The Junction Maker

Hans Ulrich Obrist is a renowned person in the world of contemporary art, currently holding the position as Artistic Director at the Serpentine Galleries in London. Born 1968 in Zürich, Switzerland, Obrist has established himself as a visionary in the field.

Hans Ulrich Obrist’s first exhibition The Kitchen Show

Location: His student apartment in St. Gallen

Amount of visitors: 29

Lesson learned: “Do it”

Astrin Birnbaum: What is curating to you? In what ways are curating and storytelling connected?

Hans Ulrich Obrist: When I was young, you talked about Austellungsmacher (“exhibition makers”) rather than curators. Harald Szeemann was an “Ausstellungsmacher”, Kasper König was an “Ausstellungs-macher”. When I was in high school in Switzerland, Joseph Beuys gave a lecture in which he talked about the arrival of his new concept of art, his expanded “Kunstbegriff.” Inspired by that idea I thought to myself: If an artist is talking about an expanded version of art, there should be an expanded version of curating. I started to think about ways to go beyond the exhibition. I don’t make exhibitions only of objects – I bring people, non-objects and hyper-objects together. That’s different from traditional curating and from being an Ausstellungsmacher. I once asked J.G. Ballard to help me describe what I do. He said I was a junction maker. As part of making all these junctions, there is of course storytelling. And today some stories are more urgent than ever.

AB: How did you get into curating?

HUO: I was waiting for quite a long time to actually produce something. First, I wanted to learn. I always read about the “Lehr- und Wanderjahre.” I come from a family where there was no possibility to travel much, but I took night trains. As a student, you could have this Interrail ticket that would let you travel all over Europe. I would basically travel for thirty days, to thirty cities, spending nights on the trains. I went to Turin, then to Rome, then to Vienna, then to Berlin; all over Europe, North and South. Those were my Lehr- und Wanderjahre, I would just go and see many, many exhibitions. I was still in university at that time, but I did it during my long breaks. I went to see a hundred artist studios. After all that travelling I felt ready to do something. I was 22 and still enrolled at the University of St. Gallen at that time, when Peter Fischli och David Weiss came and visited me at my student apartment. They suggested we’d turn my kitchen, which at that time was packed with books, into an exhibition. So they installed an altar of food and Christian Boltanski projected a candle where you usually put your rubbish, Hans-Peter Feldmann said he wanted the fridge. Frédéric Bruly Bouabré made life size drawings of roses, coffee, milk and flowers. This was how my first exhibition, The Kitchen Show, came about. It lasted for three months and it had twenty-nine visitors. The Kitchen Show was really a DIY way of getting started. It’s an important lesson: You should not wait until you are given an opportunity, you should create it! It’s the “do it” mentality.

AB: Could you describe your philosophy of curating? How do you craft a narrative through curating?

HUO: The narrative always emerges through conversations with the artist. For me, it’s all about looking and listening to the artist. I’ve always derived an exhibition from multiple conversations, with philosophers, architects, scientists. It’s my job to somehow bring it together, I construct the narrative from these conversations.

AB: Curating is sometimes regarded as a form of artistic practice in itself. How do you navigate between curating as a form of creative expression and curating as a platform to showcase the artworks of others?

HUO: It’s never really been an art form for me. I see myself as an enabler. For me, it’s about listening to artists, to hear about their unrealised projects, utopias and dreams. Then I try to make them happen. Since the 2000s, I’ve worked mostly on solo shows – most of the group shows I’ve curated, I did in the 90s. I feel you can get very, very deep into an artist’s world when you do a solo show. But then of course, every now and then, I want to make something that’s more synthetic. Like the group exhibition Worldbuilding, which is at the Julia Stoschek Foundation in Düsseldorf until December this year, and simultaneously, until December, at the Centre Pompidou-Metz. The show happens at two places at the time. It can even happen in more places, because it’s a show with technology. There is no transport involved. The show looks at video games. I have been really struck by how many artists work with video games nowadays, and also how video games are a possibility for artists to do world building. The show gives some kind of overview of what’s happening in that field.

My shows are about learning and improving, and that’s also why video games are so interesting. They’re very different from Hollywood movies, or any kind of feature films – once those are launched nothing really changes. But with video games, once they’re out on the market, they keep changing and improving. That’s what my exhibitions do. When they go to a city they learn from that city and they hopefully get better. The research continues.

If an artist is talking about an expanded version of art, there should be an expanded version of curating

One of my biggest projects over the last couple of years is my Instagram, which is like a group show. Every day, I ask an artist, architect or designer to contribute with a handwritten sentence. This project tells a lot about my methodology, it’s very open to chance. Initially it was Ryan Trecartin who downloaded the Instagram app on my phone, I didn’t know what to do with it. A bit later I had a conversation about handwriting with Umberto Eco, he was worried that handwriting was disappearing and thought we needed to do something about it. He was the one giving me the task to save handwriting. I kind of forgot about it until I was on holiday with Etel Adnan, Simone Fattal and my partner Koo Jeong A in France. We were hiding from the rain in a cafe for hours. I went on my phone to answer emails, but Etel, who was already in her eighties, did not have a smartphone, so she took out a little notebook and wrote a poem. There it all came together! I meet artists everyday and ask them to write something.

They suggested we’d turn my kitchen, which at that time was packed with books, into an exhibition

AB: Collaboration has been a recurring theme in your work, as you frequently engage with artists, writers, and thinkers from various fields. Could you elaborate on how these collaborations enrich the curatorial process?

HUO: I think we need interdisciplinary in our time. We have a mission to break down the silos of institutions and industries. At Serpentine Galleries we work with our own ecology team as well as artists and scientists in the “Back to Earth” project. I grew up as an only child. I come from a small village in Switzerland, which in itself is a rather lonely experience. There was no big city around where I lived and I didn’t have any friends or siblings. Since then, I’ve always had a great urge to connect and collaborate with other people. I think my urge to work with people comes as a reaction to my lonely childhood. I love the idea of having an exchange, to have a sparring partner.

For Il Tempo del Postino, with Philippe Parreno, we basically invited artists to collaborate on an opera. We wanted to know what would happen if artists were given time on a stage rather than space in a museum. Part of my agenda is that we have to break down the silos of society. We can only solve the big issues of the twenty-first century if we work together – art, science and technology all have a role.

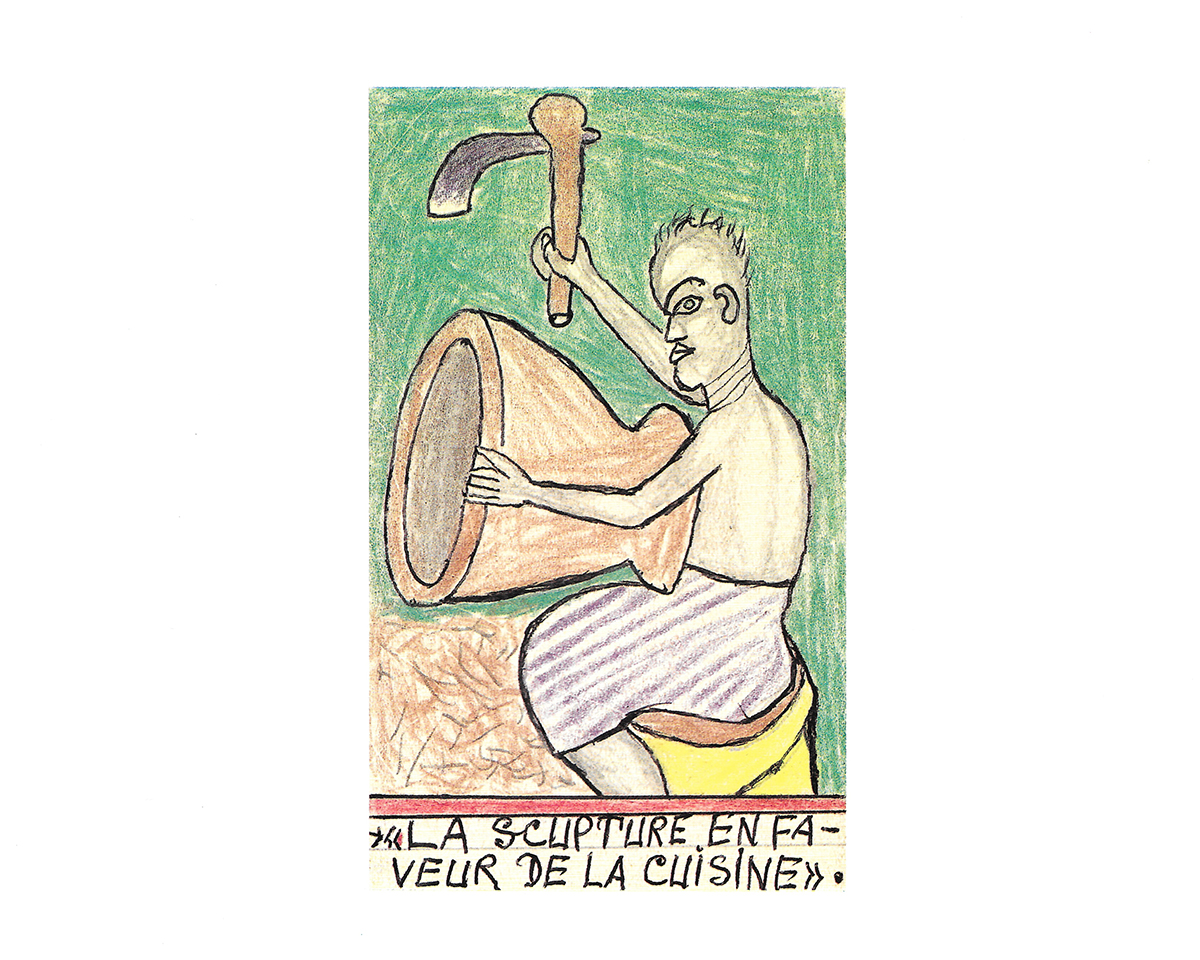

Peter Fischli and David Weiss, contribute to The Kitchen Show

AB: In your book A Brief History of Curating, you trace the evolution of the curatorial practice. What tendencies are you seeing when it comes to changing the role of the curator today?

HUO: If you look at the last ten or twenty years, the extinction crisis and the environmental dimension have become much, much more important. We are now facing a climate emergency, which means we need to come up with new models for how the art world works, especially when it comes to how dependent we are on travelling. In Europe we have the unique opportunity to travel by train, which could be a part of the revision. Then there is of course the impact of technology. I don’t think digital experiences will replace physical ones, because we need to see eachother now more than ever before, but I think technology will play a bigger part in how we meet in real life. Today the virtual and analog often meet in a kind of a mixed reality. In my opinion, technology often leads to alienation, separation and polarisation, and therefore face the challenge of thinking about technology in terms of a community. Alexis Pauline Gumbs once said: “We have the opportunity now, as a species fully in touch with each other [think social media] to unlearn and relearn our own patterns of thinking and storytelling in a way that allows us to be actually in communion with our environment as opposed to a dominating, colonialist separation from the environment.” Here we come back to your question about storytelling.

That’s what my exhibitions do. When they go to a city they learn from that city and they hopefully get better.

AB: How can a different approach to storytelling address today’s most pressing concerns? How is the curatorial practice a part of that?

HUO: I think that storytelling can create empathy, it can be a wake-up call. Storytelling is the production of reality. I think the potential in art lies in how artists always change what we expect from them. We should always be open to artists coming up with new ways of dealing with emergencies. Hope is important, that’s why we need new stories. Artists can make us imagine all these worlds, which are not here yet, the worlds of the future. Gerhard Richter says: “Art is the highest form of hope.” Society today needs that.

| Photography | Credits throughout |

| Interview | Astrid Birnbaum |