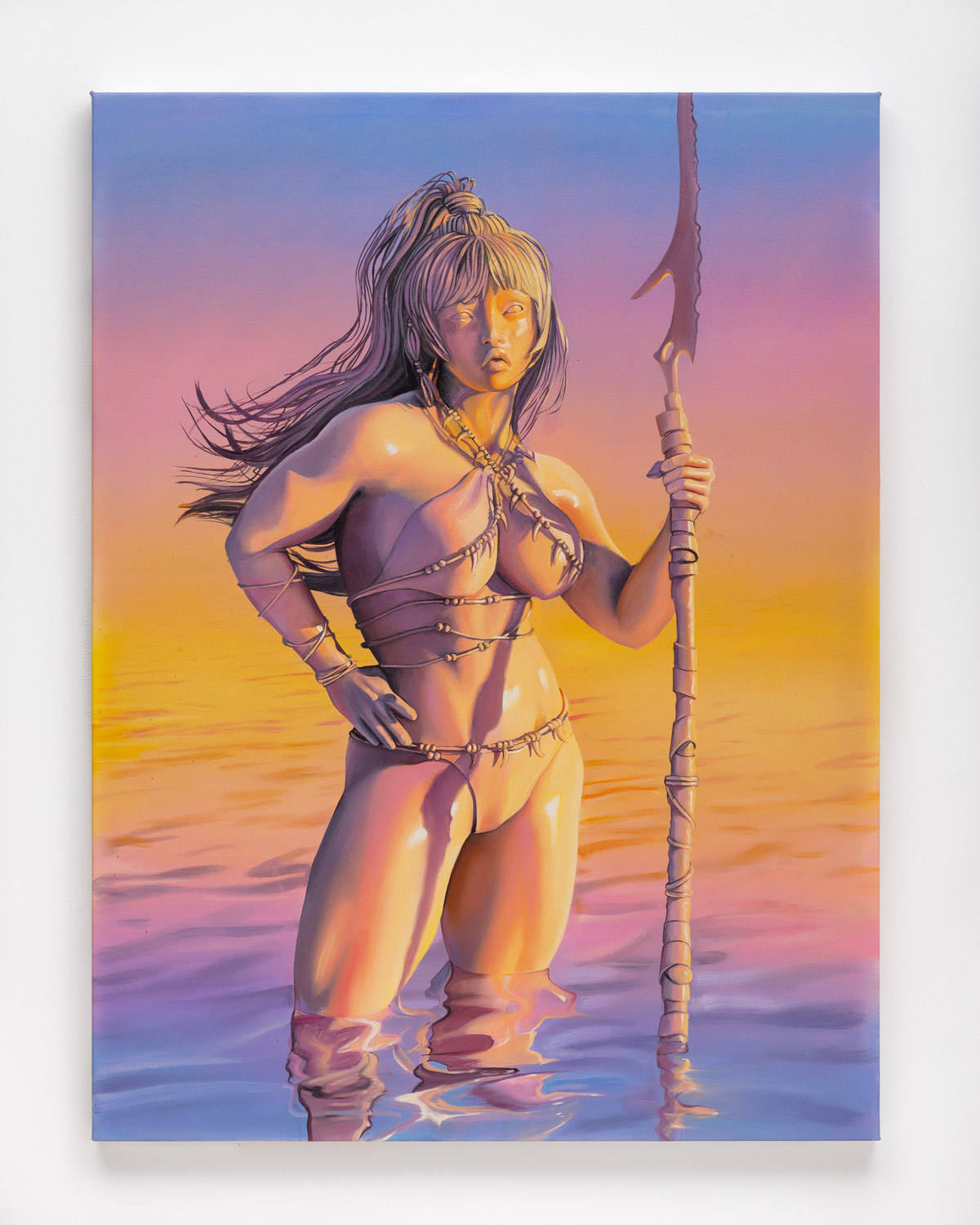

Emma Stern is a New York-based painter and sculptor commonly known for depictions of busty bitches with big blades and lady pirates in miniskirts. The female figures in Emma’s work take on the proportions of anime women – it’s hard not to think of the sweet but wacky Asian girls on IG with hard nose contour and possibly painted freckles, cross eyed posing with furry cat ears and a finger in their mouths. Her paintings have the same untamed yet purposely playful submissive seductive energy. Women with skinny arms, tiny waists and well-rounded boobs and butts, sometimes deliberately flirting with the beholder as they look over their shoulder and throw us a kiss, either spazzing or chilling out in their hot girl universe where no man is to be found. Emma calls them her muses. She sculpts her pink-lilac tinted world and the ladies who inhabit it using 3D software, later translating it into oil paintings, still echoing the digital traces of their precursors – high sheen, with clear sources of light. Here, she’s interviewed by Swedish sculptor Klara Zetterholm.

Klara Zetterholm: Tell me about the process of making your paintings.

Emma Stern: I refer to the work I’m making right now as a “universe creation” project – I’ve always had an interest in such concepts. When I was a little kid, I had an aquarium with a bunch of little fish in it, and I really enjoyed building a little mini-simulation within that. I would tap on the glass to make the fish swim one way and then get them to switch direction. In their little world, I was God.

I don’t want to unpack that psychologically, but I think it always comes back to a near-obsession with world building. I was raised pretty religiously. As a result, I got into creation mythology and was really absorbed by the Book of Genesis, which somehow connects to the work I make today. I don’t only build characters; I build the environments that they populate.

KZ: You mostly paint female creatures and characters, often anthropomorphic or mythological figures like mermaids, elves, centaurs and dragons. Some of these originate from mythologies or fables illustrating a moral lesson. Would you say your world is allegorical or that it consists of some kinds of metaphorical analogies?

ES: I think it can be allegorical or metaphorical but I’m more interested in the mythologies I’m creating myself. I’m more fascinated by fantasy than fable. I definitely paint a lot of elves and mermaids but I do a lot of non-anthropomorphised characters as well. I almost find them more intriguing, because the things that are unusual about them might not be so obvious. In those paintings, it’s more about a subtle uncanniness, since what makes them fantastical or surreal is the colours, the environment or that something is off with the bodily proportions.

KZ: Your paintings depict a place that’s somewhere between fantasy and the prosaic: it’s a mermaid chilling, taking a selfie on her couch, or an elf vacuum cleaning her studio apartment.

ES: Part of fantasy is putting things where they don’t belong. For the exhibition Home Bodies at Carl Kostyál in Stockholm two years ago, I showed some paintings I made in London during the big lockdown over Christmas the previous year. They all wound up being very domestic scenes. It was about all these fantasy creatures doing very mundane housework.

Ursula (Hindsight) 2022, oil on canvas, 72 x 58” Courtesy of the artist and Half Gallery

Tiger Lily (Swamp Thing) 2021, oil on canvas, 48 x 36″ Courtesy of the artist and Half Gallery

KZ: Your French gallery Almine Rech describes your work as “vaguely reminiscent of pop-up ads of the “You Won’t Last 5 Minutes in This Game” variety” which I found very amusing.

ES: I wrote that.

KZ: I love those ads. I still remember the day I realized those games didn’t exist; I was so disappointed. Since you wrote the description, you obviously agree that your work has a clickbaiting quality.

ES: It’s totally clickbait. Clickbait is effective, that’s why it’s called that, and even as a colloquial term, I think it’s really profound. As a concept, I think clickbait is both hilarious and deeply poignant. It represents how the new mind works, the way that our thinking has been utilized and how easily it’s shaped – how very plastic it is. As far as my visual vocabulary goes, I’m definitely borrowing from the clickbait aesthetic.

It’s totally clickbait. Clickbait is effective, that’s why it’s called that

KZ: In another interview you claim DeviantArt to be a source of inspiration.

ES: Really? I think it’s less specific than DeviantArt but that does sound like something I would say! Erotic fan art certainly is an inspiration. It’s not identical but related to the idea of clickbait, where what’s being made is dictated by what’s popular. All fan art forums and message boards for 3D erotica are driven by upvotes, promoting the images that people interact with the most. As an artist or creator, you can kind of game it out, and become your own propaganda machine, if you get smart about it. I love that and I’ve also used some propaganda tools in my art. I love thinking about my art as propaganda. I love cosplaying as my own PR person.

KZ: My favourite genre of DeviantArt or “Rule 34”-esque imagery is the one making inanimate objects sexy, with horny eyes and huge breasts. Like the infamous planesona characters. Or the one with the L’Oréal kids shampoo bottle.

ES: I love those! Have you heard of the movie My Little Toaster about the toaster and all of the household objects coming alive? I don’t think it was supposed to be erotic, it’s a kid’s movie. But I totally had a crush on that toaster.

KZ: You haven’t really dug into this genre yet. Is this something to consider for future projects?

ES: Yes.

KZ: What’s your opinion on the term post-Internet art?

ES: I think all art is post-Internet art now. Otherwise, you’d have to be making art in a vacuum. I’ve been following this conversation for a while, it used to be a lot more interesting. Now the term just applies to everything. What’s Internet culture? How could you possibly relate to something outside or beyond that today? I don’t think you can. I don’t even know if that’s truly a genre of art anymore, I think it’s just a fact, it’s the era we are in.

I love thinking about my art as propaganda. I love cosplaying as my own PR person.

KZ: You work with classic oil painting techniques but you use digital tools to conduct your paintings and you have done some NFTs. Are you into exploring the algorithmic, uncanny vibe of AI?

ES: I’ve spent some time with this medium. I was a beta tester on the first iteration of DALL-E, and I thought it was pretty exciting at first. Then the reality of what it actually means hit me. The implications of AI are pretty terrifying, but it’s not like it’s going to stop, we kind of have to ride this one out. I haven’t really done any substantial writing on the topic yet, but I would like to at some point. You mentioned NFTs and I got on board really early with that whole shitshow as well. I evangelized it. I basically turned my social media into an infomercial for my NFTs which were these dumb little jpegs. Six months down the line I realized that I was really grossed out by it and that I really jumped the gun. Honestly, I regretted how much I spoke about it. I’ve really moved away from that whole economy, because that’s what it is, at least for a foreseeable future. I think we are moving towards a future without objects, without things, so I want to make material work while it’s still viable and relevant.

KZ: What’s your view on topicality in your work? Your aesthetic is closely related to sexual tropes on the Internet, it’s very high rendered but you also reference nostalgic elements in your style of painting and your choice of medium.

ES: The reason I render these images in oil paint on canvas is because it’s important to me that they are seen in the context of art history and the broader tradition of painting, specifically portraiture. I use 3D programmes to design my figures and make my compositions, but I employ Renaissance compositional tools like diagonals, ratios and centre points. There is a bunch of math you can use to make a composition more satisfying. I’ll also adopt some classical gestures – I’ll do a lot like that [makes an elegant hand posture] which is from Botticelli’s Venus, for example. It’s an attempt to tie in art history in my work.

KZ: What kind of relationship do you develop with your virtual muses? Are they part self-portraits?

ES: I always think of them as extended self-portraiture. It’s fun because some of them have become more occurring, there is one that I use more than the rest. It’s probably the one I identify with the most. They all represent facets of me, but they do take on personalities of their own. When I do solo exhibitions, I’ll do like a casting in my head. “Do I have to make new characters? Can I re-use this one? Does this one make sense in the story that I’m trying to tell?”

For a show, I’ll spend four or five months working with the characters and I feel like I really get to know them. As I am painting them, I’m writing stories about them. This is the fiction fantasy part of it all coming up again, right?

KZ: You seem to have a completely relaxed approach to using your own body performatively as part of the spectrum of your work.

ES: Yeah, it’s funny, I feel like I use social media as a long duration performance piece in some ways, but I am definitely doing a character. My virtual self is a proxy for the actual — It’s based on reality but it’s heavily curated.

KZ: I’m a very shy person, do you have any advice for me if I would try to achieve your level of comfort in developing my Internet persona?

ES: It’s funny you ask this, because I feel quite shy too! My therapist has hypothesized that I’ve actually built this online persona as a way to overcome my stage fright. My visual self is my avatar.

KZ: I read your piece about the male gaze in l’Officiel and I just have one question. In the text you claim that enjoyment by definition must be authentic and not ironic. I feel like I enjoy things ironically all the time?

ES: Really? Maybe the context is ironic, but your enjoyment is genuine? If you’re truly enjoying something it must be authentic on some level, even if your description of your enjoyment is ironic. I think about this all the time. For example, the other day I was talking with someone about how I love going to the Olive Garden in Times Square, and you know, I joke and the implication is “because it’s ironic, haha,” but I actually really like it there. It reminds me of growing up middle class in New Jersey, of going there with my high school boyfriend after smoking weed for the first time. And it’s consistent! The menu never changes, there’s never any surprises and frankly I need that kind of stability in my life sometimes. So, when I talk about Olive Garden, sure, I do it with a wink, but beneath that, there is authenticity, a deep love for the brand.

KZ: I would say it’s enjoying something ironically, because you’re still aware of the notion of irony.

ES: Irony and the way that I define it is the absence of authenticity, or the deliberate erasure. If you’re laughing and smiling and having a good time, if you’re enjoying yourself, how do you do that inauthentically?

KZ: Don’t you think one can be in two headspaces at once and really enjoy something because it is so bad?

ES: At a certain point it’s just a semantic argument, but I don’t know. I love stupid and ugly stuff, but it can’t be entirely stupid or ugly. Some part of it must be sincerely enjoyable, unless I just have horrible taste. Which maybe I do, but whatever.

| Interview | Klara Zetterholm |

| Photography | Jeremy Liebman |

| Styling | Mi Märak |

| Photography, of artworks | Daniel Terna |