Enlightenment Environmentalist, The Case for Ecomodernism

Is progress sustainable?

A common response to good news about global health, wealth, and sustenance is that it cannot continue. As we infest the world with our teeming numbers, guzzle the earth’s bounty heedless of its finitude, and foul our nests with pollution and waste, we are hastening an environmental day of reckoning. If overpopulation, resource depletion, and pollution don’t finish us off, then climate change will.

To be sure, the very idea that there are environmental problems cannot be taken for granted. Beginning in the 1960s, the environmental movement grew out of scientific knowledge (from ecology, public health, and earth and atmospheric sciences) and a Romantic reverence for nature. The movement made the health of the planet a permanent priority on humanity’s agenda, and it deserves credit for substantial achievements — another form of human progress.

Yet today, many voices in the traditional environmental movement refuse to acknowledge that progress, or even that human progress is a worthy aspiration. While it is true that not all the trends are positive, nor that the problems facing us are minor, it is crucial to understand that environmental problems, like other problems, are solvable, given the right knowledge.

In contrast to the lugubrious conventional wisdom offered by the mainstream environmental movement, and the radicalism and fatalism it encourages, there is a newer conception of environmentalism which shares the goal of protecting the air and water, species, and ecosystems but is grounded in Enlightenment optimism rather than Romantic declinism. That approach is called ecomodernism.

Ecomodernism begins with the realization that some degree of pollution is an inescapable consequence of the second law of thermodynamics. When people use energy, they must increase entropy elsewhere in the environment in the form of waste, pollution, and other forms of disorder. The human species has always been ingenious at doing this — that’s what differentiates us from other mammals — and it has never lived in harmony with the environment. When native peoples first set foot in an ecosystem, they typically hunted large animals to extinction, and often burned and cleared vast swaths of forest.

A second realization of the ecomodernist movement is that industrialization has been good for humanity. It has fed billions, doubled lifespans, slashed extreme poverty, and, by replacing muscle with machinery, made it easier to end slavery, emancipate women, and educate children. It has allowed people to read at night, live where they want, stay warm in winter, see the world, and multiply human contact. Any costs in pollution and habitat loss have to be weighed against these gifts. As the economist Robert Frank has put it, there is an optimal amount of pollution in the environment, just as there is an optimal amount of dirt in your house. Cleaner is better, but not at the expense of everything else in life.

The third premise is that the trade-off that pits human well-being against environmental damage can be renegotiated by technology. How to enjoy more calories, lumens, BTUs, bits, and miles with less pollution and land is itself a technological problem, and one that the world is increasingly solving. If people can afford electricity only at the cost of some smog, they’ll live with the smog, but when they can afford both electricity and clean air, they’ll spring for the clean air. This can happen all the faster as technology makes cars and factories and power plants cleaner and thus makes clean air more affordable.

1.

This idea, that environmental protection is a problem to be solved, is commonly dismissed as the “faith that technology will save us.” In fact, it is a skepticism that the status quo will doom us — that knowledge and behavior will remain frozen in their current state for perpetuity. Indeed, a naive faith in stasis has repeatedly led to prophecies of environmental doomsdays that never happened.

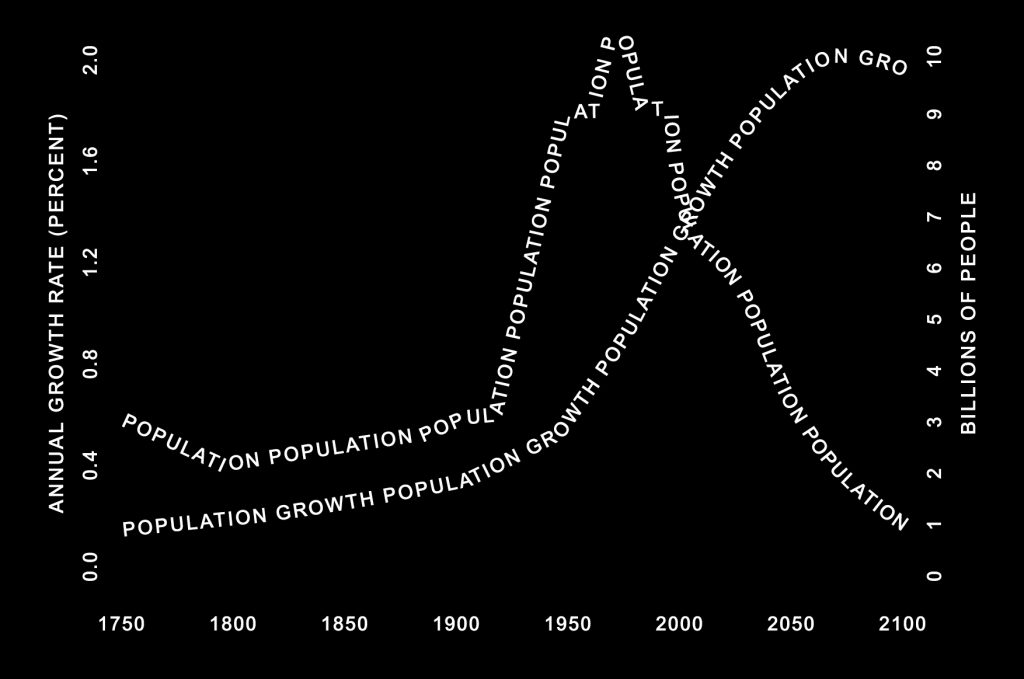

The first is the “population bomb,” which defused itself. When countries get richer and better educated, they pass through what demographers call the demographic transition. Birth rates peak and then decline, for at least two reasons. Parents no longer breed large broods as insurance against some of their children dying, and women, when they become better educated, marry later and delay having children. Fertility rates have fallen most noticeably in developed regions like Europe and Japan, but they can suddenly collapse, often to demographers’ surprise, in other parts of the world. Despite the widespread belief that Muslim societies are resistant to the social changes that have transformed the West, Muslim countries have seen a 40 percent decline in fertility over the past three decades, including a 70 percent drop in Iran and 60 percent drops in Bangladesh and in seven Arab countries.

Figure 1: Population and population growth, 1750–2015 and projected to 2100

The other environmental scare from the 1960s was that the world would run out of resources. But resources just refuse to run out. The 1980s came and went without the famines that were supposed to starve tens of millions of Americans and billions of people worldwide. Then the year 1992 passed and, contrary to projections from the 1972 bestseller The Limits to Growth, the world did not exhaust its aliminium, copper, chromium, gold, nickel, tin, tungsten, or zinc. In 2013 the Atlantic ran a cover story about the fracking revolution entitled “We Will Never Run Out of Oil.” Humanity does not suck resources from the earth like a straw in a milkshake until a gurgle tells it that the container is empty. Instead, as the most easily extracted supply of a resource becomes scarcer, its price rises, encouraging people to conserve it, get at the less accessible deposits, or find cheaper and more plentiful substitutes.

Indeed, it’s a fallacy to think that people “need resources” in the first place. They need ways of growing food, moving around, lighting their homes, and displaying information. They satisfy these needs with ideas: with recipes, formulas, techniques, blueprints, and algorithms for manipulating the physical world to give them what they want. The human mind, with its recursive combinatorial power, can explore an infinite space of ideas, and is not limited by the quantity of any particular kind of stuff in the ground. When one idea no longer works, another can take its place.

Take the supply of food, which has grown exponentially even though no single method of growing it has ever been sustainable. In The Big Ratchet: How Humanity Thrives in the Face of Natural Crisis, the geographer Ruth DeFries describes the sequence as “ratchet-hatchet-pivot.” People discover a way of growing more food, and the population ratchets upward. The method fails to keep up with demand or develops unpleasant side effects, and the hatchet falls. People then pivot to a new method. At various times, farmers have pivoted to slash-and-burn horticulture, night soil (a euphemism for human feces), crop rotation, guano, saltpeter, ground-up bison bones, chemical fertilizer, hybrid crops, pesticides, and the Green Revolution. Future pivots may include genetically modified organisms, hydroponics, aeroponics, urban vertical farms, robotic harvesting, meat cultured in vitro, artificial-intelligence algorithms fed by GPS and biosensors, the recovery of energy and fertilizer from sewage, aquaculture with fish that eat tofu, and who knows what else — as long as people are allowed to indulge their ingenuity.

2.

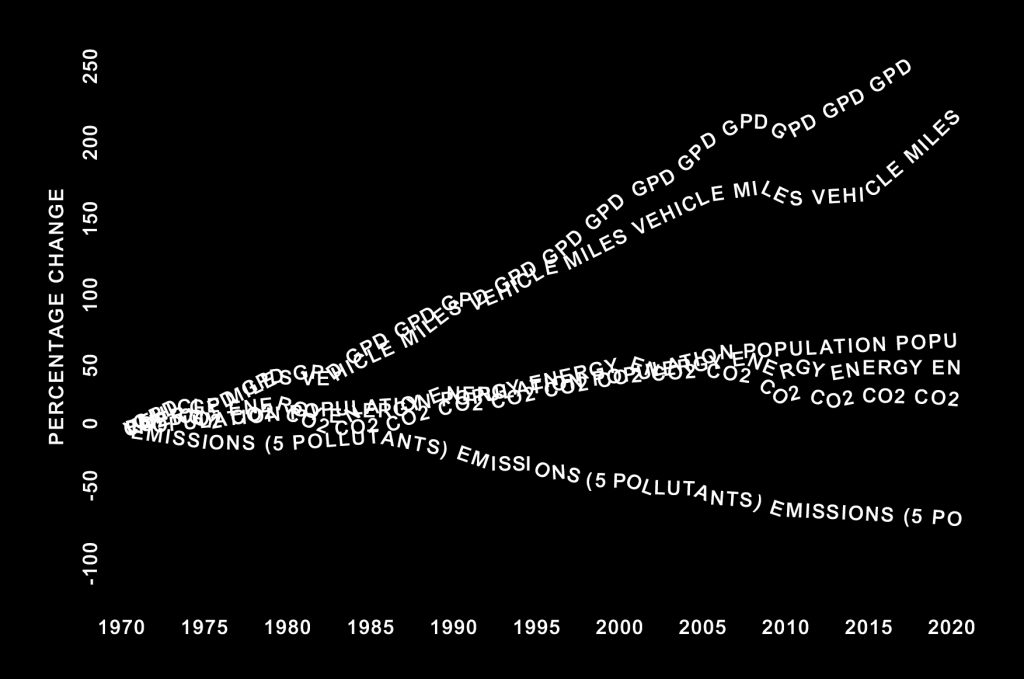

Again and again, environmental improvements once deemed impossible have taken place. Since 1970, when the Environmental Protection Agency was established, the United States has slashed its emissions of five air pollutants by almost two-thirds. Over the same period, the population grew by more than 40 percent, and those people drove twice as many miles and became two and a half times richer. Energy use has leveled off, and even carbon dioxide emissions have turned a corner. These diverging curves refute both the left-wing claim that only degrowth can curb pollution and the right-wing claim that environmental protection must sabotage economic growth and standard of living.

Figure 2: Pollution, energy, and growth, United States, 1970–2015

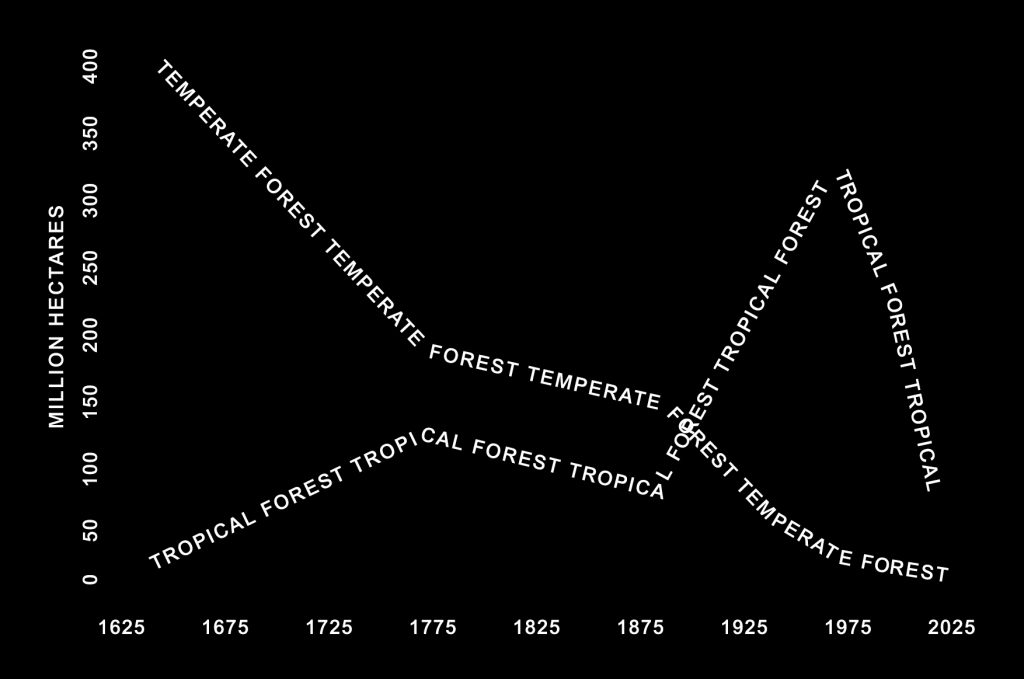

Many of the improvements can be seen with the naked eye. Cities are less often shrouded in purple-brown haze, and London no longer has the fog — actually coal smoke — that was immortalized in Impressionist paintings, gothic novels, the Gershwin song, and the brand of raincoats. Urban waterways that had been left for dead — including Puget Sound, Chesapeake Bay, Boston Harbor, Lake Erie, and the Hudson, Potomac, Chicago, Charles, Seine, Rhine, and Thames rivers (the last described by Benjamin Disraeli as “a Stygian pool reeking with ineffable and intolerable horrors”) — have been recolonized by fish, birds, marine mammals, and sometimes swimmers. Suburbanites are seeing wolves, foxes, bears, bobcats, badgers, deer, ospreys, wild turkeys, and bald eagles. As agriculture becomes more efficient, farmland returns to temperate forest. Though tropical forests are still, alarmingly, being cut down, between the middle of the 20th century and the turn of the 21st the rate fell by two-thirds. Deforestation of the world’s largest tropical forest, the Amazon, peaked in 1995, and from 2004 to 2013 the rate fell by four-fifths.

Figure 3: Deforestation, 1700–2010

The world’s progress on environmental protection can be tracked in a report card called the Environmental Performance Index, a composite of indicators of the quality of air, water, forests, fisheries, farms, and natural habitats. Out of 180 countries that have been tracked for a decade or more, all but two show an improvement. The wealthier the country, on average, the cleaner its environment: the Nordic countries were cleanest; Afghanistan, Bangladesh, and several sub-Saharan African countries, the most compromised. Two of the deadliest forms of pollution — contaminated drinking water and indoor cooking smoke — are afflictions of poor countries. But as poor countries have gotten richer in recent decades, they are escaping these blights: the proportion of the world’s population that drinks tainted water has fallen by five-eighths, the proportion breathing cooking smoke by a third. As Indira Gandhi said, “Poverty is the greatest polluter.”

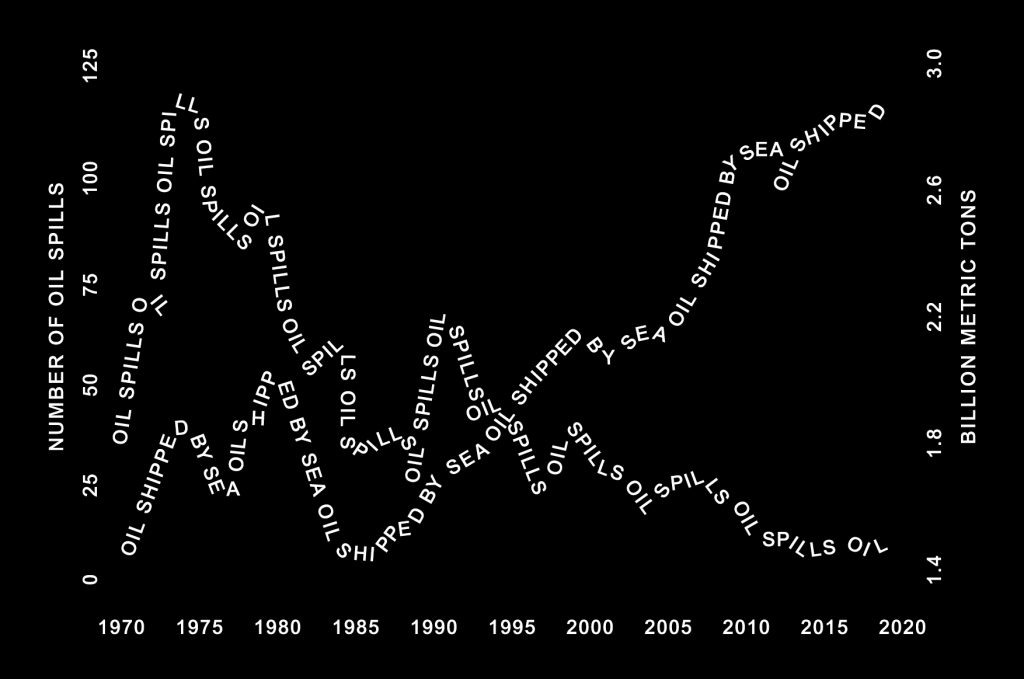

The epitome of environmental insults is the oil spill from tanker ships, which coats pristine beaches with toxic black sludge and fouls the plumage of seabirds and the fur of otters and seals. The most notorious accidents, such as the breakup of the Torrey Canyon in 1967 and the Exxon Valdez in 1989, linger in our collective memory, and few are aware that seaborne oil transport has become vastly safer: the annual number of oil spills has fallen from more than a hundred in 1973 to just five in 2016 (and the number of major spills fell from 32 in 1978 to one in 2016). Even as less oil was spilled, more oil was shipped; the crossing curves in the figure below provide additional evidence that environmental protection is compatible with economic growth. It’s no mystery that oil companies should want to reduce tanker accidents, because their interests and those of the environment coincide: oil spills are a public-relations disaster, bring on huge fines, and waste valuable oil. More interesting is the fact that the companies have largely succeeded. Technologies follow a learning curve and become less hazardous over time as the boffins design out the most dangerous vulnerabilities.

Figure 4: Oil spills, 1970–2016

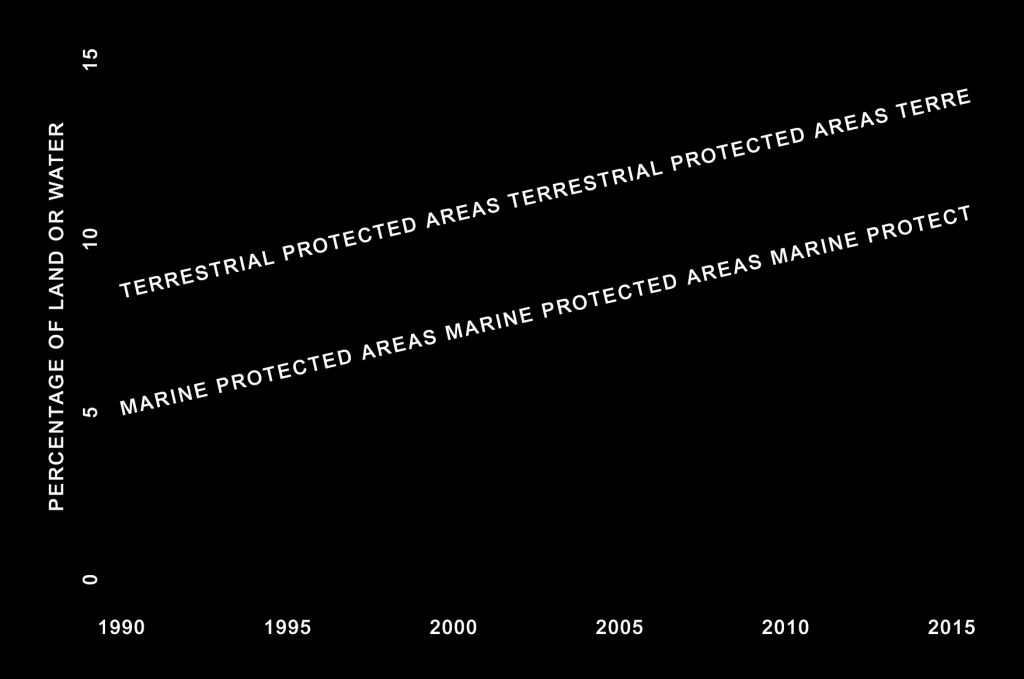

In another advance, entire swaths of land and ocean have been protected from human use altogether. Conservation experts are unanimous in their assessment that protected areas remain inadequate, but the momentum is impressive. The proportion of the earth’s land set aside as national parks, wildlife reserves, and other protected areas has grown from 8.2 percent in 1990 to 14.8 percent in 2014 — an area double the size of the United States. Marine conservation areas have grown as well, more than doubling during this period and now protecting more than 12 percent of the world’s oceans.

Figure 5: Protected areas, 1990–2014

Thanks to habitat protection and targeted conservation efforts, many beloved species have been pulled from the brink of extinction, including albatrosses, condors, manatees, oryxes, pandas, rhinoceroses, Tasmanian devils, and tigers; according to the ecologist Stuart Pimm, the overall rate of extinctions has been reduced by 75 percent. Though many species remain in precarious straits, a number of ecologists and paleontologists believe that the claim that humans are causing a mass extinction is hyperbolic. As Stewart Brand notes, “No end of specific wildlife problems remain to be solved, but describing them too often as extinction crises has led to a general panic that nature is extremely fragile or already hopelessly broken. That is not remotely the case. Nature as a whole is exactly as robust as it ever was — maybe more so. . . . Working with that robustness is how conservation’s goals get reached.”

One key to accelerating conservation is to decouple productivity from resources: to get more human benefit from less matter and energy. This puts a premium on density. As crops are bred or engineered to produce more protein, calories, and fiber with less land, water, and fertilizer, farmland is spared, and it can morph back to natural habitats. As people move to cities, they not only free up land in the countryside but need fewer resources for commuting, building, and heating. As trees are harvested from dense plantations, which have five to ten times the yield of natural forests, forestland is spared, together with its feathered, furry, and scaly inhabitants.

All these processes are helped along by another friend of the earth: dematerialization. Progress in technology allows us to do more with less. Indeed, we may be reaching “Peak Stuff”: of a hundred commodities the environmental scientist Jesse Ausubel has plotted, 36 have peaked in absolute use in the United States, and another 53 may be poised to drop, including water, nitrogen, and electricity.

What these remarkable trends don’t show is that environmental legislation is dispensable — by all accounts, environmental protection agencies, mandated energy standards, endangered species protection, and national and international clean air and water acts have had enormously beneficial effects.[18] Many such gains have been global in scope: The 1963 treaty banning atmospheric nuclear testing eliminated the most terrifying form of pollution, radioactive fallout, and proved that the world’s nations could agree on measures to protect the planet even in the absence of a world government. International treaties on the reduction of sulfur emissions and other forms of “long-range transboundary air pollution” signed in the 1980s and 1990s helped to eliminate the scare of acid rain. Thanks to the 1987 ban on chlorofluorocarbons ratified by 197 countries, the ozone layer is expected to heal by the middle of the 21st century. These successes set the stage for the historic Paris Agreement on climate change in 2015.

3.

Like all demonstrations of progress, reports on the improving state of the environment are often met with a combination of anger and illogic. The fact that many measures of environmental quality are improving does not mean that everything is OK, that the environment got better by itself, or that we can just sit back and relax. For the cleaner environment we enjoy today we must thank the arguments, activism, legislation, regulations, treaties, and technological ingenuity of the people who sought to improve it in the past. We’ll need more of each to sustain the progress we’ve made, prevent reversals (particularly under the Trump presidency), and extend it to the wicked problems that still face us, including the one that is unquestionably alarming: the effect of greenhouse gases on the earth’s climate.

Whenever we burn wood, coal, oil, or gas, the carbon in the fuel is oxidized to form carbon dioxide, which wafts into the atmosphere. Though some of the CO2 dissolves in the ocean, chemically combines with rocks, or is taken up by photosynthesizing plants, these natural sinks cannot keep up with the 38 billion tons we dump into the atmosphere each year. As gigatons of carbon laid down during the Carboniferous Period have gone up in smoke, the concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere has risen from about 270 parts per million before the Industrial Revolution to more than 400 parts today. Since CO2, like the glass in a greenhouse, traps heat radiating from the earth’s surface, the global average temperature has risen as well, by about .8° Celsius. The atmosphere has also been warmed by the clearing of carbon-eating forests and by the release of methane from leaky gas wells, melting permafrost, and the orifices at both ends of cattle. It could become warmer still in a runaway feedback loop if white, heat-reflecting snow and ice are replaced by dark, heat-absorbing land and water, if the melting of permafrost accelerates, and if more water vapor (yet another greenhouse gas) is sent into the air.

If the emission of greenhouse gases continues, the earth’s average temperature will rise to at least 1.5°C above the preindustrial level by the end of the 21st century, and perhaps to 4°C above that level or more. That will cause more frequent and more severe heat waves, more floods in wet regions, more droughts in dry regions, heavier storms, more severe hurricanes, lower crop yields in warm regions, the extinction of more species, the loss of coral reefs (because the oceans will be both warmer and more acidic), and an average rise in sea level of between 0.7 and 1.2 meters from both the melting of land ice and the expansion of seawater. Low-lying areas would be flooded, island nations would disappear beneath the waves, large stretches of farmland would no longer be arable, and millions of people would be displaced. The effects could get still worse in the 22nd century and beyond, and in theory could trigger upheavals such as a diversion of the Gulf Stream (which would turn Europe into Siberia) or a collapse of Antarctic ice sheets. A rise of 2°C is considered the most that the world could reasonably adapt to, and a rise of 4°C, in the words of a 2012 World Bank report, “simply must not be allowed to occur.”

To keep the rise to 2°C or less, the world would, at a minimum, have to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by half or more by the middle of the 21st century and eliminate them altogether before the turn of the 22nd. The challenge is daunting. Fossil fuels provide 86 percent of the world’s energy, powering almost every car, truck, train, plane, ship, tractor, furnace, and factory on the planet, together with most of its electricity plants. Humanity has never faced a problem like it.

One response to the prospect of climate change is to deny that it is occurring or that human activity is the cause. It’s completely appropriate, of course, to challenge the hypothesis of anthropogenic climate change on scientific grounds, particularly given the extreme measures it calls for if it is true. The great virtue of science is that a true hypothesis will, in the long run, withstand attempts to falsify it. Anthropogenic climate change is the most vigorously challenged scientific hypothesis in history. By now, all the major challenges have been refuted, and even many skeptics have been convinced. A recent survey found that exactly four out of 69,406 authors of peer-reviewed articles in the scientific literature rejected the hypothesis of anthropogenic global warming. Nonetheless, a movement within the American political right, heavily underwritten by fossil fuel interests, has prosecuted a fanatical and mendacious campaign to deny that greenhouse gases are warming the planet.

Another response to climate change, from the far left, seems designed to vindicate the conspiracy theories of the far right. According to the “climate justice” movement popularized by the journalist Naomi Klein in her 2014 bestseller This Changes Everything: Capitalism vs. the Climate, we should not treat the threat of climate change as a challenge to prevent climate change. Rather, we should treat it as an opportunity to abolish free markets, restructure the global economy, and remake our political system. In one of the more surreal episodes in the history of environmental politics, Klein joined the infamous David and Charles Koch, the billionaire oil industrialists, in helping to defeat a 2016 Washington State ballot initiative that would have implemented the country’s first carbon tax. Why? Because the measure did not “make the polluters pay, and put their immoral profits to work repairing the damage they have knowingly created.”

How, then, should we deal with climate change? Deal with it we must. I agree with the climate justice warriors that preventing climate change is a moral issue because it has the potential to harm billions, particularly the world’s poor. But morality is different from moralizing, and is often poorly served by it. It may be satisfying to demonize fossil fuel corporations, but that won’t prevent destructive climate change.

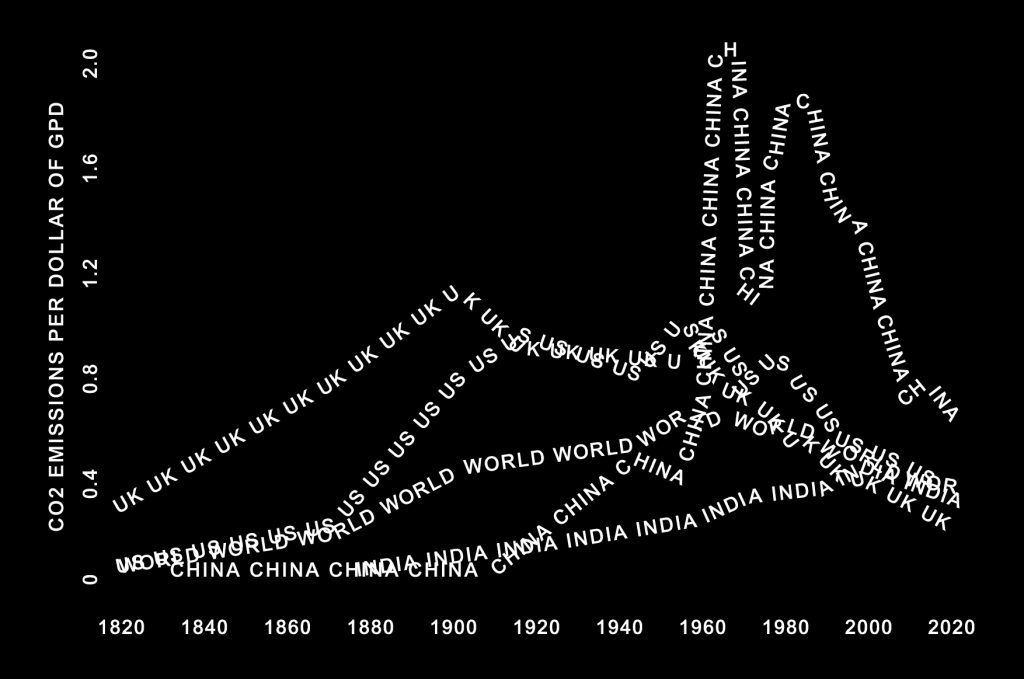

The enlightened response to climate change is to figure out how to get the most energy with the least emission of greenhouse gases. There is, to be sure, a tragic view of modernity in which this is impossible: industrial society, powered by flaming carbon, contains the fuel of its own destruction. But the tragic view is incorrect. The modern world has been progressively decarbonizing. When rich countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom first industrialized, they emitted more and more CO2 to produce a dollar of GDP, but they turned a corner in the 1950s and since then have been emitting less and less. China and India are following suit, cresting in the late 1970s and mid-1990s, respectively. Carbon intensity for the world as a whole has been declining for half a century.

Figure 6: Carbon intensity (CO2 emissions per dollar of GDP), 1820–2014

Some optimists believe that if the trend is allowed to evolve from low-carbon natural gas to zero-carbon nuclear energy, the climate will have a soft landing. But only the sunniest believe this will happen by itself. Annual CO2 emissions may have leveled off for the time being at around 36 billion tons, but that’s still a lot of CO2 added to the atmosphere every year, and there is no sign of the precipitous plunge we would need to stave off harmful outcomes. Instead, decarbonization needs to be helped along with pushes from policy and technology, an idea called deep decarbonization. The success of deep decarbonization will hinge on technological breakthroughs on many frontiers, including advanced nuclear technologies that are cheaper, safer, and more efficient than today’s light-water reactors; batteries to store intermittent energy from renewables; Internet-like smart grids that distribute electricity from scattered sources to scattered users at scattered times; technologies that electrify and decarbonize industrial processes such as the production of cement, fertilizer, and steel; liquid biofuels for heavy trucks and planes that need dense, portable energy; and methods of capturing and storing CO2.

4.

Humanity is not on an irrevocable path to ecological suicide. As the world gets richer and more tech-savvy, it dematerializes, decarbonizes, and densifies, sparing land and species. As people get richer and better educated, they care more about the environment, figure out ways to protect it, and are better able to pay the costs. Many parts of the environment are rebounding, emboldening us to deal with the admittedly severe problems that remain.

First among them is the emission of greenhouse gases and the threat they pose of dangerous climate change. People sometimes ask me whether I think that humanity will rise to the challenge or whether we will sit back and let disaster unfold. For what it’s worth, I think we’ll rise to the challenge, but it’s vital to understand the nature of this optimism. The economist Paul Romer distinguishes between complacent optimism, the feeling of a child waiting for presents on Christmas morning, and conditional optimism, the feeling of a child who wants a treehouse and realizes that if he gets some wood and nails and persuades other kids to help him, he can build one.

We cannot be complacently optimistic about climate change, but we can be conditionally optimistic. We have some practicable ways to prevent the harms and we have the means to learn more. Problems are solvable. That does not mean that they will solve themselves, but it does mean that we can solve them if we sustain the benevolent forces of modernity that have allowed us to solve problems so far, including societal prosperity, wisely regulated markets, international governance, and investments in science and technology. Far from licensing complacency, our progress at solving environmental problems emboldens us to strive for more.

***

| Words | Steven Pinker |