By Barrett Avner

“To take the view that all myths follow the same pattern and that consequently a single key can unlock every one of them clearly reflects an unrealistic desire constantly to ignore differences and to reduce the many to the one; and here, to take shortcuts where none exist.” – Roger Callois, Le Myth et l’homme

The first known christening of the conspiracy theory was used as a pejorative – its first canonical usage was by the CIA to discredit critics of the Warren Commission’s handling of the JFK Assasination. The etymology of theory (theōria) is deeply intertwined with its association to the concept of a spectator (theōros) – someone on the outside without “all the facts nor details.” It’s a term that gets thrown around a lot, and has not only shaped a kind of ersatz consensus reality, but synthetic narrative construction as well. We’ve heard the words “snowflake” and “oversensitive” thrown around, but what does it mean when our sensitivity only presents itself when confronted with the limits of our own status as human beings? The age of the star, the diva, the genius, of the masses passively consuming what cultural experts produced, has passed. Widely-available technological tools have rendered excellence once preserved for the few available to the many – we no longer have the possibility of even entertaining the notion that we are extraordinary or unique. This insecurity might manifest in telling yourself you hold absolute knowledge of the unknowable, that you’ve deciphered the Voynich Manuscript, that everyone is stupid – an idiot who doesn’t get it – except for you. You are the jester and your neighbors are all hackneyed pedestrians. You’re red pilled, and everyone else is blue pilled. You become annoying and didactic, bludgeoning anyone and everyone over the head with your total knowledge of unconditioned reality until you finally get recognized as the genius you are. That’s one outcome of the amatory fixation with info acquisition. The other one would be the open-ended autodidactic, an experimental examiner of information, drawing elaborate webs to spheres of nefarious influence. You’re a researcher, a wholesome hobbyist of Skinwalker Ranch, Djinn, the Paranormal, and the paranoid playing with models and counterfactuals. Bruno Latour wrote that critique had run out of steam, and one should be applying faculties to matters of concern over matters of fact. You are investing valuable time looking into mechanical errors deeply seated within objective functions of social virtuality to resurrect the myth and symbolic exchange vital to conscious life.

Megalothymia and modernity

I’ve been interested in conspiracy theories since I was a teenager. My initial interest in seeking alternative info came about during the Iraq war, in the aftermath of 9/11. Even at a young age, naive and without political or social conscience, there were things about events that just didn’t seem to add up. My distrust accumulated with each suspicious event and the possibility of a likelihood: there was no truth whatsoever to the claim that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction. I was one of the only students in my California High School to actively participate in protesting the Iraq War. Soon thereafter I entertained whether or not our politicians engage in pedophilic rituals at Bohemian Grove, that the international banks were colluding with world superpowers to bring about a one-world-government. When you’re young, ambitions are less shackled by the disillusion of experience, you haven’t succumbed to nihilism yet and you’re not encumbered by practicality. Megalothymia, this desire for distancing oneself from the norm, came in various watered down shades in the early/mid 2000s, the epoch of the hipster know-it-all, indulging in obscurity for obscurity’s sake. Anything popular was ostensibly bad, everything obscure was ostensibly good. Now that I’m older, I can see this is untrue, but this wasn’t necessarily a bad thing, it was a means of establishing some type of differentiation system using whatever historical tools were at my disposal. It inspired a kind of wholesome and youthful intrigue, that in itself seemed to be inseparable from the folk culture of America.

What passes as lore today is a cheapened hyphenation of its original social function, merely existing as a fix of the Sisyphean longing for universal recognition in a necropolis of dying transient culture. We’ve traded our private joys for TikTok hype houses and various forms of parasocial cruelty. Memories are exchangeable for short lived psychotic enthusiasm for objects with no identifiable quality, turning into shallow mass-graves filled with the skeletal remains of freshly-killed fads. We’ve seen time and time again what happens when the desire for mutual recognition gets unfulfilled – there is always a backlash. We got the cosplay fest of May of 68’ and we’ve seen everything from third world internationalism and “dissident” reactionary and progressive political movements get absorbed back within the margins. And this isn’t even new, we got the Waldensian response to the Veneration of the Saints in the 1200s, our version much more pornographic. So much of the critical discourse of the past ten years surrounds identity, how we relate to history, fictions, nations, and how identity relates to objects in moments of an increasing downtrend in the influence of singular subjects. This reductive criteria fails to reconcile the dilemma of identity as a feature of economics (shades of fixed and transient capital), technology and the state. As our own perspicacity has declined, any catch-all political solutionism of the 20th century and beyond has failed in its attempts to answer to the fragmentary cognitive predicament of evolutionary confusion beyond history. György Lukács once said that a key feature of modernism is the withdrawal of the subject from the struggle in the world; withdrawing from a world which he described as “psychopathic”. What place does lore or saga have in this modern era? If you have to create lore for yourself, chances are you’ve never done anything worth narrativizing in the first place, feeding the endless depository of context collapse like an intrusive thought that won’t go away.

Methodology, art and conspiracy

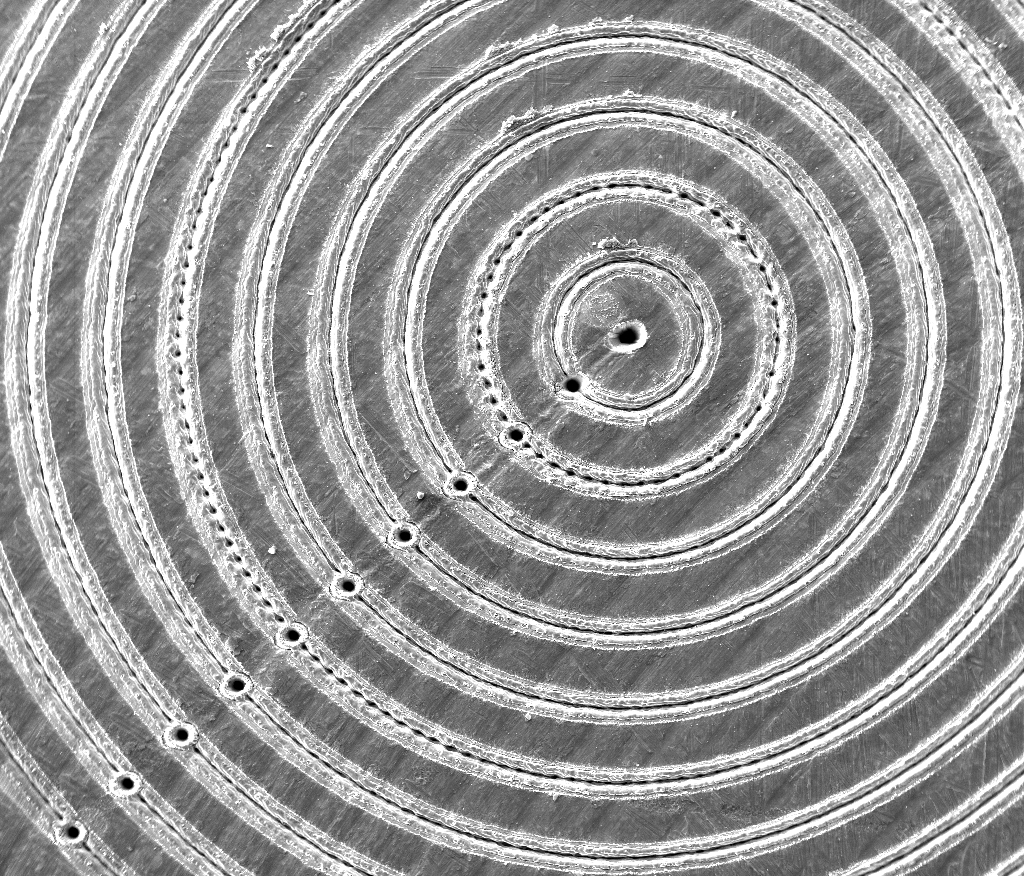

I go through scanned PDFs of Indiana-based holding companies from the early 1900s, looking for traces of engineering concerns, infrastructural influence, but most importantly, financial and political frauds and abuses of power. Each document has a beautiful, mystifying quality – the uncanniness of a defunct bank, mineral depository, or safe company logo. I message some of my parapolitical/theory/”research-head” friends, they show me a hat they found from that same bank from a vintage reseller on Ebay. I show them the ring I found in the desert, “HERCO” in 70s block letters, looking like it belongs on the side of an inconspicuous building on an industrial block hidden from the public gaze. It’s a safe company that changed hands many times over. I wonder how the business got started, I dig through the Internet Archive to see what I can find. The hard-contrast black and corporate informatics sprawls in schizoid assemblages of patent numbers, financial records, meeting logs, and hand-written notes. In something like this, you can possibly trace Samuel Bronfman’s Distillers Corporation all the way to British Arms Deals during the Iran Contra Scandal which was then somehow laundered through tax-exempt charity foundations. For me, this has a somewhat stabilizing psychological effect, given the current news climate. I can’t help but to see a kind of art in this stuff: a monogram combining link analysis diagrams, blown-out xerox’s, long books diving into painstaking technical detail about the technologies that mold and override social reality. These details merely exist as something comforting for reasons beyond words – a void of American understanding or Pierre Soulages’ black paint. One of the previous features of art, before context collapse, was that it was a negation of reality. Now, reality itself has collapsed into the unreal. The art of reality is the art of a hidden reality. We negate the features of everyday life through discovering what is real again because everyday life has become so unbearably fraudulent and exhaustive.

The neo-conceptual artist Mark Lombardi created what he referred to as “Narrative Structures” – intricate drawings consisting of interconnected lines, shapes, and text, meticulously researched and based on extensive investigations into various scandals, conspiracy theories, and political events. Lombardi’s drawings were intended to expose the hidden networks of power, corruption, and influence that shape our society. He drew inspiration from diverse sources, including news articles, books, court documents, and interviews to create visual representations of the relationships between individuals, organizations, and events. The artist’s works often focused on themes such as global politics, international finance, and illicit activities. Lombardi’s drawings allowed viewers to explore and interpret the intricate connections between people, corporations, governments, and other entities, revealing the often unseen forces that operate behind the scenes. He supposedly “committed suicide” in 2000. He gave a brief interview just before his passing, where he predicted his own murder. To what extent this is true, we really don’t know, but it does make for some interesting theories of its own. I’ve noticed more parapolitics enter the gallery (Trevor Paglan’s You’ve Just Been Fucked By PSYOPS) but this behooves the point. This stuff doesn’t need to be in a gallery, and appears to be a momentary zeitgeist for art world insiders to capitalize on while doing less of the exogenous work.

Snapping

The term “information disease” is not widely recognized or established within the field of medicine or public health. However, it can be understood as a metaphorical concept referring to the negative consequences or challenges associated with the spread and pornographic nature of digital media and images. This term was first explained in the 1977 book Snapping: America’s Epidemic of Sudden Personality Change by Flo Conway and Jim Siegelman. The book describes how various Information Diseases (IDs) cause an emergent phenomenon of “snapping” – people who, while seemingly normal one day, succumb to a kind of epistemic break not from real-life experiences, but electronically through television, media, computers, and other forms of reality-layering that convey a kind of shallow Everything All At Once. This most commonly leads to a crisis of identity, a heightened state of awareness, people as “mere holograms of the society they inhabit” and at worst, acts of dream-like violence, where the subject has lost the capability to determine whether or not they’re awake or dreaming.

I can’t help but to recall what Byung Chul Han wrote about the violence of positivity, wherein our addiction to likes, validation, feedback, and instantaneous rushes of data (mostly self-reinforcing and auto-referential to the core) is exhaustive in its saturation and abundance, how it yields a kind of burnout, is constantly reinforcing its own excessive drives. There is no closure, you can’t turn it off, it’s an escape into what is purely subjective. The grand conspiracy of parapolitics has an enchanting, comforting quality – it erases the subject by elucidating these drives. MK Ultra or White Propaganda gives a framework of identification so that we can at least pause and say “let’s not go there”. The self-regulating mechanism of digital information always seeks to bring itself back to a desired set-point, to keep things “feeling positive” – even when they’re harmful or destructive.

Folklore at end of history

If history is in fact ending, then it has one defining characteristic and that is endless change. Change has become its only stabilizing feature. One of the maxims most often repeated is that we need change, things need to change, etc. But what we really need is not change but to change the change – to escape from the change itself. If there’s an existing ersatz utopia, it’s a place with perceptive change. It’s where rage bait, trend-cycles, the expanse and proliferation of words and data sutured together in a Midjourney penetrated spectacle, have a minimal placement upon object-subject relations. This flurry of change converts lived experience into lived capital, it reduces the experience to a mere simulation of aristocratic satisfaction without any of its traditional amenities.

To see where the concept of folklore could possibly fit into this, we should start with a bit of etymology. The word folklore, a compound of folk and lore, was coined in 1846 by the Englishman William Thoms. The second half of the word, lore, comes from Old English lār, “instruction”. It is the knowledge and traditions of a particular group, frequently passed along by word of mouth. The word “folk” has come and changed definition over time; initially being applied as a descriptive of peasants and the uneducated. Folklorist Alan Dundes wrote in The Devolutionary Premise in Folklore Theory that “Folk is a flexible concept which can refer to a nation as in American folklore or to a single family.” The notion that folklore could be revised and devolutionary was challenged by Elliot Oring, because he regarded folklore as the mutilated fragments of culture, culture that has devolved, degenerated and decayed.

What separates folklore from other cultural traits is that it is maintained through force-of-habit. In a life story or story of one’s life, people tend to describe themselves as a person with a history, that is, as someone who has been involved in some more or less remarkable events, encountered remarkable decisions to make, or had some sort of remarkable personal experience. This was the narrative function; a reminder that serves and ignites the capacity for strength in each and every one of us. It’s almost impossible to imagine the purpose of a life story or a story about one’s life without any sort of coherence, but the incoherent life story is the strongest personal branding signature we have today. Thus, the end of “folk” i.e. commonality in folklore gave way to what Gen Z frequently refers to as “lore”. It’s a kind of aesthetic kitsch mythology in absence of shared experience, mettle, determination, and overcoming.

The tsunami of personalized information overwhelms us: a frenetic onslaught of communication via text messages, Twitter, Instagram messages, Gmail, various group chats disturbing our focus and attention. Everything from politics to art becomes absorbed and indistinguishable, trying to outcompete each new piece of information in a quest for relevance. The caveat here, is that each time you do this, you add a new record of information wherein the machines can summon and identify it as a point of access. The outcome is a loss of opposition entirely.

Parapolitics and the Oklahoma City Bomber

One of the information resources that has brought me peace of mind is the expanding interest in parapolitics podcasts (Subliminal Jihad, Pseudodoxology, etc.), Twitter accounts, TikTok videos, and more. Parapolitics, likely coined by Peter Dale Scott, refers to the study of hidden or covert political activities that operate outside the traditional political system. It involves examining the influence of non-state actors, such as intelligence agencies, organized crime groups, and other clandestine organizations, on political processes and decision-making.

The book Aberration in the Heartland of The Real by Wendy S. Painting, a deep political investigation of Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh, not only describes various sociological patterns of lone wolf gunmen. If anything, the book describes how knowledge of the conspiracy and shadow network can liberate us from the paradox of empty and performative gestures towards the proactive manifestation of radical concepts, artworks, etc. There’s no longer a criteria to judge things individually: criticism as a vocation has been in its death throes for a long time. This is partially due to alternative sociology addressing many of the patterns that exist within society. “What is a zeitgeist? What do separate actors seem to have in common? What motivates them not individually, but contextually, as a single operating unit?” Many of these questions are also prevalent in the way we view art. Art is not gauged anymore on how it stands alone (with various exceptions like abstract expressionism that has also been co-opted for state ideological functions) but in context with other things. This is what Beuys referred to as “Social Sculpture”: a gesture towards utopianism by way of aesthetic, counter-political, actions.

Timothy McVeigh also known as The Oklahoma City Bomber led a fairly standard albeit fractured American existence. He grew up outside of Buffalo, New York, was shy, diligent, by all accounts a decent citizen. He also grappled with the fraught relationship of his parents, his father submissive to an alcoholic, adulterous mother who would fight all the time and eventually abandon the family. He was nerdy, interested in computers, the early advent of the Internet and eventually hacker culture. He also began to hate women, seeing all of them as analogous to his philanderer mother, only on occasion having intercourse (with women who were either married or much older). He became interested in prepper culture, a standard social phenomenon brought about by the Cold War and various media portrayals of invasion from the USSR such as Red Dawn and Soldier of Fortune Magazine. He then became obsessed with the Turner Diaries, an infamous post-apocalyptic fantasy written by William Luther Pierce, founder of the neo-nazi organization National Alliance. Various accounts claim that racism had nothing to do with McVeigh’s interest in the Turner Diaries; his military cohorts and past coworkers had described him anywhere within the range of “would hang out with anyone, tolerant” to “mildly bigoted”. What did speak to him was the fantasy of collapse, of a futuristic wasteland where an oppressive federal government referred to as “The System” would be overthrown.

McVeigh was sent to an experimental platoon called COHORTS, which became subject to various forms of call-response and conditioned reflex activities. He received a series of shots, which caused him to go to the Army dentist a total of 75 times. One of the most harrowing details in the book describes his ascension to Top Gun, head of what he was told was a highly prestigious deployment, though secretly used as cannon fodder to test the experimental Bradley vehicles on the front line. They were then told by a ranking official they had an up to 90 percent chance of dying. Following the bombing, McVeigh was apprehended and charged with multiple federal offenses, including conspiracy to use a weapon of mass destruction, use of a weapon of mass destruction, destruction by explosive, and eight counts of first-degree murder. He was found guilty on all counts in a federal court trial and was sentenced to death. During the trial, he admitted to carrying out the bombing as an act of revenge against the federal government for its handling of the Ruby Ridge incident in 1992 and the Waco Siege in 1993.

Rap’s First Serial Killer

I was watching a three and a half hour YouTube documentary on the deceased Chicago Drill rapper King Von called Rap’s First Serial Killer. Von (real name Dayvon Bennett) was a driller and a shooter who, according to various second-hand sources scoured from the Internet, video footage and cryptic but overt admissions on Twitter and in his tracks, had racked up “at least eight bodies”. He made references to “cereal” (pieced together meaning serial killer) and named dead opps in songs. These references were meticulously pieced together by fans and 4chan Internet shoops, which built a mythology people could follow and invest in. This narrative unfolded to legitimize a rap career. He put in work in the streets as a shooter in Chiraq, hence why years after his death you can still invest in a lengthy documentary and millions of people will want to watch it. Ethics aside, the commitment to the acts of consequence are clear to see. Why else would we be endlessly fascinated by both serial killers and rappers?

With the collapse of social cohesion and technology that assimilates any connection to the past which then gets converted into surplus identification, there are still people trying to uncover narratives that exist but aren’t shared or talked about. Some of it is far-fetched, not all of it stacks up, but it’s an alleviation from the endless auto-referentiality that doesn’t yield or terminate in anything other than a few moments of hype and subsequent exhaustion. Particularly over deep geological time, the expansion of linearity is the consummation of nihilism: it behooves progress and exit. It’s no longer even worth doing a critique of any of this. We can just slow down, read two pages over the course of two months, burn CDs for our friends and exchange xerox copies of information that command deeper investigation. Hardware still exists – we become conspirators as the machines work faintly in the background on our behalf (or not).