A studio visit, Toki, Japan

Born in Hiroshima in 1981 and based in Gifu, Takuro Kuwata is a Japanese free-spirited ceramicist, well-known for his stunningly vibrant pottery, often coated in thick metallic crackled glaze. Kuwata currently works from his studio in Toki, which sits on a large clay basin in a rural city, not far from Nagoya, known for some of the greatest producers of Japanese pottery.

His traditional education and mastery give him the freedom to bend and test the rules of clay. Experimenting with the limits of this material results in serendipitous works. Kuwata punctures holes into his large pots, layers on extra-thick glazes, and creates works that seem to come alive from the kiln. Each work is bold, daring, and pushes the boundaries of what contemporary ceramics can be. Whether it is his exploration of spiked and speckled textures or large forms extruding from his pieces, his unique perspective of the new and old as a highly-skilled artist makes Kuwata’s work truly exceptional.

His works take influence from the Japanese tea ceremony tradition, Sen no Rikyu, or the Japanese “way of tea” and the wabi-cha style and are all unique and functionally beautiful. In the manner of a tea ceremony, he politely pours us some drinks, we discuss his work including the cups the tea was served in. From his color choices inspired by Italian furniture, to explaining his favorite exhibition at the Tate Modern and his deep love for 90s hip hop, he surely has a deep understanding of culture – not only of his own.

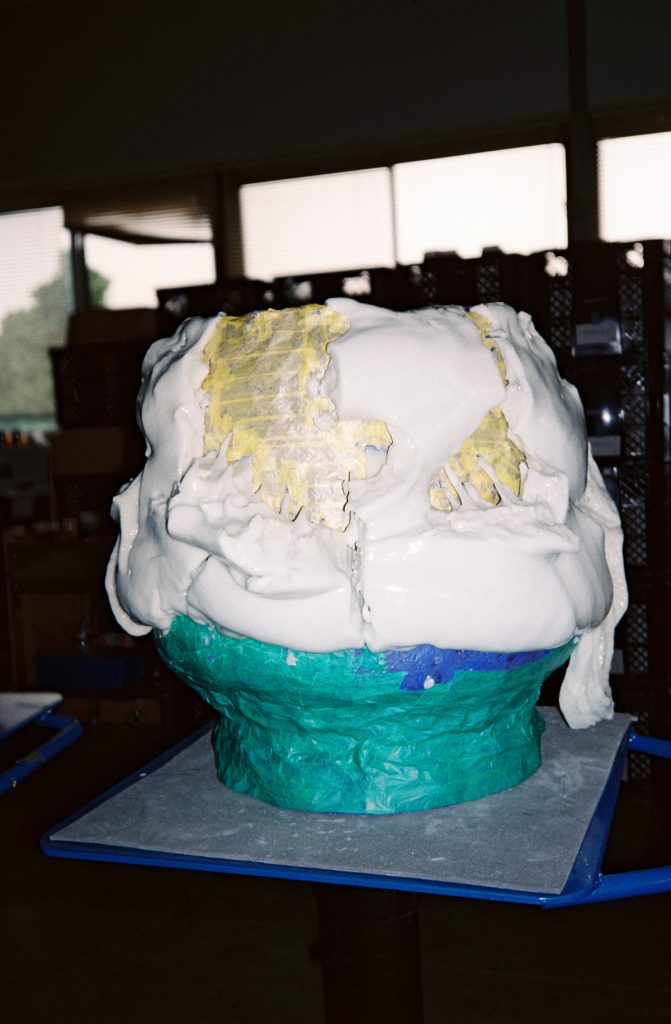

Twelve or so large vessels are aligned on the first floor of his studio, which are all in the masking process before a second glaze. They are coated in a selection of bubblegum pinks, bold yellows, and mint greens, ready to be overlaid in gold. The taffy-like texture of the pots shows off his playful attitude in experimentation. These works, once finished, will be shipped off to Paris for his upcoming show.

Kuwata jokes that the top floor of his studio is a grave of past projects, but there is nothing but new life there. Rows and rows of radiant, warped, trial and errors which have a story of their own. These are the works that exploded in the kiln, dripped out of shape, wilted out of balance, and found their home on the top floor. He uses these as inspirations for his upcoming works, or even takes an old piece to rework. With graceful ease, he explains his “mistake” works, pointing out certain ones, and thinking out loud that maybe some weren’t that bad after all.

As a proud export of Japanese culture in a global realm, he is not only extremely talented but also manages to create the perfect synergy of the traditional and modern. His modesty, wonderment, kind-spirit, and transformative views add himself to the canons of contemporary Japanese artists that can be enjoyed on an international platform.

Anton Alvarez is a Swedish-Chilean artist currently most known for this colorful and playful ceramic sculptures. His self-constructed 3-ton strong ceramic-press, The Extruder, squeezes wet clay through different molds to create unexpected shapes. The process is somewhat half man, half machine and the moment of creation is merely 3 seconds. As two artists pushing the boundaries of ceramics, Takuro Kuwata and Anton Alvarez are long-time admirers of each other’s work.

AA: I understand that your studio is situated in a part of Japan where the tradition of ceramics is very present. How has that affected the work that you do and how do the traditionalists around you receive your work? What are your thoughts on reworking tradition? You’ve been making tea bowls for a long time, what’s your relationship to this object?

TK: In order to deepen my knowledge of ceramics, I moved and started working in the Gifu Prefecture – the center of historic tea ceremony ceramics production. As soil can be easily extracted in this area, it has long been a place of ceramics production for both industry and artists. A tradition in itself is made up of both the tradition to pass down a technique, along with the tradition of inheriting a will or a purpose. Some tea masters and traditionalists, that have understood my sentiment, have shown me many invaluable historical artifacts over the years that have been used in tea ceremonies. They have also taught me the historical background of the tea ceremony as well as the values tied to the art. This is how the tea bowl became an object of inspiration for me, as well as a subject of my work. I think it can be a good thing to continue to mediate the old traditional techniques while simultaneously creating new traditions according to what is possible in today’s technical era. I was once told by a tea master to make sure to “deliver my work without distorting my initial expression.”

AA: In my own work, I really appreciate when something looks like a force of nature, rather than man-made. I want it to look like it made itself. I see that a lot in your work too, and that is probably one of the reasons I really like what you do.

TK: When looking at my work process in an overall sense, it appears as though I have full control over everything. However, when looking at each part of the process on its own, it’s not just me exerting my will, rather, one could say that I am facing and keeping a dialogue with the materials. From this dialogue, I try to find and bring forth some sort of answer. For example, creating with intention might mean to purposely set a range without controls – to test the limits of the material or to search for the fine line between failure and success.

AA: I often find that unexpected results can inform a new way forward. What does failure look like to you?

TK: When I have experienced failure in my work on a visual level, it has been at times when I wasn’t able to find a way to balance the harmony between the process and the materials. However, through these failures, or the times when I can’t decide whether something is a failure or not, there is always a chance of inventing something completely new. It’s a matter of being prepared and ready for this chance when it appears.

AA: Ceramics is one of the most durable mediums humans have mastered, but at the same time it has a fragile nature. When excavating a prehistoric human settlement, ceramics are usually the artifacts that are best preserved both when it comes to shape and color. Your work has a bright and powerful presence as a whole but when observing it from close one can discover more layers, such as a small intricate detail made of a fraction of a millimeter thin string of glaze. For me, this represents a beautiful combination of power and fragility. What is your relation to the dual aspect of fragility and eternity in ceramics?

TK: As you said, ceramics possess a very fragile nature, but on the other hand you could say that it is a material that, in spite of breaking into shards, will last for thousands of years. At times I go to look at excavated ceramics at museums, these uncovered pieces and fragments provide us with information and the means to create an image of a different time in history. Seeing this makes me reflect on what I should be creating next. For me, the medium of ceramics was something I came across by chance. However, having encountered this medium of expression I feel incredibly happy for the various meetings that the art of ceramics has led me to. I feel excited to think that my own work might lead to the birth of something else, something yet unknown.

AA: You are unquestionably a master of the medium of ceramics and especially the chemistry of glaze. You have a whole part in your studio with fired objects that are neatly lined up on the floor. Does this way of placing out unfinished objects on the floor serve a purpose for your practice?

TK: The objects lined up in my studio are ceramics that never became finished products. Instead they have become a collection of their own, made by the traces of my past dialogues with materials used in the work progress, much like an album of memories. By looking at these objects, I can clearly see the dialogue I’ve had with my ceramics. They become valuable objects that convey information of both technique and a kind of spirituality.

AA: I heard from a mutual friend of ours about your interest in hip hop, and more specifically breakdance. Does this still inform your work or life in any way today?

TK: In high school, I spent a lot of time dancing in the streets together with my friends. I just enjoyed this feeling of losing myself completely in something. Dancing was just one of those things we did for fun. I don’t think dancing has any direct influence on the work I do today. However, I think that type of interaction with friends gave me a subcultural perspective from which I naturally look at the processes and materials of ceramics. In that sense, one could say my hip-hop years still have a great influence on my current work. Nowadays, I listen to almost any type of music, but since I went to high school during the 90s, I still listen to a lot of hip-hop and R&B from back then.

AA: According to the traditional definition of hip-hop, it could be divided into four elements – DJ-ing, rapping, graffiti, and breakdancing. Perhaps one could do the same with the components of ceramics and its process. For instance, it could be earth, air, fire, and water? Or clay, glaze, fire, and … luck? I understand that your process centers a lot around your complex and highly advanced skills within glaze and your knowledge of the fire process. Is there any part of the ceramic process that is more important than the other for you? Or could one thing not exist without the other?

TK: These last years I have been very inspired by the Japanese tea ceremony. Being in the mindset of the tea ceremony, I find that something can only take form once you find the moment of perfect balance between two of the values connected to the practice of the tea ceremony. The first one is the understanding of the history and spirituality surrounding ceramics at different points in time. One needs to understand each object’s historical background. In the creating process, this means actually feeling and getting to know the materials and the traditional techniques. The second one is about sharing the values of the tea ceremony through encounters with people inside the community. Ever since becoming aware of these two perspectives and feeling moved by these shared values in the art, I have been searching for that perfect moment of balance between them.

AA: I come from a non-artistic family. When I grew up I didn’t even know one could work as an artist and I had never met one. Instead, graffiti culture and painting illegally in the city became my introduction to art and was the starting point for my creativity. Later on, I had to take a break from it for different reasons and because of that I applied to art school. How did you find the path of becoming an artist? Was ceramics your first medium or was there anything else?

TK: Just like with graffiti in your case, I used to go out a lot at night to dance and listen to music. I especially liked dancing and even considered going to a dance school, but since I loved both painting and crafting since I was little, my desire to go to art school won in the end. Pottery happened to be one of my specialized subjects there, and it was the teacher of that class that taught me about the avant-garde pottery style. Somehow, however, I couldn’t quite get accustomed to the school and ended up not attending lectures, wandering around nights on end instead. It wasn’t until after graduating that my big turning point came when I was brought in as a disciple to a potter. Here, I was taught all of the basics related to the ceramics of the Japanese tea ceremony, of raw materials such as soil and glaze, and of processes such as firing. Reflecting back on that time, I think I experienced that same feeling of excitement in losing myself completely in something that I had experienced earlier in life through dancing.

| Interview | Peter Sayn-Wittgenstein |

| Photography | Anton Alvarez |

| Intro | Yurina Roche & Peter Sayn-Wittgenstein |