Metropol’s Ivory Pijin reviews the internet cinema cycle that took place on January 24th during this year’s London Short Film Festival

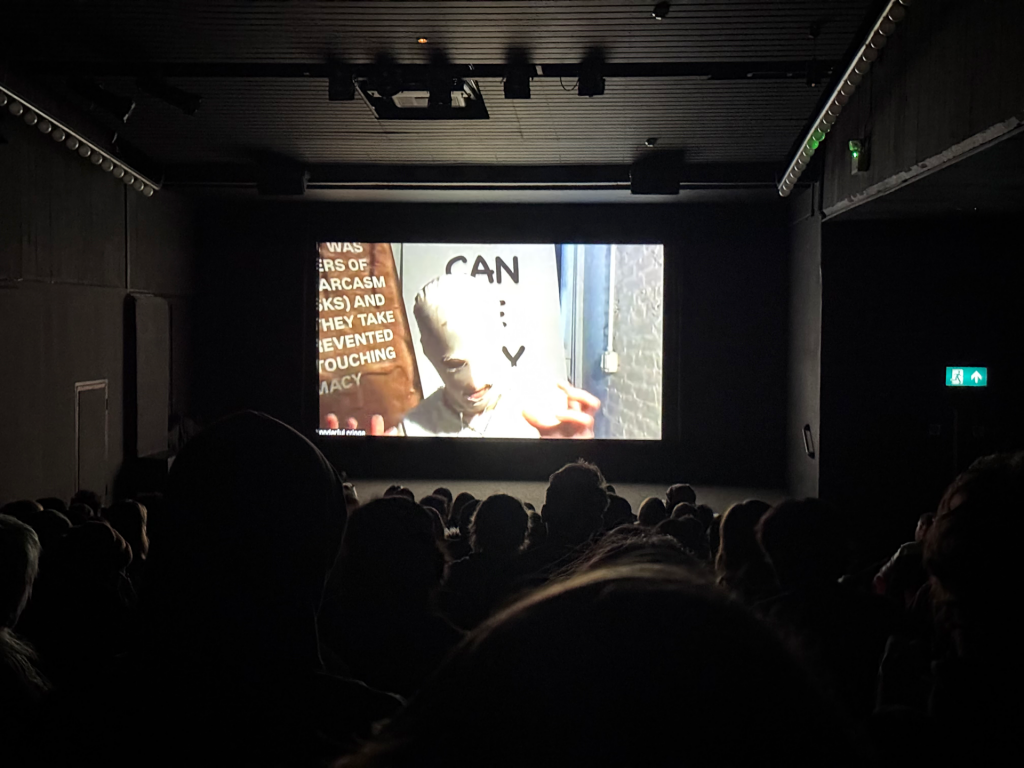

“All good,” I say to the front desk as I’m escorted into the screening. It’s a cold, wet night in London, and I’m at the ICA for the CoreCore programme at the London Short Film Festival. Going in, I feel a tinge of cold sweats, though I’m relieved to have made it in time. I sit at the back of the theatre amongst a group who, with bated breath, are also excited for what might be one of the most unique screenings I’ve encountered in this city.

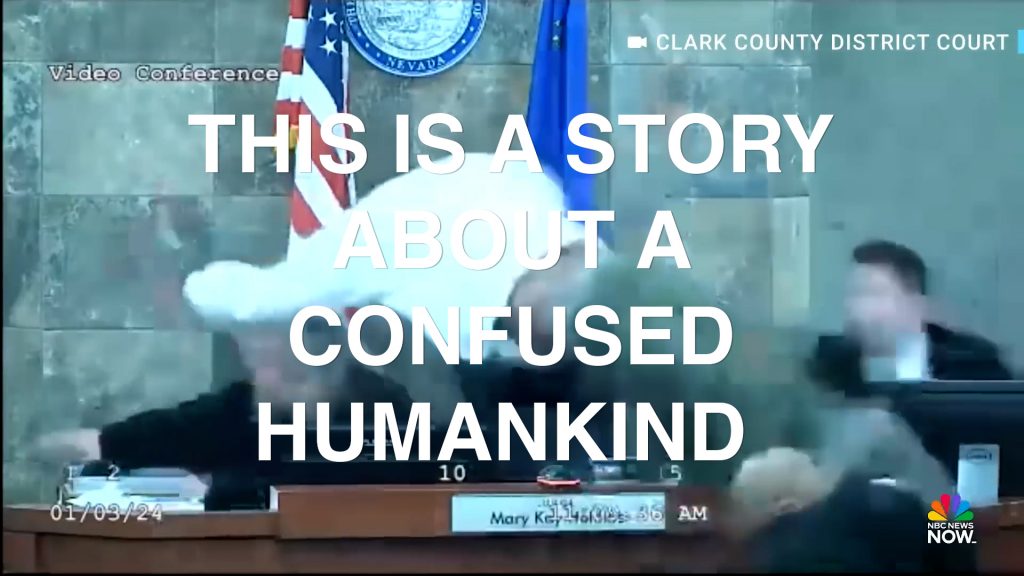

Kieran Press-Reynolds defines CoreCore as a “post-content” or “post-irony” collage movement, but I think it’s something looser than that. For Metropol, the London cultural discovery project I’ve co-created, I spoke to Kieran and various artists and contributors to the genre, and what emerged wasn’t resistance to definition but a new grammar entirely – one native to infinite scroll and algorithmic feed. CoreCore operates through rapid-fire juxtaposition: a politician’s speech cut against someone microwaving ramen, glacial calving footage bleeding into a toddler’s birthday party, all held together by ambient drones or distorted audio fragments. It’s collage at scroll speed, meaning constructed through adjacency rather than narrative. The form mirrors how we actually experience digital life now – not as discrete pieces of content but as an affective blur where a climate disaster headline sits two swipes away from a makeup tutorial. What I can say definitively is that CoreCore is not only a filmic language, but a very specific feeling. And it’s a feeling birthed by overwhelm.

My first encounter with it came during the pandemic, a pivotal moment, also, for numerous artists in the space, as it seemed to mark when the general population had to make an active investment in being online. The first video I saw was a compilation of podcasters like Theo Von and Joe Rogan lamenting the loneliness plaguing society. Was I lonely? Yes. Was I overwhelmed? Yes. Did it speak to me? Also yes. I followed the #corecore hashtag for years, finding it strangely self-soothing, a normalising reminder that modern life is tough and brutal, and that many young people were experiencing this same emotion of doomsday amid an ever-present barrage of content disguising underlying problems of isolation, fear, and feeling cast aside by the system.

The first film takes a journey through the modern internet, from Vines and memes and funny nostalgic content to a much closer, and therefore more disturbing, view of the present: violent scenes, the wreckage left by early optimism. Gameplay clips run alongside someone’s confessional TikTok about their failing relationship. Meme sounds trigger a Pavlovian giggle from the audience, then immediately cut to shaky phone footage of a street confrontation.

The films continue and I’m awestruck, not just by the work itself but by the fact that this notable showing of the genre is happening here in London, the third most surveilled city on the planet. There’s a curiously deep London tone running through each film. People laugh at the jokes – a perfectly timed reaction image– and moment after moment of giggles gives way to the empty void of realisation, the cold hard truth that this is not just a joke or an archive but our current reality. We’re laughing at the editing, at the audacity of the juxtaposition, at our own recognition of these fragments from our feeds.

Artist Zarina Nares comments it’s the most laughs she’s got in a screening and that humour is a good tool for processing the world when it’s dark. It’s an art that Londoners have perfected, and the films seem to know this, leaning into the comedy before pulling the rug. The internet is very American, and the films are rooted in Americanisms we recognise: the binary, flashy images, everything huge and disproportionate to what “reality” offers most of us. Yet here we are, watching them in a basement off The Mall, laughing nervously in the rain-soaked capital of ironic detachment.

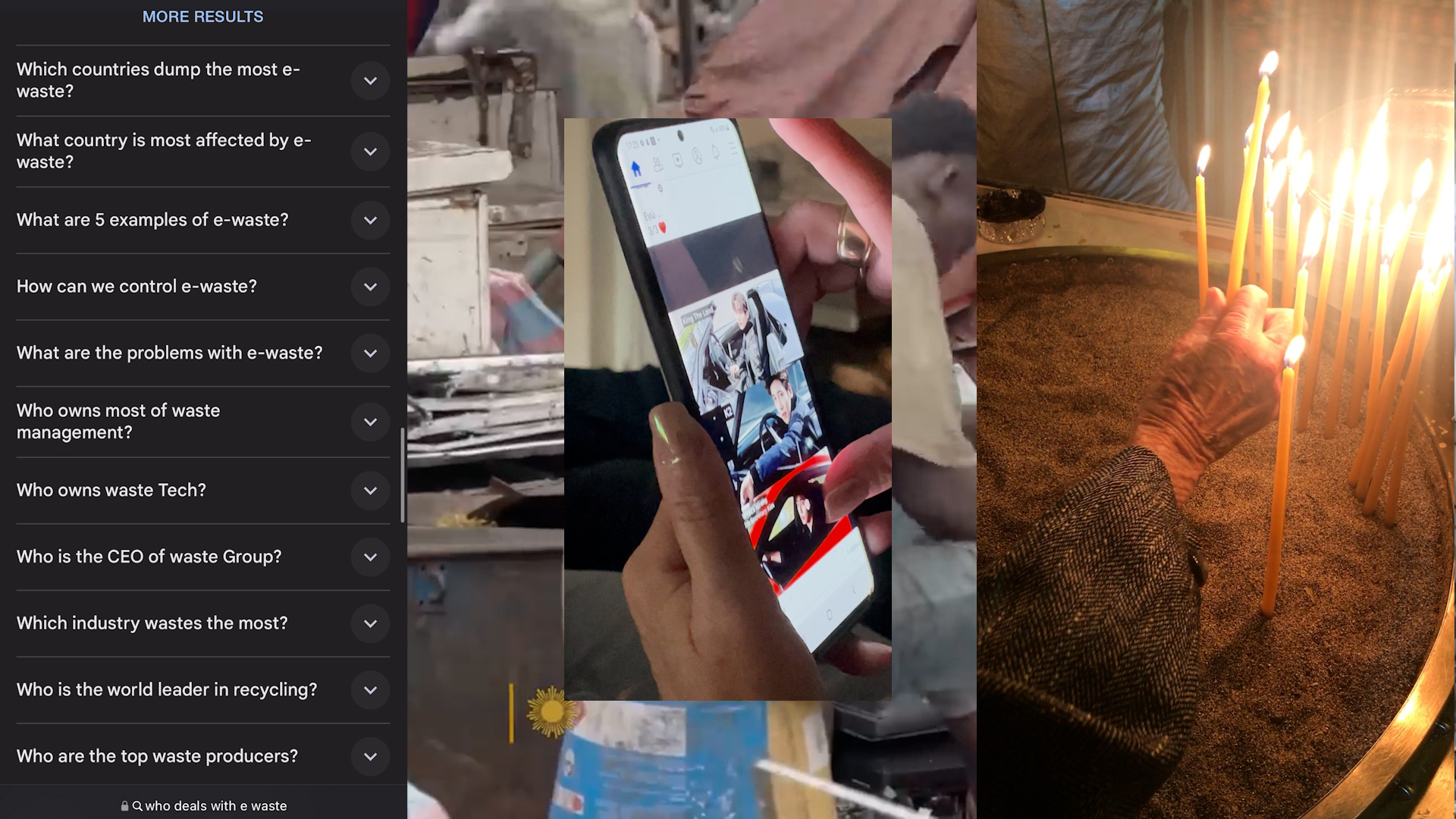

This is another reason the films strike me as so interesting. The doomsday narratives we use to justify our consumption loom like deep dark shadows across the programme, according to filmmaker Nicholas Sanchez. Being terminally online means things have to be catastrophised to gain importance. Many of the films are menacing – not through traditional horror but through sustained disorientation. Audio layers pile up until you can’t distinguish between a news report, someone’s panic attack, and a bass-boosted meme sound. Images strobe faster than you can process: surveillance camera angles, ring doorbell footage of nothing happening, phone screens recording other phone screens in infinite regress. One film lingers on a static shot of an empty video call while distorted voices overlap in the background. Another loops the same 3-second clip of someone scrolling their feed for what feels like minutes, the repetition becoming physically oppressive. The menace comes from recognition: this is what our attention actually feels like now, fractured and trapped and unable to look away. People leave midway through, unable to continue. I notice others check their phones, ironically, to comfort themselves.

Most of all, what one recognises is the quiet desperation that comes from being online. The half-truth, half-irony that never seems to play out fondly.

Motifs and clips run through various films, such as RNG by Redacted Cut and Dana Dawud’s Palcorecore. These are moments that break the illusion of the scroll and show us how networked life seems inorganic yet appeals to utopian motives, from watching a genocide to building awareness to creating resistance. It’s this randomness, as Charlie Bird mentions, that’s truly disturbing. One can’t fully focus on a resolution.

It’s the nature of being available, to want others, to long for things, for connection through networks upheld by underwater cables. A growing anxiety, too, if you’re aware they could be turned off in the event of a global emergency, as explored in Nick Vyssotsky’s Cobwebs Spun Back & Forth In The Sky or in Ruba Al-Saweel’s Plastic Pilgrims (not screened at the event, but seen at Screening Room’s showing the previous week). We trace the literal infrastructure of the internet – those undersea fiber optic cables that carry our data – through fragmented footage, and the eerie vulnerability of networks we pretend are permanent. In the Q&A, a strange precedent is set: it’s pre-recorded, but all participants pretend it was filmed after the screening, creating its own meta-analysis of the form.

Afterwards, I step out onto the wet pavement and instinctively reach for my phone. I catch myself, then do it anyway. The irony isn’t lost on me, but that’s the thing about irony now: noticing it doesn’t free you from it. I walk towards the Tube, scrolling through nothing in particular, the films still flickering somewhere behind my eyes. The city moves around me.

| Writer | Ivory Pijin |