In conversation with Sophia Al Maria

The sun is a camera

Published in Nuda:Ego

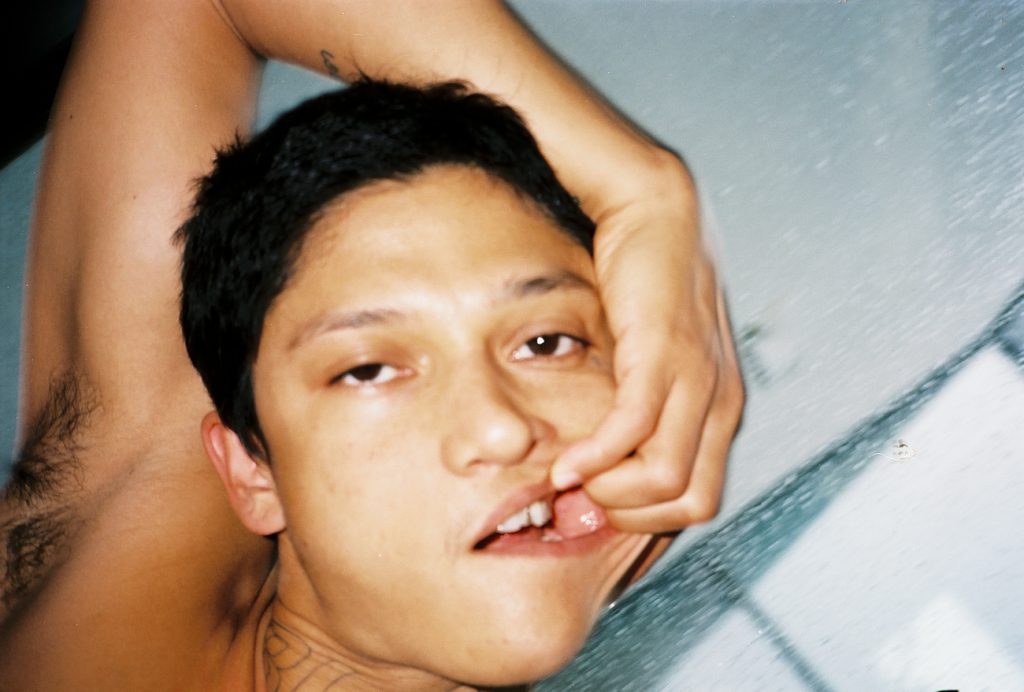

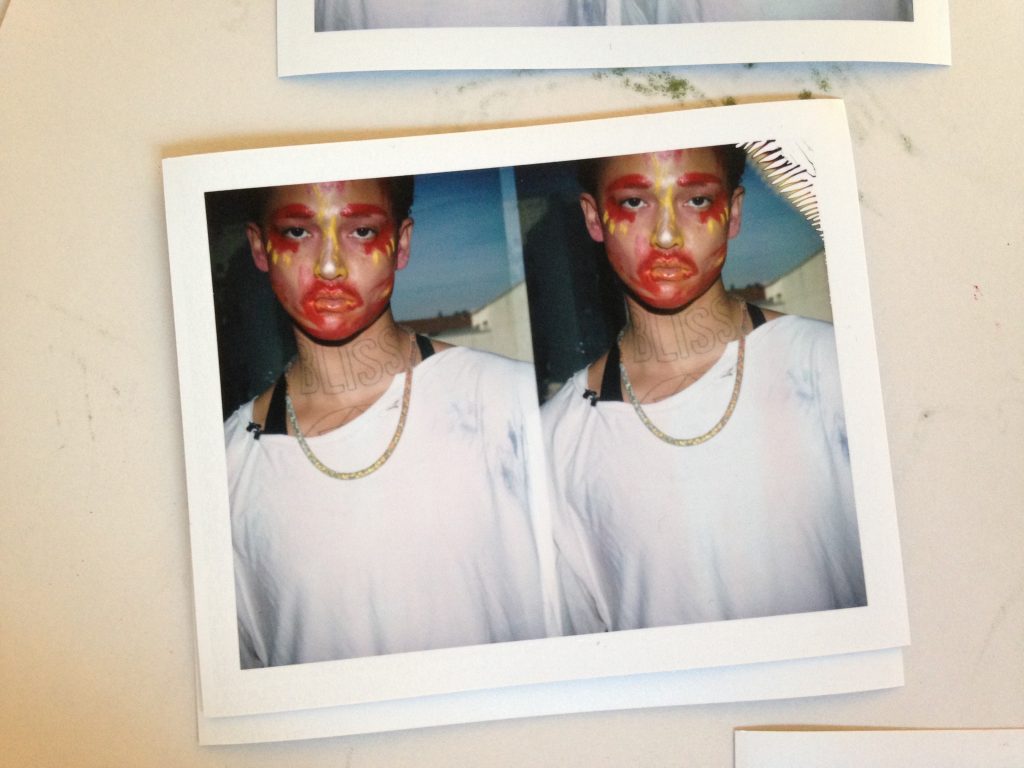

Artist Tosh Basco, formerly known by the moniker boychild, has been seen, looked at, admired, observed, perceived, and noticed by countless people over her career. Her performances—an ethereal communication of body, sound, language and light—have been presented at numerous international institutions such as MoMa, Gropius Bau, and the Venice Biennale. Using photography she explores desire through multiplicitous, fictive, and fissured notions of self. Basco discusses her latest series of portraits in a detailed conversation with her close collaborator, artist, writer, and filmmaker Sophia Al Maria. Here, the two creators explore the ungraspability of the ego, and all the ways in which we see one another, and ourselves.

ETEL- TIME XIII

The self is an image of an image

…Where are we?

For nearly two decades I have photographed myself. It is somewhat through this practice – a reflected, refracted and refused trajectory- that i finally arrived to an improvisation performance practice under the moniker ‘boychild’. Photography taught me many things about the frame. The process taught me the alchemy that can entangle itself within the edges of an image. How lines of visibility (what is seen and what is NOT) create a scene or conceal it. Photography too taught me about the micro and macro implications of image making, the power structures of seeing, the fluidity of subjectivity and how it is reigned in and on through the extensions of subjectivity into subjecthood.

Before the selfie, I had a long standing relationship with self/portraiture. My father who was a photographer, taught me early on, a sense of how to perform when he would take my portrait. As a child I knew how to hold a gaze, how to find the light, how to frame and be framed. When I was 13, he gave me a film camera like his. That is when the explorations of imaging my self took root. It is the practice of self-imaging that has revealed the fiction of a fused self. I learned instead the ways in which the self is indeed imaged, through language, through performance, through gender, through law. My self-portraits now are markers of that fluidity and simultaneous discomfort, almost a rigidity I have with my own gaze. It is the quiet antithesis of my performance practice that is free, that is collaborative, that is never fixed and always moving. It is a sitting with my own desire toward something that feels close to death but has no words. It is a way for me to face a kind of violence that is inevitable in looking.

The self portraits are a report that there is an ego somewhere in constant ‘shatter and embrace’ flaying out toward splendor in its own inevitable disintegration.

– Tosh Basco

Sophia Al Maria: Talking about ego reminds me of that Etel Adnan book, There: In the Light and the Darkness of the Self and of the Other.

Tosh Basco: Etel’s words are so visual. I remember that line, “the sun is a camera that operates only in black and white.”

SA: Yes! And “white white white is the color of terror”

TB: All things visual somehow connect back to Etel’s Sun. When I think about photography and ego, I think about seeing and looking–about mirrors, lenses, cameras, and eyes. I understand this drive I’ve had toward windows, mirrors, frames and their relation to my performance practice within my desire to take photos. The terror and the desire touch within me in a very particular way when I take photos. Not like performance. With the photos it feels like an exposure of some dark or hidden desire. I think of quote of James Baldwin that Fred Moten evokes in his book All That Beauty: “About my interests: I don’t know if I have any, unless the morbid desire to own a sixteen-millimeter camera and make experimental movies can be so classified”.

Baldwin calls it morbid, I associate some kind of visceral feeling of terror of the unknown.

SA: Driving towards windows makes sense, it’s like the blind mirror, or others seeing in. The eye has a lot to do with evolution. Artists evolve through the eye and seeing—looking at the self or the work they’re doing. I’m looking at your photographs. I love them. Would you categorize them as selfies?

TB: No, No, I would say some of them are self portraits. Some are portraits of me by those that I love. To me this collaborative process is a way seeing through each other.

SA: I paused on one I’ve never seen before, and had to do a double take. It’s an over-the-shoulder shot into a mirror and you’re blonde. It just looks like a completely different person from the back.

TB: That was right before a performance I did with Ron Athey in Austria. I wouldn’t know that I look like a different person, as I’ll never see myself from the back. Like how I’ll never see myself perform. The first self-portrait I’ve ever taken—I don’t think I have it anymore—was a black-and-white photograph. I was reflecting on the impulse to photograph myself, initially it was this impulse to make sure I was there.

SA: Since you don’t have that image and you’re starting to put together a language to your photographs, can you describe that photo?

TB: It was a 35-millimeter black-and-white photo. There’s a different quality to film when it’s black-and-white. You can feel a physicality of the chemicals that danced with light in order to make the image. I had a shutter release cord in my hand. It’s funny that you brought up selfies because the cropping was a very similar framing: the bust to top of head, one arm descending into the bottom corner where the body physically connects to the camera aparatus. I know I was 17 in the photo because I cut all my hair off that year. It might have also been something I took for an assignment. I was still in highschool but I was taking photography classes at one of the local colleges.

You’re one of the few people I photograph, and one of the few people that photographs me. You wrote a memoir at a very young age, not in relation to photography, but on imaging of the self as a young person. Is there a convergence where those things are tangled or run parallel? What were the different ways of shaping the narrative, and how is that similar to image-making?

SA: There is so much in an image that could never be unfurled in a thousand memoirs. You’re probably familiar with this anomalous thing that happens when you can’t remember if something is a memory or if you remember it from a photograph. There’s a real link to your question in that memoir in particular, The Girl Who Fell to Earth, because an old leather suitcase full of photographs was the material I used to write from, as well as interviews with my family, and then later in the book, my own memories.

The very first passage in that book is about a camera. It’s about an experience that my father had with the other end of the camera, watching television and being a consumer of the image. He falls in love with Syrian singer Samira Tewfik, thinking she was looking directly at him, but she was just looking into the camera lens. It’s an imagined scene of an unnamed director coaxing the subject to look into the camera and that gaze back into the camera being this explosive force of love for many people. I do think that’s something that happens sometimes when there is contact made, and in particular in self-portraits.

TB: That contact is incredibly powerful. One word for it is ‘gaze’ which can be reciprocated, dispersed, and transferred. It’s interesting how an energy can be passed through, the mechanism of the lens of the camera even if it’s also kind of severed by it. I’m often asked about my performative practice under the name boychild, and how it’s related to photography. I learned how to hold that gaze as a child because my father was a photographer and he photographed me a lot over the years. Learning to return the gaze at such a young age was especially informative to my ability to hold the energy of an audience.

SA: Do you think that’s something which can be learned?

TB: Yes and no. We all have proclivities towards certain skills or talents I intuitively found mine for various reasons. Survival reasons mostly.

SA: That makes a great deal of sense.

TB: Humans are very sight-oriented.

SA: Well, we’re predators, aren’t we? I think that sort of individualism or ego is very much something that happens in predatory animals.

TB: I’m not sure. In considering this theme, ego, I immediately gravitated towards photography and the photographs I take of myself, where if I continue with your metaphor, I’m both predator and prey. So much of my work and collaborations have been about seeing and looking, and also about the negation or refusal of how we are taught to see, a refuting of how we are taught to make meaning through sight—the kind of frameworks that performance shatter. The ego feels like a reflective surface, like it’s not real.

SA: There’s a sort of ungraspability around ego. I don’t know much about psychoanalysis but I do feel that the mirror, the lens, Narcissus—unfurls infinitely backwards.

TB: Would you say that your memoir is related to photography?

SA: Most of my writing is either music or photography influenced. I can riff off of an image endlessly. The first thing I ever wrote was in response to a piece of footage I saw in 2001 of a Palestinian kid who was killed in his father’s arms. Journalistic photography is kind of the farthest you can possibly get from a formal self-portrait, because it is ultimately othering—hyper difficult and problematic in so many ways—but it’s also up there for me with comedy. I know that sounds strange, but I think both comedy and photo-journalism are incredibly difficult feats. One is generally performance and the other is an observation.

TB: They are attempting to move towards the truth.

SA: Yeah, they move towards truth, and so does the self-portrait for that matter. But it’s impossible—as you say—to see the back of your head, and it’s definitely impossible to write with any objectivity about the self. I know I’ve completely given up on the idea, even though I started in journalism where there is a myth that it’s possible. Do you place any value on the idea of objectivity in your work?

TB: I value process. I value questions as answers and collaboration. I have come to value the feeling that I don’t know how else to call other than terror, especially when I’m making work. It’s a different kind of terror than Etel’s, or maybe it’s the the same in a different manifestation. It reminds me of tinnitus, a small but piercing sound that only you hear: it is still gravitational but not visual. It sonic, you move toward it.

These photographs and the process of taking them, reveal to me the impossibility of a singular or fixed self. Many people speak very different photographic languages that can tell many stories and truths, as well as beauty and horrors. Mine is almost this bland and persistent desire that reveals almost absolutely nothing

[laughs]

I think this is where my ego lies. I’m constantly making sure my shadow is still there through these photographs, and these photos remind me that I’m definitely not there.

SA: It’s terrifying to look deep into the shadow and see nothing. Suddenly, looking through these [photos] is different, as if something has deepened in them. As a person who is not you, looking at the images feels fractured in some way. There’s a sort of pattern recognition that I’m experiencing—like a chrysalis of image and of a person in the process of growth and evolution.

TB: I have a desire to disappear in a way, but maybe I’m too afraid.

SA: That desire reminds me of the way Ajit Mookerjee writes about creativity in his Yoga Art and Tantra Art books we read during lockdown. It’s such an old human urge documented in those works. To be one with everything and evaporate the self.

TB: Yet, here I am with all my selfies.

SA: Ha. But your selfies are some of my favorite public artworks. One thing I’ve experienced in your performances is a feeling of almost dangerously inverted openness—some quantum level portal opening. It feels like you can’t do that if you’re holding on to some kind of membrane of self.

There is a certain way in which I encounter the world being a trans person of color. Certain encounters make me wonder what a person sees in me.

TB: Definitely not. The photos are the inverse of that. They’re performative veneers. There is a certain way in which I encounter the world being a trans person of color. Certain encounters make me wonder what a person sees in me. When I look in the mirror, I don’t know about you, but I don’t see my self. I can’t understand through the mirror or sight alone. I don’t ever feel like I experience seeing myself, and I think a part of portraiture is about fixing it so that I could try to see in this way. Maybe there’s something an image could tell me. I’ve long learned that it’s not the image that will tell me anything, it’s its own failure, it’s…

SA: The reaction to the images. You stand behind the audience and watch what they see.

TB: What do you mean?

SA: It’s an attempt to understand the violence of the way people look. One way to do it is to place self-images in front of them and stand behind them. It is a strong statement to attempt to do that, especially when someone has been imaged as much as you have by other people. And by people who have exoticized or fetishized you.

TB: Maybe that’s why they’re so dry. I was trying to search for the most non-exotified images of myself. I feel like I do that all the time. It’s become a thing I feel more comfortable employing—those fine lines between desire and portrayal. We’re kind of where we started, in thinking through looking and seeing, and thinking about perspective and visibility, about memory and tracings.

SA: I don’t know if you remember the first picture I ever sent to you, of me sleeping with a baby goat and you can’t see my face. I dug that back out again recently because I was asked to do something in a project around animals and costumery. I thought about how I would have never been comfortable showing that to anybody a few years ago, but now I don’t see it as a self-orientalizing thing in any way because it’s just the truth. There is a pleasure and freedom in not showing your face. Being unphotographable and unidentifiable is something which I think especially the West does not understand, and the camera definitely doesn’t understand. You have only to take a photograph of a woman in a niqab, or think of the perennial frustrations of people who don’t know how to photograph Black skin. That’s a huge question around photography—the way chemical processes and everything can just erase.

TB: The paradox of that is violent and astounding. Photography’s historically racist, its eugenicist impulse is never not there for me. But also, what you’re saying about niqabs… I don’t by any means know what that feels like, but I was laughing to myself at the ways I’ve been imaged over the years by other people, especially when I was performing as boychild and using a lot of makeup. For a long time, not many people knew what my face looked like without it and I really loved the anonymity. Makeup obscured my identity. I’m continually interested in the ways different people encounter similar experiences, and different ways of concealment especially around exposure of the self.

I’ve been really shy to show my photographs, I think due to the mundanity and banality of them. The flatness and the fact that I’m always naked. I was very self-conscious about them being just me by me. It’s a very difficult process, especially by the means in which I do. For me, performance belongs on the stage, whereas I don’t find photography as being something performative on a personal level. I take the photos when they need to be taken, or when I feel like they need to be taken.

As somebody who is very reluctant to be photographed, why am I allowed to photograph you?

SA: I think about this in terms of my relationship to the camera, because I grew up with a sort of opposite experience, where I was discouraged from being on camera. Whenever there were photographs taken, it was just sort of constant disappointment from the photographer, even in family photos. That’s when the question of vanity, or awkwardness came in for me, and not feeling fully centered or comfortable in the self. Fundamentally, as a person who also images other people, one of the things I really notice in performers or people who are photographed for a living, is that there’s this groundedness. I think that’s also why white people like to photograph indigenous people all over the world, because there is something they don’t have. I’ve only started to feel grounded in myself relatively recently in life. I guess it’s something that everybody probably feels to some extent, but I think it really shows in photographs of me and I’ve only really settled through trust and love. I think it’s because you’ve earned my trust.

In Western society, we are already integrated into a fractured sense of the self, with the ‘I’ and ‘you’ subjectivity

TB: There are many cultures in which they believe that when taking a photo something else, other than the image is taken too. We are taught at a very young age linguistically—also now through phones and photos—that the self is individuated and in opposition to the other. In Western society, we are already integrated into a fractured sense of the self, with the ‘I’ and ‘you’ subjectivity. It’s almost through the multiplicity of that fracture where I have become more grounded. I feel like I leaned into it so far that it almost disappeared, with performance in particular.

SA: The ego disappeared?

TB: Everything disappeared. All of it. Anything related to me and myself and you and yourself—any boundary. Beyond porousness. Particles touching rubbing dancing. I feel like people experience that all the time through sex or euphoric experiences of bliss, drugs, being at the top of the mountain peak, or through food or music. That expression of losing yourself.

SA: Yes. Losing yourself. I love the idea that it’s possible to lose yourself or that somehow that’s an antidote to the violence of being looked at.

TB: Yeah, that’s why I was wondering why I take these damn photos. They’re little strings to bring me back down.

SA: When you were talking about your teenage self taking that picture, it reminded me of the act of pinching yourself to make sure you’re not dreaming or to make sure that you’re here. The time period in which I’ve known you has been a really big dismantling of my previous foundations, alongside my previous understanding of myself and what it means to be in relationship to others. All of that roots deeply down into the culture I come from, which is such a formative part of me. It’s also been very freeing to be photographed by you and to recognize myself in a photograph for once, which rarely happens. I think that only happens through an act of love, and an act of seeing instead of looking—which I’m really grateful to have experienced in this lifetime.

TB: That’s really beautiful. I can be so stoic—not pessimistic, but critical. I’m constantly breaking down what it means to look and to see. But there’s another side of that, which is what it feels like to be seen. It’s such a powerful feeling. It’s not something I can do in portraits of myself. I don’t think I ‘image’ other people when I photograph other people. I try not to.

SA: It’s true, you don’t take casual photographs of others. But it’s become so casual with our devices, and the fact that you’ve resisted that is really special.

| Editor | Katrice Dustin |