in conversation with Whitney Mallett

Thomas Barger has a smile you could call disarming. When it cracks open his face, his hammerhead-shark eyes flash between embarrassed and entertained. Honest, humble, a little bashful, because he’s all of these things, it was hard to feel offended when he changed our plans. He was supposed to have me over at his Fort Greene apartment to make baked potatoes — something about how stabbing their skins with a fork relates to the process of making his latest sculptures — but then he suggested we meet at a park near his studio instead. A friend had made him second-guess the plan: Really, your home, isn’t that a little intimate for an interview? I thought, duh, that’s the whole point of an interview: a performance of intimacy, a simulation. But I’d just sat down on the bench in the hot sun and felt bad about being late. This didn’t seem the right tone to start out on.

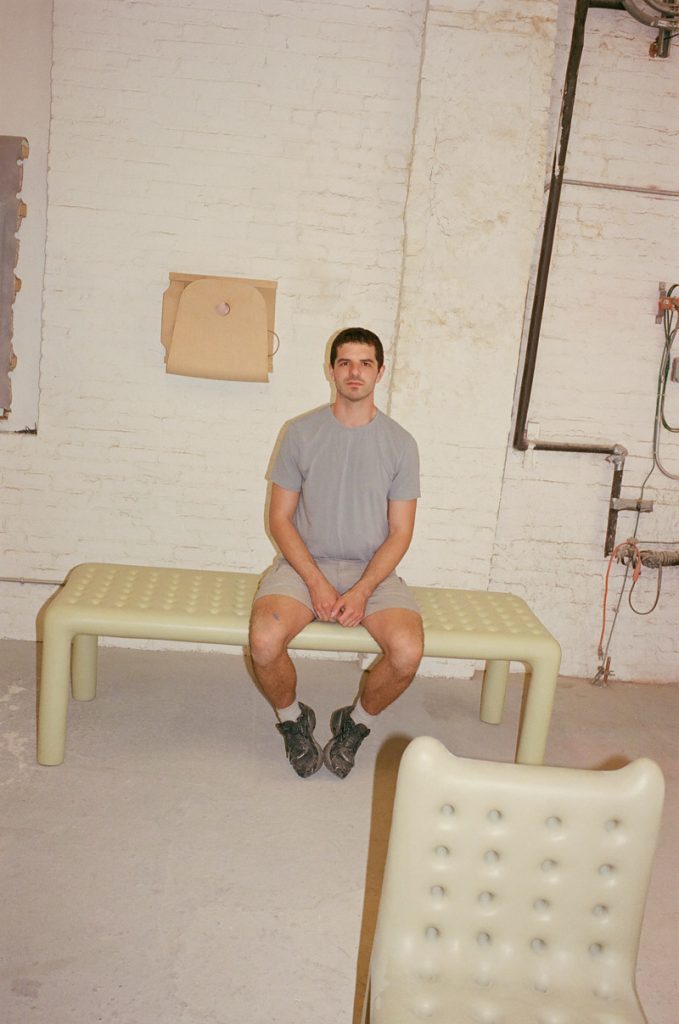

I asked about South Korea instead. Barger, who lives in New York, was just back from a six-week residency at Galerie HeA in Seoul, which culminated in an exhibition of works he’d made during the time, including variations of the hard-puffy chairs for which he’s best known: upright with straight backs, each one’s wooden structure coated with layers of paper pulp and wood glue that dries stiff and inflexible but lends them a thickness resembling something plush or fleshy.

My work isn’t just furniture. It’s also sculpture and mixing the two together. But this was basically a furniture show, chairs and benches, a few wall works and a couple little sculptures. I’d never done a residency like that. I think it was special in the way I had limited time, so I made work quicker, which had its frustrations. You’re used to spending a lot of time making in a way and you have to adapt. You can’t make it the same way you normally do. I started making things quicker and that included making things less smooth. I added a new texture because it helped save time finishing, which was really neat. Over the last few years I have gotten really into the finish of things and almost removing the texture, so bringing back texture was really exciting, even though it’s just on this surface level, that was a big deal for me.

In the recording of our conversation there’s cross audio of a reggaeton track with laser sound effects, coming from a group at the park congregated around a speaker and a couple motorbikes, maybe 20 yards away. Thomas asks:

Is this distracting, the music?

Then he laughs, a melodic he he he like a pony’s gentle bray, and decides, we don’t need to go anywhere quieter.

It’s okay.

Thomas has a kind of calm about him that makes sense when you find out he grew up on a cow farm. Not just cattle, actually, corn and beans too, he tells me. He studied architecture in his home state of Illinois before moving to New York to work at an architecture studio, his sculptural-furniture practice something he started experimenting with on evenings and weekends because he missed the tactile way he’d made work in school.

I started exploring making work, everything really hands on. It was almost a reaction to an architecture studio where everything was kind of being done on the computer. Growing up on a farm, making things with my hands just felt better.

Barger has a very distinct formal vocabulary. His pulp-coated furniture is often described as cartoonish or what you’d expect to see in a Wallace & Gromit animation, and like those big red boots (the annoying ones all over the feeds during fashion week this past February, which memes quickly linked to the Dora the Explorer monkey), his chairs perform well for the algorithm. Their tactility is a reaction to screen-based culture, birthed from their maker wanting to spend less time moving a mouse around to generate renders while their Who Framed Roger Rabbit effect, a collision of cartoon and real worlds, captures the hybrid mode of contemporary living, where the virtual is part of everyday experience. Yet at the same time, Barger’s chairs are nothing like those annoying boots because they don’t feel like a gimmick at all. They keep our attention for more than a viral second because they have other tensions in them, beyond their abstraction of chairness and a post-screen understanding of Platonic form.

My pieces have this curviness and softness that make them approachable, when that softness is masking content that’s more serious. A lot of curvy work or thick work gets displaced as whimsical or jokey. The longer I’m making this work, the more I’m exploring what those serious inspirations are that I’m sometimes masking.

Barger circles around the idea that these inspirations are connected to his background, growing up religious in the rural Midwest, a traditional, conservative environment while being gay. One of his biggest influences is a straight-back pulpit chair.

The first few years of making work I didn’t actually know where the inspiration or content was coming from. And I think it was only after two or three years of making these chairs repetitively over and over that I realized what I was doing. I went home for a wedding and I was like, “oh, wow, these pulpit chairs are so similar, but they’re just scaled in a different way.” The ones I’d been making were much smaller than the pulpit chairs found in a church. After that, I started making these chairs that were much taller, a more imposing scale, like six feet. The ones for the last show I had in New York were really intense. Pointy. Yeah, so I went a little too intense with those, I think, with the form and the colour. They’re so different from the smaller ones I started out making that were super chunky and fun. I’ve explored why I keep returning to this specific form, this specific shape, this rigid back, and I think in the more recent work, where the title is like Greasy Hole Pulpit Chair, it’s a culmination of a sexuality and a religious aspect in one that’s masked over in a design context — which is why it gets confused a lot of the time.

Barger seems to find some freedom in the design context too, the utilitarian nature of his work rescuing it from the confines of too much reductive interpretation.

I really enjoy making functional work and not all of it has that loaded seriousness to it, so it’s like a huge mix.

The longer I’m making this work, the more I’m exploring what those serious inspirations are that I’m sometimes masking

I understand the artist’s reluctance to pin down too definitively the meaning of their work, even though there are many incentives to making one’s self legible. These days perhaps more than ever, the market demands a certain mode of discursive posturing, and as an art-adjacent writer, I’m often in the business of helping craft the textual armaments that can boost an art object’s commercial value, writing profiles, reviews, press releases, and catalog essays. Maybe framing the demand for all this writing exclusively as a function of the market is too cynical. Of course, writing can help a work be understood. But when the modernist mode of interpretation (X + Y = Z) gets too simplified, it feels like commodification. Or worse, bullshit. At any rate, I think the tides have turned against writing about what a work means in too abstract terms. We’re all a little exhausted by the pretensions of art speak. Still we need to tell stories. I mean, I need to, to pay my bills, it’s my trade. But also storytelling is a fundamental part of being human.

What I find most compelling about Barger’s story is the compulsive way he was drawn to make work in a way he didn’t understand himself for a long time. Over and over again he was making these chairs with a religious reference, which choreograph their user’s behavior, demanding a relatively rigid seated posture. Then he was papering over the hard lines of this foundational structure with something softer, giving his chairs brightly colored finishes that added to their playful childlike naiveté, but with all those holes. He didn’t know exactly why this was the work he was drawn to making as a 20-something in a big city where for the first time there was enough breadth to explore his sexuality. It’s beautiful the way we remain mysteries even to ourselves. And I won’t say all work driven by this authentic impulse to unearth and reconcile is good work. But I will say I think the alchemy that happens when these things are manifesting in the work subconsciously is almost always more interesting than when someone sits down and says what form, color, material to use to symbolize something like repression or transformation. I hate art like that. It’s too one-to-one and feels dead on arrival. Barger’s sculptures are not like that. As they trace a kind of eroticism in restriction, there’s also something alive in their fugitive confessions and strategies of refusal.

There’s a shame element in even opening up about it. Making work about it and exploring it, then being able to talk about it is the next step. It’s very vulnerable.

I think with “it” Barger is referring to his sexuality, but I also think “it” could be a number of things, and maybe there’s something generative in leaving open some of that ambiguity.

I’m still exploring my own hang ups with these things, but I find a lot of meat there when I’m in the studio. I think a lot of people can relate to it. It’s not always so specific to a Christian experience or a farming experience. Like of course, the pulpit chair is very specific, but I’ve also made these chair-back wall sculptures over the past few years that I feel have a really traditional experience and then intentionally combined with a sexuality. I’m really excited about these conflicting identities and putting them in a sculpture.

Making work about it and exploring it, then being able to talk about it is the next step. It’s very vulnerable.

You could say Barger has experienced meteoric success. At only 25, he had his first solo exhibition at Salon 94 Design, the leading blue-chip tastemaker of artist-made furniture, and the gallery represents him today. Speaking of stories, they tell a good one on their website of Barger’s beginnings, moving to New York City as a 22-year-old and making money as a dog walker, a chance encounter leading to his DIY paper pulp technique:

While on his dog walking route, Barger noticed massive recycling bags filled with paper documents outside a West Village police station on Charles Street, and began dragging them home and shredding the paper into pulp using a Cuisinart. The pulp was then molded into chairs, dried, sealed with resin, and finally painted.

A couple years ago Barger had a solo show at the Shaker Museum, the exhibition housed in the Meeting House at Hancock Shaker Village in Massachusetts, as part of a series where artists and designers presented their own sculptures in dialogue with Shaker design. Heaven Bound, the title of Barger’s 2021 presentation, included a towering nine-foot-tall Tall Pulpit Chair surrounded by a circle of smaller Shaker chairs all facing inward. Another piece, The Tall Buildings Artistically Reconsidered,consisted of a wicker basket (a repeating rural-domestic reference in Barger’s oeuvre) with a sort of pointy hat seven-feet-tall that echoed the chimney of the Meeting House’s black wood-burning stove it was installed across from.

The show was a really special experience because the Shakers as a group tie together farming, design, and Christianity, and those things are really central to my experience. I tried to tie a lot of those things into single sculptures, which was really challenging. And it was really inspiring because Shaker furniture, the way they make things, they’re all done so beautifully and so nicely, that I got really obsessed with making the surfaces of my works so smooth for them to live in a Shaker space, which is so well-constructed, and then surrounded by all these well-constructed objects. I was working on this show for two years during Covid. It was originally supposed to only be six months but then the date got postponed because of the pandemic, so I kept on exploring these themes in my work and they kept on becoming more complicated and layering over each other. That was a really exciting show for me. The Shakers are definitely inspiring.

At some point while I was talking with Barger in the park, I realised I’d been wearing my sunglasses the whole time. They’re big black visor-like shades that kind of look like the sunglasses blind people wear, which is to say they conceal a lot of my face, and I was sitting there asking someone to reveal so much of themselves to a stranger in eyewear that almost amounted to a disguise. Now after talking for almost an hour, it felt more conspicuous that I’d been wearing these because when I sat down we were in the direct sun, but the light in the sky had changed and was filtering through the canopy of tree branches above us, the shades at present a little much considering this cover. I apologised about it and took them off, but not before I turned off the recording, wondering, if I’d revealed myself earlier, whether it would’ve changed how comfortable Barger would’ve been talking about some of the more vulnerable stuff.

Maybe it was taking off the shades or maybe the gesture of ending the audio surveillance, the interview officially over, that we got a little more intimate then, but because the recording ends before, I’m going to have to paraphrase the rest of the story from memory. I said something about how I’ve been trying to figure out the difference between oversharing and vulnerability, how I used to use the former as a defense mechanism to avoid the latter. And then Barger showed me this meme he likes. It’s a clip of Regina George in Mean Girls having a tantrum breaking stuff in her bedroom with the caption: “Me remembering how I overshared when I could have been mysterious.” I don’t remember if he said so explicitly that this is how he feels after interviews, but I did wonder if this is maybe how he felt after this specific interview. And I also remember thinking I feel like we’re friends now, maybe we will hang out sometime again, I like this guy. I didn’t say it though. My sweater had fallen onto the ground under the bench by our feet. I brushed off the dirt and dead grass that clung to the chunky knit and we walked a few blocks together, talking about our boyfriends and living alone versus living with partners, before we parted ways, Barger heading back to his studio and me in search of an ice coffee.

A few weeks later, I came across a meme that reminded me of Barger, a photo of Y2K-era Hillary Duff captioned: “You can still be mysterious after oversharing because in that moment everyone is thinking, ‘why would she say that.’” I followed him on Instagram to share it.

| Photography | Clément Pascal |

| Interview | Whitney Mallett |