On the limitations of language, and the limitless lust for what lies beyond

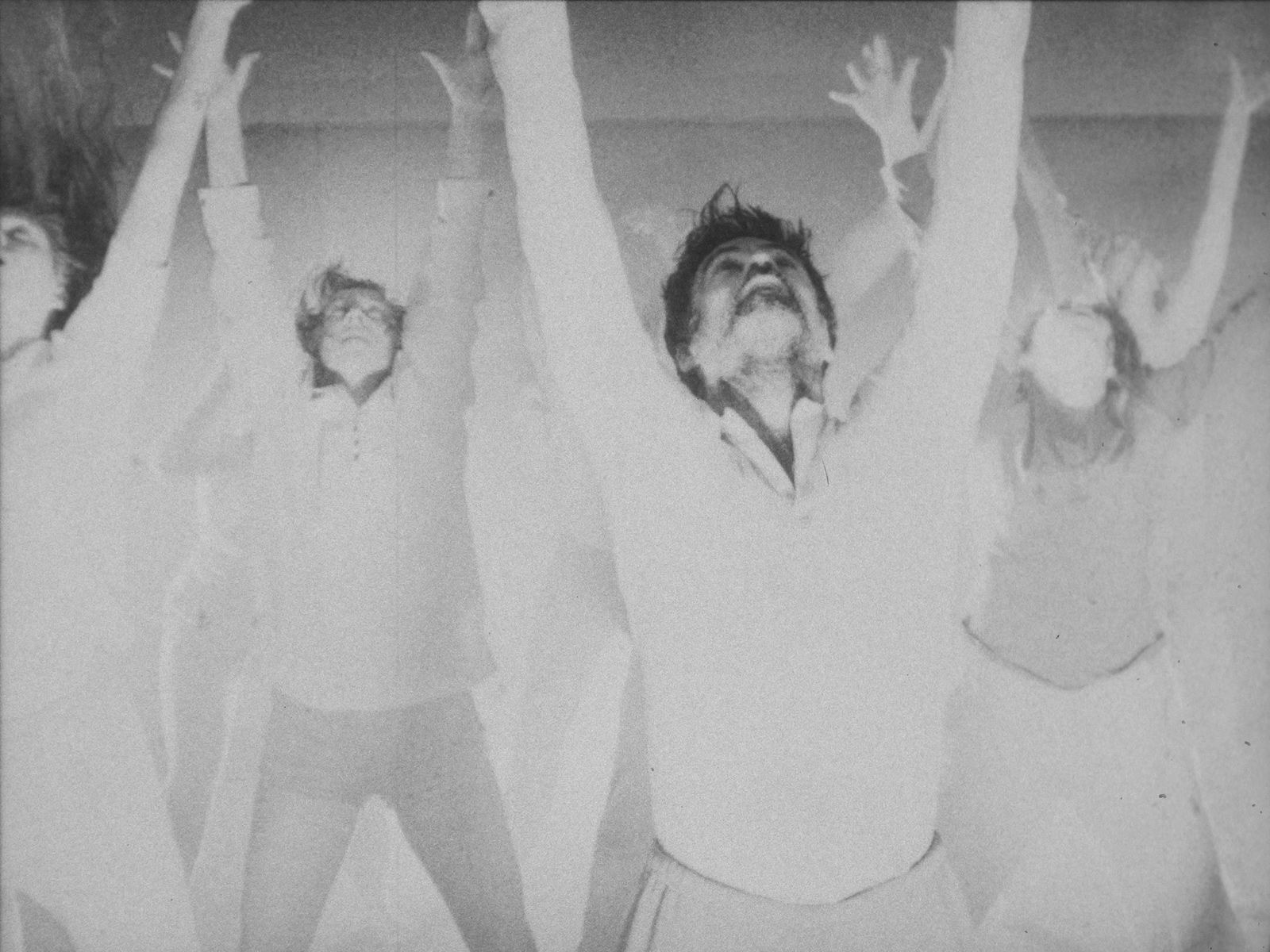

Canadian-born and Berlin-based artist Jeremy Shaw has dedicated his practice to the notion of altered states. Earlier this year, he exhibited the work Phase Shifting Index for the first time with a solo exhibition at Centre Pompidou. The piece continues the artist’s work on science fiction inspired pseudo-documentaries set out at different points in the future to explore humanity’s need for faith and belief. Following the Quantification Trilogy, Phase Shifting Index imagines the behaviour of different countercultures trying to break with their faithless societies through diverse choreographed practices.

Nora Hagdahl: If I were to try to summarize your practice, I’d say it’s about merging the disparate experiences of ecstasy. Drawing from drugs, religion, dance, and science, I understand it as your desire to fuse higher states one can achieve therefrom.

Jeremy Shaw: I want to look at the universalities around the notion of transcendence, of attempting to transcend – however that may be defined. Whether it be through drugs, dancing, meditation, religion, technology. Humans seem to have an almost inherent urge to reach higher states of being. I’m fascinated by this seemingly universal human desire, as well as the scientific attempts to explain it.

NH: Do you believe it’s inherent in human nature to seek spirituality?

JS: I think it’s an age-old human trait to look for something beyond the here and now, no matter how you go about doing that. Cavemen danced around the fire into some type of fervour. What is defined as spiritual is another story. All these words get quite nebulous when it comes down it. How you go about in trying to locate a higher state, or get somewhere outside of your given reality, depends on numerous factors in your life and beliefs. But I’m generally interested in the disparate paths people take, as they aspire towards some type of transcendence.

Humans seem to have an almost inherent urge to reach higher states of being

NH: Where did your interest in transcendence start?

JS: I think it started when I was really young. I used to play these games with friends where we would choke each other in order to black out. It was an early entry into the world of altered states for me. I loved waking up from it in this strange, dream-like daze. A key moment was definitely taking LSD for the first time. I remember being fourteen, lying in the grass at a park by my school, staring into the beyond and really having my mind blown – in the true sense of that term. I was totally enamored with the world again and filled with a million questions. Barely out of being a child but shot back to that sense of wonder that children have. I was also raised catholic, so from a very young age there was the notion of God and heaven, sin and guilt and something greater than our own existence. Through growing up and making art more and more seriously, I started becoming interested in other people’s experiences, other people’s beliefs and practices and how all these things eventually lined up for me in some way.

from a very young age there was the notion of God and heaven, sin and guilt and something greater than our own existence

NH: Do you look for something beyond yourself?

JS: Absolutely. But I’ve always been both a believer and a skeptic. I think that partially stems from being raised religious, and then realizing that the religion I was raised under didn’t want me. You learn very quickly about the paradoxes of these structures when something about yourself goes against the rules. I think this is partially what instilled a deeply inquisitive nature in me in regards to these topics. This carried on through all phases. As much as I wanted desperately to attain some kind of transcendental experience, I was always questioning it while it happened – even that first time on acid. That is how one of my early works, DMT functions; to have a profound psychedelic experience and then, minutes later, try to dissect it. Affect and analysis became a thread throughout so much of my work.

NH: Tell me more about that work.

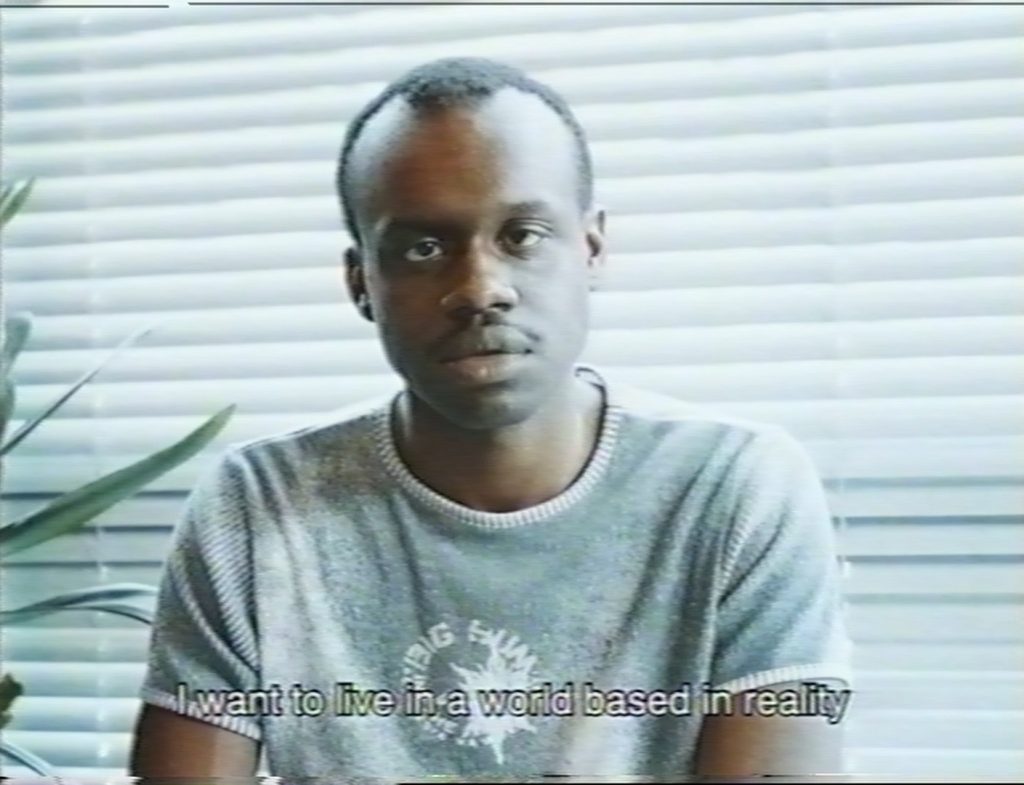

JS: I filmed people, including myself, taking the drug DMT. DMT hits you within about 30 seconds of smoking it, lasts for around 6 – 15 minutes and then leaves you just about as quickly. You go from being sober to being as high as you’ll ever be – like truly mind-melting, death-of-ego level of high – and then back down again in an incredibly short duration. The only instruction I gave people was to, as soon as they felt like they were coming down, attempt to describe what happened. In the films, you see people high on the drug, with their immediate post-trip descriptions (in generally very broken English) subtitled below. It was my idea to combine a somewhat austere document of this incredibly insular, mind blowing psychedelic experience with the attempt of some kind of critical analysis by the subjects themselves. A kind of conceptual version of psychedelic art.

NH: There is something about trying to explain an experience like that; as much as it is profound, it is also intangible. It lies beyond words.

JS: Language is very limited, isn’t it? Our ability to explain these totally profound experiences is delegated to only a certain amount of words, which can be quite frustrating. But I find it fascinating, as well. There are certain things we just can’t translate to each other in words. And it’s not necessarily just with psychedelics and spiritual experiences, but even with certain emotions, like love, for example. They are often falling outside of language. Making DMT immediately pointed at this for me – how fraught the translation of profound experiences were, which is something I’ve really embraced and celebrated in works that followed.

NH: Do you believe in a world besides the one we experience with our senses?

JS: I believe that we aren’t able to receive everything that is potentially available to us in our day-to-day existence. Through experimentation with drugs, meditation and various other cathartic experiences over the years, I think I’ve been able to witness certain… channels into something I perceive as being beyond. Whether that means there’s life after death or multiverses or anything else, I’m not sure. But I would certainly question our everyday reality as the definition of our existence. We simply can’t ingest and process everything that is potentially available for our perception of reality.

NH: Much science today points to that right? Quantum physics, for example.

JS: Absolutely. And there is so much faith involved in quantum physics, which is something I find incredibly interesting. There is a lot of jumping to big conclusions without any hard proof but one’s faith in science. This is why I think science and spirituality are getting closer and closer in conceptual ways.

A kind of conceptual version of psychedelic art

NH: Something I picked up, when looking at your work Phase Shifting Index, is this conflict between rationality and spirituality. That work, along with other films included in the Quantification Trilogy, touch on this ancient question of mythos or logos. In my opinion, your films make a claim for mythos before logos and want to question rationality – a critique of the human that could be put down in numbers and calculations.

JS: There is an overarching theme in the films known as “The Quantification”, which is a scientific discovery that has isolated spiritual experience to an identical set of synapses firing in the brain of all humans. The groups in the films have subsequently discounted spirituality entirely, stopped believing, stopped having faith. Instead, they have become dependent on a type of virtual reality replication of a spiritual belief system. The various groups in Phase Shifting Index are all attempting to get away from this technological stranglehold that has turned humanity apathetic. I’m not sure if that’s necessarily a critique on rationality or a proposition for more conversation to take place between these two sides – and the potential for more balance. I’m into both mythos and logos.

NH: It made me think about all these algorithms set up to foresee human behavior, mostly, to serve capital. We live in a society that benefits from humans being predictable and act in accordance with statistics. Modern society basically wants to put people in molds. Spirituality could be a rupture in that, right? I at least tend to think about faith and belief as unforeseeable, that it works in irregular and illogical ways.

JS: For sure, especially if it’s truly embodied and experiential. One of the major questions I wanted to raise using this idea of “The Quantification” throughout the films, was that if we lost the ability to believe, or to have faith, would that have some kind of evolutionary effect on humanity? Is this notion of searching for transcendence crucial to our existence? What would happen to the species if we truly lost this urge?

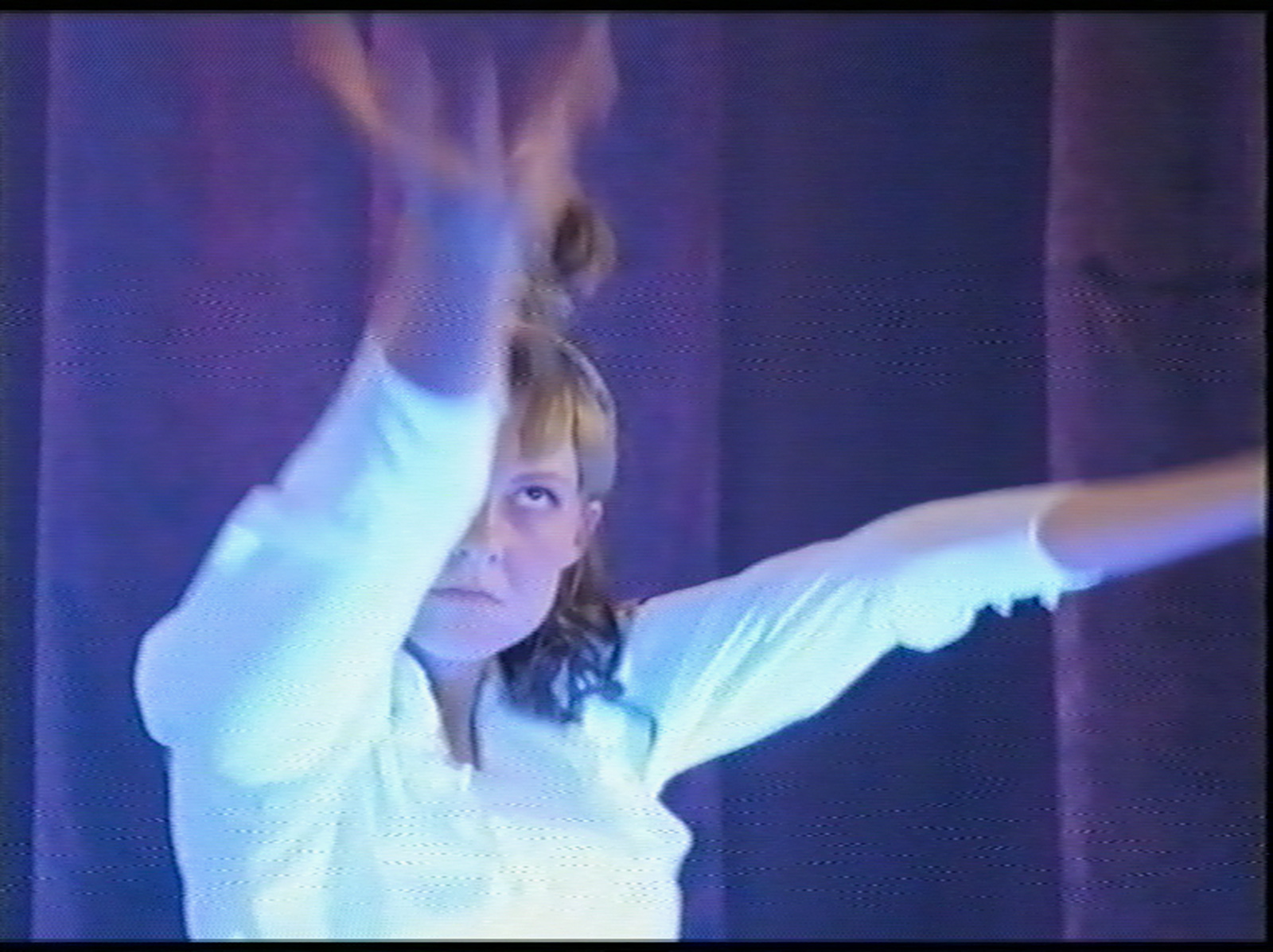

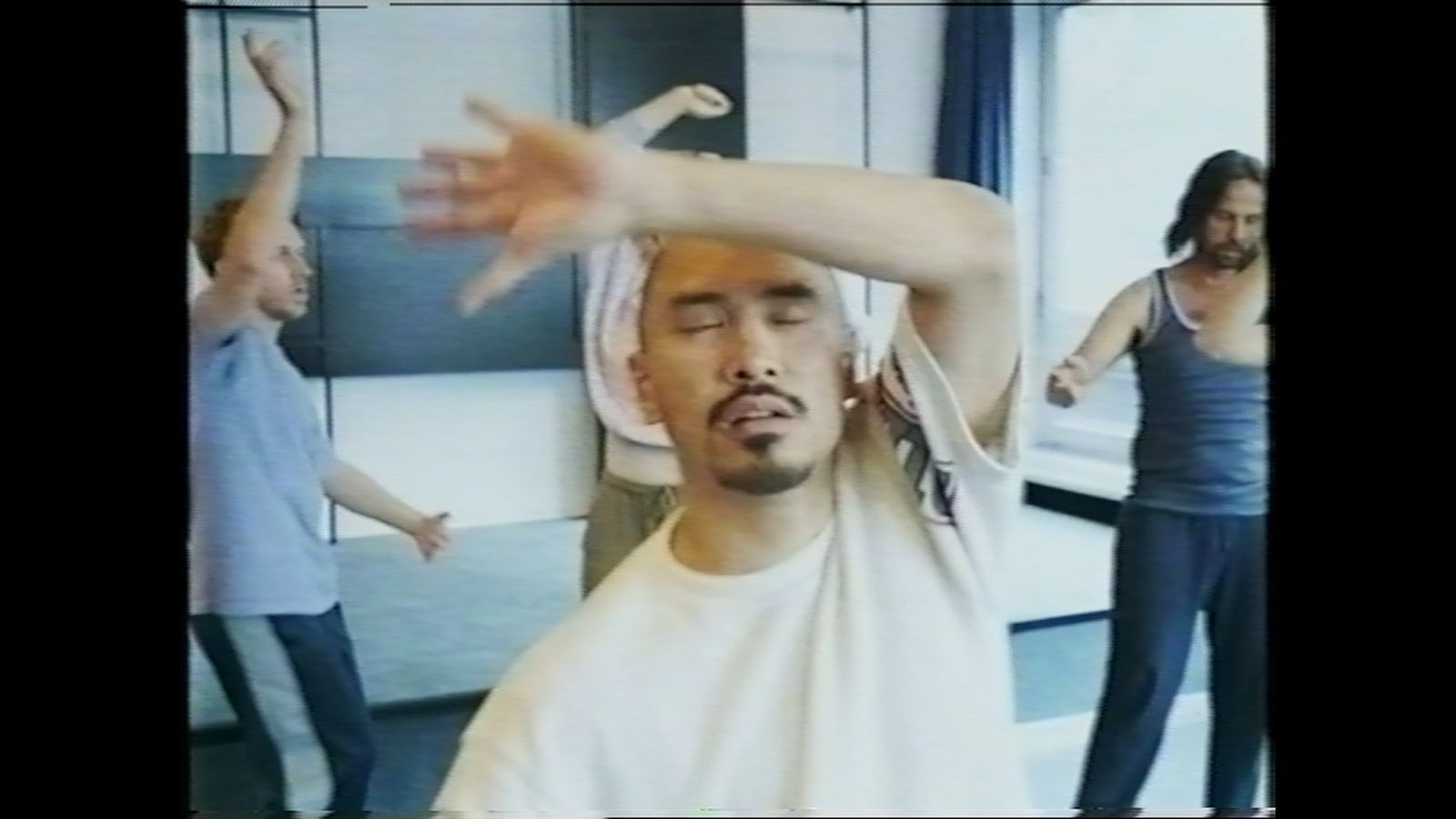

NH: Phase Shifting Index is a seven channel video installation. Each film in the piece operates on their own and they all appear to be found footage with an aesthetic spanning from the 60s to the 90s, featuring groups of people engaged in some kind of movement practice. Dance has been something you have explored throughout your work, for example in the piece Variation FQ, where you filmed the transgender vouger Leiomy Maldonado. What fascinates you about dancing?

JS: When it comes to the notion of altered states, dance is one of the most common forms. It’s something I love to do and I’ve always found it very captivating to watch other people dance. Watching someone work themselves into a trance through movement has always put me into a kind of trance as well. Dance can function as its own highly personal belief system. If you’re not religious or practicing a spiritual routine of some sort, dancing can easily fill that void, consciously or not.

I think I’ve been able to witness certain… channels into something I perceive as being beyond

NH: The workends with the seven different narratives merging together through a synchronized choreographed routine. The concept of time has always been an aspect of your work that really interests me. In Phase Shifting Index, you’ve created these different narratives, set out in different times. At the end of the work, all these disparate stories are fused together. To me, that points to some kind of universality across time.

JS: There’s a constant manipulation of time in my work. When creating this cross-temporality of Phase Shifting Index, making videos that seemingly come from different decades and eras to be presented together, I was thinking about the co-existence of parallel realities. In the films, each group aims to somehow induce a new reality for themselves; trying to escape their present state through various combinations of movement and belief. Time within their worlds appears linear, but the existence of these multiple timelines playing simultaneously points to something else. This is illustrated with a moment of synchronicity in the installation as they get caught in a cross-temporal choreography – all seven different groups on their time-specific media dancing to the same music at the same time – or at least what is the same time within our reality as a viewer.

NH: For me, it was like jumping off the timeline, you know?

JS: I wanted to go even further with this notion of synchronicity in the various timelines, so I introduced a real rupture in the media of each that takes them from outmoded forms of VHS and 16mm, to the very contemporary digital datamosh output. At this point various subjects from the various groups depicted start crashing into each others’ screens – as if the synchronicity had become a physical reality between them and they were now all inhabiting the same world, or timeline.

NH: I’m thinking about the technical elements that enforce this feeling of ruptures in time. The sense of a distorted timeline is amplified though strobe lights or when the scene culminates in these distorted images where characters jump from one screen to the other in this kind of glitchy aesthetic. I remember that you end Liminals in a similar way.

JS: I guess as it’s how I’ve always defined altered states, as something that distorts your ability to gauge time in reality. Strobe lights are very distorting of time and space. Slow motion has also been something I’ve used consistently throughout my work for years, as well creating additional, often juxtaposed soundtracks. In the past few years I’ve become increasingly interested in creating new visual effects of my own as an attempt to actually illustrate the abstract nature of altered states on screen. I’ve often employed many of these tropes and amplified them as much as possible.

NH: From what places do you draw inspiration when it comes to the way you work with film as a medium?

JS: From growing up watching music videos and science fiction and horror movies, for the most part. It’s like taking what you’ve seen work effectively in mainstream cinema for the representation, or attempted incitation, of altered states and amplifying it as far as it can go. But also from skateboard videos, you know? There’s a pretty large range of influences in my work, but skateboard videos were actually an early example of combining disparate elements together – and in a somewhat modest, or achievable way.

it’s how I’ve always defined altered states, as something that distorts your ability to gauge time in reality

NH: I also wanted to ask you about this idea of fiction versus reality, which is visible in many of your works. All the films in Quantification Trilogy as well as Phase Shifting Index are these pseudo-documentaries. I know that you worked with real archive material for Quickeners, but all the other films instead mimicked the style of found footage. The line between real and fiction becomes completely blurred. You also work with this made up language. It sounds like English but isn’t, which creates confusion for the viewer. What are your thoughts on that?

JS: For Quickeners I worked with an archival film from 1967 about Pentecostal Christian snake handlers. It included an amazing cathartic scene where they start dancing ecstatically and passing poisonous snakes around. In my earlier days, I would have simply worked with that moment and reworked it into some sort immersive, music-video like installation, but I had come to a point where I wanted to take the proposition of my work further. So, we invented a way of scrambling the language of the subjects on screen so that I could subtitle it with the story I wanted to tell. The entire narrative was reverse-engineered out of this pre-existing material. I found this strategy very effective, so I began going about making the subsequent films look archival and shooting them as if they were documentaries, and then sculpting the narrative out of that raw material. As a result, I was able to illicit a suspension of disbelief and belief. I really enjoy finding new ways to manipulate the expectations of the viewer. I love it myself when I get confused, tricked or manipulated by art or film, like even with those M. Night Shyamalan movies where there is a huge twist in the story. I love that, especially when I don’t figure it out before it happens.

NH: So in a way, you turned away from reality, as it was not enough to tell the story you wanted anymore?

JS: I guess in a sense, yes. I mean, I’ve never been interested in making straight-up documentaries, but I also never saw myself making narrative feature films, which I feel I’m almost on the edge of these days. The propositions seem to be getting more and more elaborate and extreme though, so let’s see. But yeah, I’m much more into potentials than finites. I’ve always been drawn to film and music because of the explosive potential for imagination, and it’s the same with art. I don’t think we shouldn’t shy away from the spectacular.

Language is very limited, isn’t it?

| Photography | Phase Shifting Index, 2020 |

| Video stills | courtesy the artist, König Galerie, edit Caitlyn Lee |

| Words | Nora Hagdahl Arrhenius |