You Are A Thing

Published in Nuda:Terra

You could say that Olafur Eliasson, the Danish-Icelandic artist, was before his time when he started out his artistic career exhibiting a rock looking out of a window. No other artist has been as active in the conversations around the climate crisis. In fact, Eliasson has used some of his largest exhibitions in recent years to stage discussions around ecology and our relationship to nature.

With the theme of this particular publication in mind, Terra, it felt obvious that we would include a conversation with Eliasson about his art and how it’s driven by his fascination of humankind’s habitat. Ultimately, Eliasson’s artistic aim is to rehumanize us viewers. To remind us of some of the things we tend to take for granted; to wake us from our numbness.

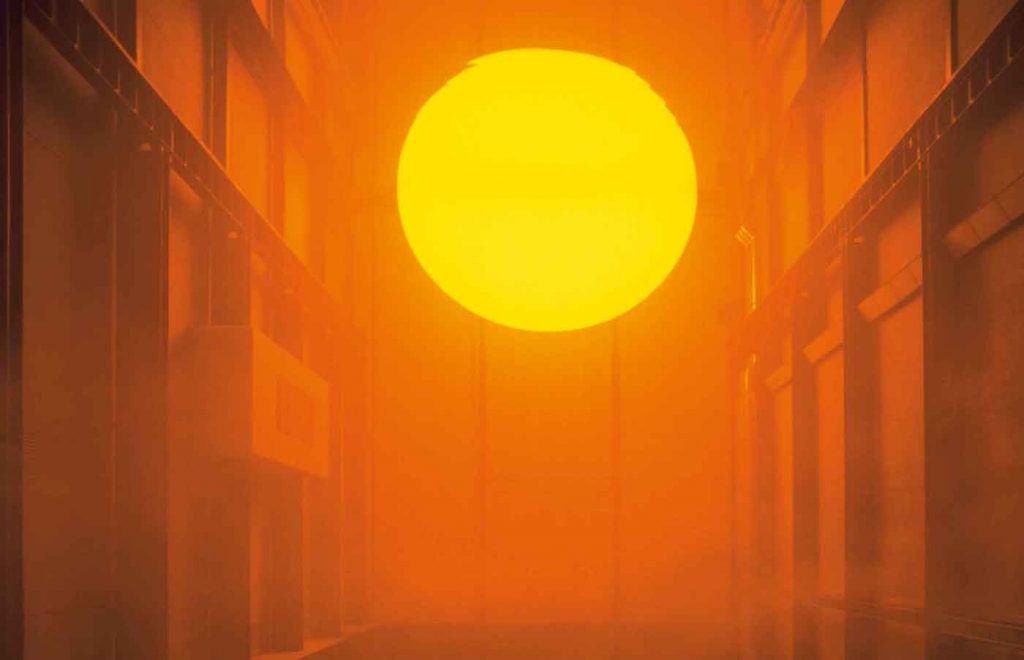

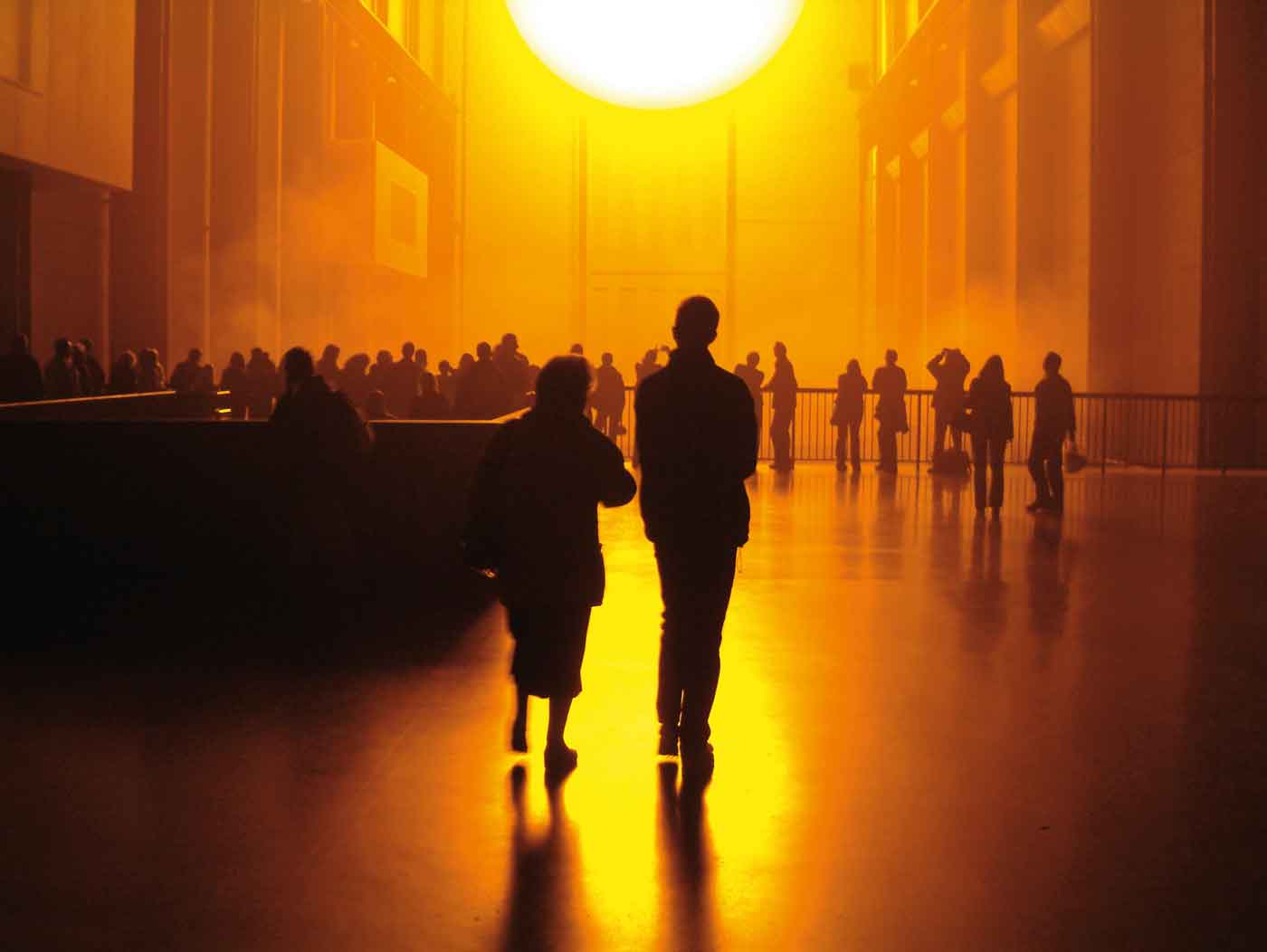

Eliasson’s art has been shown in the most important museums for modern and contemporary art all over the world. For a large audience, he became a well-known artist with the Weather Project at Tate Modern in London in 2003. To get to know his visionary practitioner, who today is visible across the globe, I sat down with him to talk about creativity and the significance of art in today’s society.

Astrid Birnbaum: Have you always been a creative person?

Olauf Eliasson: I started to learn how to draw as a child, all by myself. I was only three or four years old and my parents had just gotten divorces. My mother and father, both just 22 years old, lived apart and I only got to see my father occasionally. He would send me pencils, so in order to impress him, to make sure he would not run away, I became unusually good at drawing. I would say I learned to draw out of fear, the fear of losing my father. I think my parents were too young to see it at the time, but I was performing an emotional layer in my drawing. Later on, it helped me. Drawing was the one thing I was good at in school, because I was not so successful in school otherwise. I remember my dad used to make me doodle for 30 seconds on a page with a black pencil and then fill all the fields with colors. Sometimes you could find a cat in the abstract picture. Through that, he taught me to trust my imagination and the whole idea of the imaginary.

AB: So you started working creatively at a very young age. Did you find other ways to express that creativity before you became an artist?

OE: When I got into puberty, I started dancing. I got involved with hip-hop and other sorts of music, learned electronic boogie, the Mr. Robot, popping, locking and breakdancing. Dancing thought me a few things that I later realized were important to me. First of all, it told me about collaboration. We were always working as a team, a group and created narratives together. Secondly, it told me that I could re-render the quality of the space with my body – with my physical presence. Sometimes even by very small means, as standing on a piece of cardboard in the middle of the street. I would, for example, dance in slow-motion, which made the audience see, not just me in my dark sunglasses and white gloves standing on Strøget in Copenhagen, but the relative speed of everything else. Dancing made me comfortable engaging with time and space and understanding what one can do with it. Dancing is about the space, time, the audience, your group, and the relationships between them. The knowledge and understandings I gained from dancing is something that I’ve carried with throughout my career.

I would, for example, dance in slow-motion, which made the audience see, not just me in my dark sunglasses and white gloves standing on Strøget in Copenhagen, but the relative speed of everything else

AB: I know that back in the early 2000s, you were working from your living room by yourself. Today you have big studios with over 90 employees and your practice, at least as I understand it, is very based on collaborative work. For example, you have been working with scientist, engineers, and architects. What does collaborative work mean to you as an artist?

OE: When I went to art school, the first thing I did was to form a group with two other people. We called ourselves The Ventilators. We were probably quite arrogant, but we thought about ourselves as some kind of “fresh air”. Nevertheless, once I was done studying, I realized that there were quite a few things I was not so good at that other people were very good at. I wasn’t really interested in immediately getting people to work for me, it more reflected my lack of skills in certain fields. Money was one of them. If I had money, I wouldn’t make it last longer than one or two days. I was a very unhealthy person to be around because I would also always spend everyone else’s money very quickly. I say this because one often romanticizes the idea of collaboration. I just needed help, that was how it all started. The people I work with were so brilliant and smart, and that inspired and stabilized me.

I was very sad to discover that I was not such a good architect myself, but working with an architect, if it was the right architect, I had an enormous upgrade in skill. I am good at understanding and articulating something in space, occasionally. But an architect’s work is just amazing. I love the field of architecture too much, not to do it. Eventually, I started to have people around me who were good at all these different things, that I wasn’t good at myself. I ended up having so many people around me because there is a lot I’m not good at.

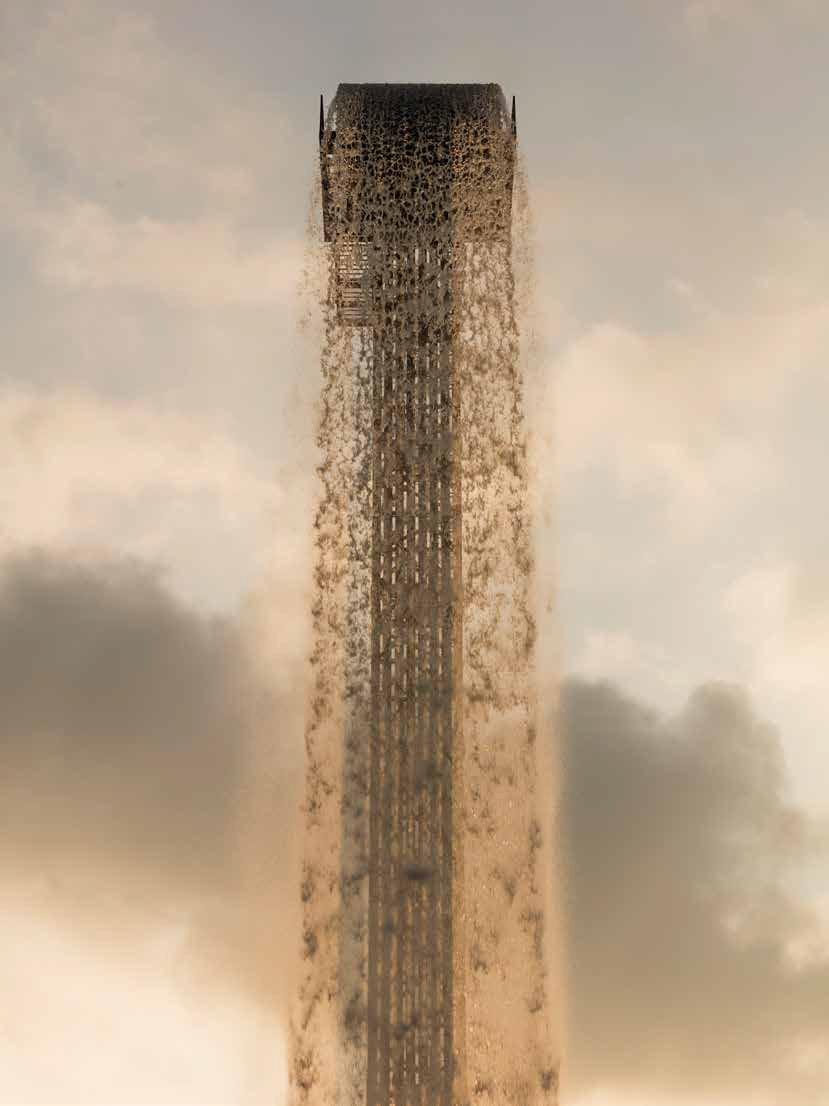

My studio is not a collective, but we are collaborating. I am the artist, and I am the only artist in the studio. But art doesn’t necessarily have to be made only by the artist, there can be other talents involved. Just by bringing in someone from the outside of the studio, one can make work that you didn’t think was possible before. For example, maybe I though something could just stand on one leg, then I bring in an engineer and they will tell me, “no, no, it will fall, you idiot, if you do that”. Collaboration has profound impact on all the work we do in the studio, but it is still me who is the artist, and what I do is art. I hope. Well, that is not an important question, there are no rules. If I say it is art, it is art.

I ended up having so many people around me because there is a lot I’m not good at

AB: You seem to have a special interest in the properties of light, how it contains different colors. What is it with light that is so fascinating to you?

OE: Well, first of all, I was very curious about the dematerialization of the optical. I was very interested in suggesting that the experience is constitutional for the work, if you are not looking at it, one could fundamentally question if it’s even there. Rainbows depend on an angle between the sun, the drop of the water, and the eye; which has to be 45 degrees. If you take the eye away, there is no rainbow. Light was an opportunity to examine the instability of the real. Light itself is only visible when it lands on something. On its journey from the bulb or the sun to the surface, it is not detectable. Rainbows are therefore particularly interesting because they somehow allow us to see what the light that is hiding and makes us see the fact that we are seeing. There is something in that, which I think worked very well in trying to argue for the interdependence of viewer and work. But light was also all very cheap. You just really need to go outside to find it, and that is not a bad start. Light is, of course, a natural phenomenon itself, and in all its glory and plurality light in nature is, of course, a thousand times more interesting than the crappy light we have in our houses.

I was, of course, very inspired by the west coast artists and the type of minimalism that then became Land Art. And the notion of early cinema, which was driven by light or Hans Richter, the experimental artist from Germany from the 1920s. Another inspiration was photography, Muybridge, who claimed to show time when showing a series of photos taken of movement. I was always less interested in the existential and how light was treated as proof of the existence of a higher force. I am an agnostic, or an atheist, or something in between. The point is: I was never really into light as a mythological opportunity.

AB: You gained recognition for works displaying nature or natural phenomena in different ways, such as melting glaciers, the moss wall, and of course the Weather Project at Tate in 2003. What’s your personal relationship with nature and how come the natural life of our planet fascinates you so much? How do you reflect on working with nature as a medium?

OE: I don’t normally think of nature as a medium. I am interested in using, or one might say abusing, nature to explore the relationship humankind has with its own habitat. Nature work really well to examine how humans and habitat coexists. The toolbox is vert big, so to say. There is almost nothing with nature that is not interesting. even a glass of water is like a miracle, it is unbelievable if you start to think about it. If we would think about that all the time, we would get so busy. Even the little side row of weeds, you know, the yellow little “pusteblume”, where you can blow the seeds out fascinates me. The purpose built into that little machine are so impressive, that even Volvo, including the entire factory, are by far not as interesting as that weed.

I am interested in using, or one might say abusing, nature to explore the relationship humankind has with its own habitat

I’m mainly interested in why nature can somehow convincingly create ways of investigating our sense of relevance and existence including morals and ethics. I love nature, I really do, but I’m actually interested in people. In humankind. People and animals if I stretch it a bit. There is an amazing quote: “Let’s start with the end of the world, why don’t we.” It’s by a science fiction writer called N.K Jemisin and the book is called The Fifth Season. It is about the whole idea of the end, that the world has to come to an end, start here and then go forward.

AB: I’m thinking about these early work with nature, such as the horizon works or Beauty. It seems like the discussion about our planet has changed so much since you made these works in the mid-90s. I mean the idea of global warming has really become a much more important question over the years. You lived it, so how do you reflect on the change of that debate? Have your ideas about these works changed? And has your approach in the working with nature changes as the debate in society over time?

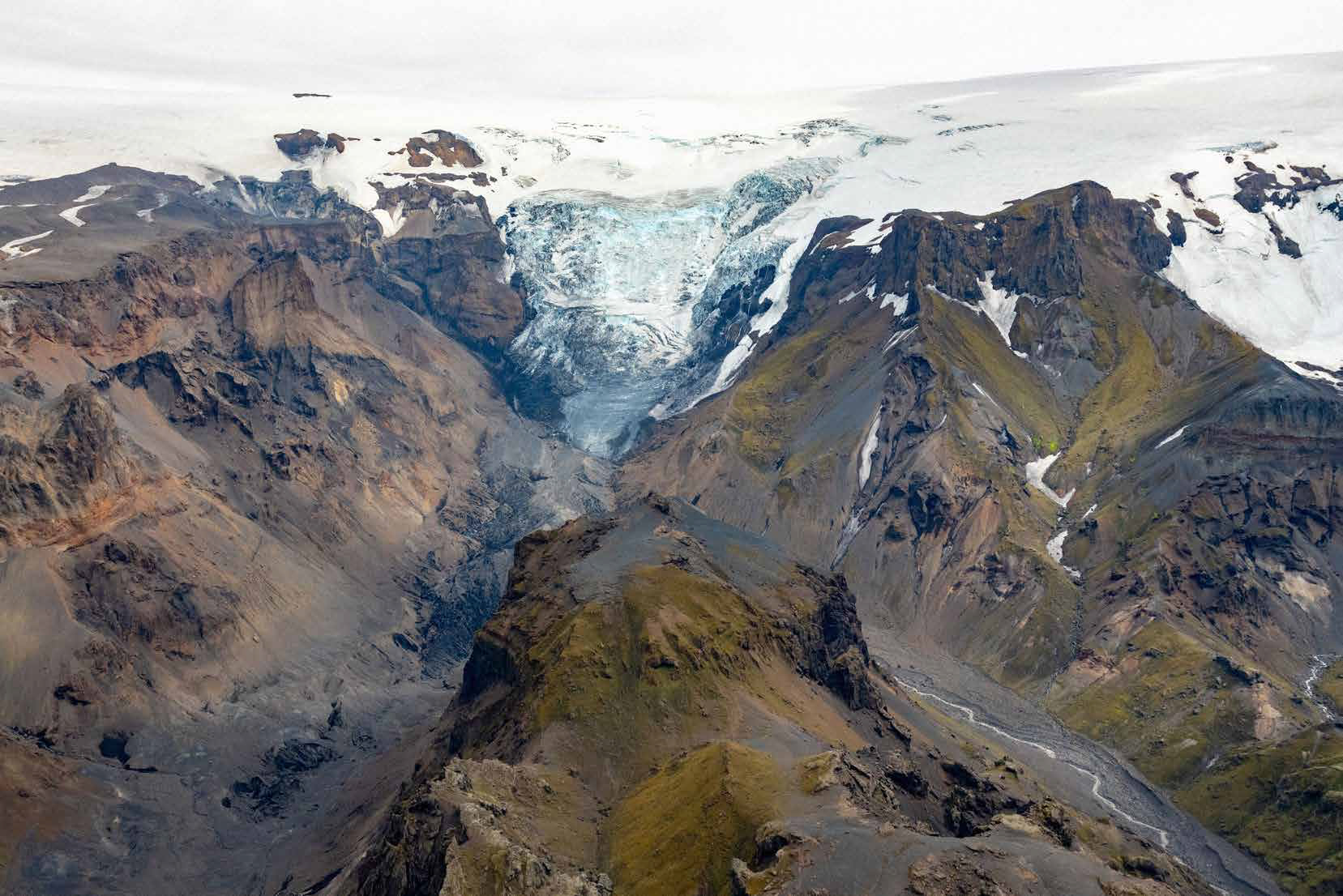

OE: All these works always had multiple and different implications for me. When I made the Weather Project, it was as much about the notion of a shared atmosphere, as it was about revisiting the construction we call “the weather”. For example, the way you talk to a taxi driver about the weather. It is a good icebreaker as we know, a funny word to use here. I had made pieces using water, light and I even used ice in very early works. I started to become conscious about the notion of nature bing culture by now since there was nothing that hadn’t been touched. At the time of the Weather Project I also, for the first time, came in contact with different environmental communities, and the early terminology for greenhouse gases and global warming was starting to appear. Back then, it was also disembodied and abstract, it was all about numbers: degrees, time, how long, how much money, so on. The discussion never really became about humans, or to be shared and understood by the general public. I knew that one only had to go to a glacier to understand. But the problem with that is that when you’re on the glacier, the glacier is very busy “glaciering”, and it has its own intention. It kind of becomes weird to stand there and say: “now my theory is embodied”.

There is a half-truth in that which I believe in, and that is that looking at nature can challenge our numbness. It pays off to go to the forest, to look at the grass and the flowers, it pays off to look at the stars at night. We are all numb in today’s society. I have become so numb that even when I look at a beautiful wooden table, I don’t see the tree in the forest anymore. This is a Lovelock thing of course. It is still a tree, the wooden table, it is not growing or going anywhere until we throw it out, and it becomes earth again.

looking at nature can challenge our numbness

AB: I’ve understood that you have been influences by the work of James Lovelock and the Gaia Hypothesis, is that correct?

OE: Yes, or I think the principle is what I’m interested in. The sense of interconnectivity and our failure in not acknowledging the crust on this planet, as this common space where we all have to thrive and live together with the plants and other species. He was so early in articulating it to that extent. I don’t subscribe to the thoughts of the whole idea of the motherly earth, and so on and so forth, it’s just not so interesting to me, but the notion that it’s a question of networks, fascinates me a lot. Lovelock has this holistic way of seeing everything as influencing everything. I’m also interested in Humboldt, and the way he would argue that natural science and poetry cannot be separated. Arts altogether, and science, botanical science, humanism, why separate them into these categories? And Goethe, for the same reasons. More or less all romantic thinkers would somehow subscribe to the idea of interconnectivity or the dynamic symbiotic state of things.

I think we have lost the thought of being part of nature. Instead, we have been collectively traumatized and become numb. We think of “being outside” even though there is no outside. Really. Unthink numbness. It is because of the numbness. call for the “need to rehumanzie”. The need to somehow become human again. The Paris agreement report, the report of the planet’s health, is the most important piece of writing ever. I mean the Bible and the Quran have had some significance as well, but this report is uniquely important. If we cannot translate it into something physical, or into something emotional, and acknowledge our feelings, then I think we are not going to be able to react fast enough and we will push our planet beyond the point of no return.

Even though I believe we need to react with feelings, I also want to be cautious about not only being emotional about these problems, because I think that can be dangerous as well. If you take science away, well, then you have Trump. One big messy emotional piece of junk. It’s not even junk, it’s worse than junk. I think we have become zombies, I don’t know how to say it better. I don’t have the answers and I’m not sure if what I’m doing has an effect as such, but I feel quite good doing it, and I think that’s enough. If I can just be a part of the discussion, I don’t need to solve the whole problem. I do not feel that I have to come up with an answer, I do think it is worth collaborating. It is not about competing, it’s about collaborating. Sadly, one of society’s Achilles heels is that it is very competitive.

the problem with that is that when you’re on the glacier, the glacier is very busy “glaciering”, and it has its own intention

AB: During the later years your art have not been reserved for an art crowd one can say. Some of your projects move over to social projects, trying to change society in different ways – connecting people through art. Do you believe in art as a way to create change in society? Do you believe in the power of art to change the world?

OE: The answer is yes! So that was a quick answer, right? No, so normally I don’t think of a binary balance between change versus no change. I also don’t think it’s possible to say: “OK let me just take a step back and look at the world from outside”. I’m not “outside” of the world putting art into it. I see myself and my art as part of culture. And being a part of the world and society always has an impact on the system however small or big. So I think there are two kinds of answers to this question: one macro and one micro. The civic society is kind of made up of different groups or sectors that are attached to each other. One of the big parts is what we could call the culture sector. This is part of our society that thinks about society itself and evaluates the values we live in by and our humanistic ambitions. As time goes by, it turns out that some of the values we live by are conservative and we want to be more progressive and change them. One of the great systems that somehow pushes that thing ahead is culture. Another one is education. Even economically closed systems like capitalism, they push ahead the market economy. Society is highly dynamic. And the civic society, I think, relies on the success of a cultural, qualitative, critical mass.

AB: So, again, what’s the role of art?

OE: As an artist, I am conscious of participating in the world. It’s my responsibility, and it’s an honour. It is honourable to be in the cultural system because the values are not based on economy, they are based on art. That is something quite unique. From the micro perspective, art hold the opportunity for something incredible, like revisiting your own most intimate or most private, yet not solved, ideas. I’m not saying this is what defines culture, I’m just saying it’s one of many opportunities. Once you visit a cultural opportunity, looking at a theatre play, looking at a work or art or something like that you can reach that degree of intimacy where you are taking your cognitive self and somehow live it through your body.

There is this incredible idea about your presence in the world, which is not just an idea, it is a physical question. And in that question, you suddenly are in a safe space. And the painting on the wall reaches out to you and listens to what you have to say. So it is like the painting is looking at you, it’s hosting you, I could say, holding your not yet articulated emotional need to be recognized. There is such a profound physical sense of inclusion from culture to say to you, I hear you, I see you, I meet you, and you are good enough. You are a person and you are a part of something. It might not be easy to explain, but you are experiencing this moment. Being a part of something where you feel you are not useless is such a valuable thing. Feeling that somebody for the first time fucking listens to you. Making you understand, “I might just be ok.” You are a thing.

Art hold the opportunity for something incredible, like revisiting your own most intimate or most private, yet not solved, ideas

| Interview | Astrid Birnbaum |