An interview with curator Guillaume Désanges

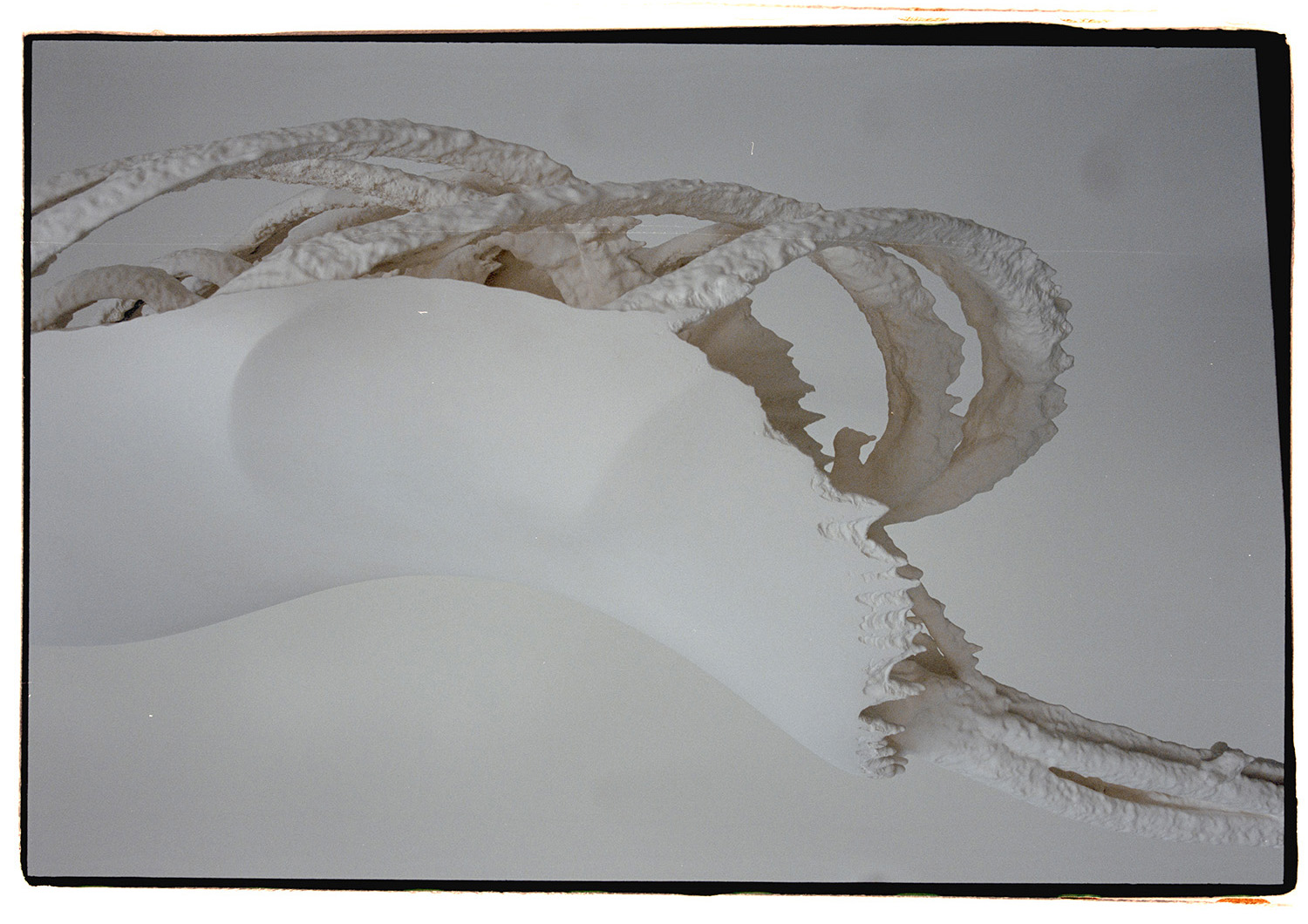

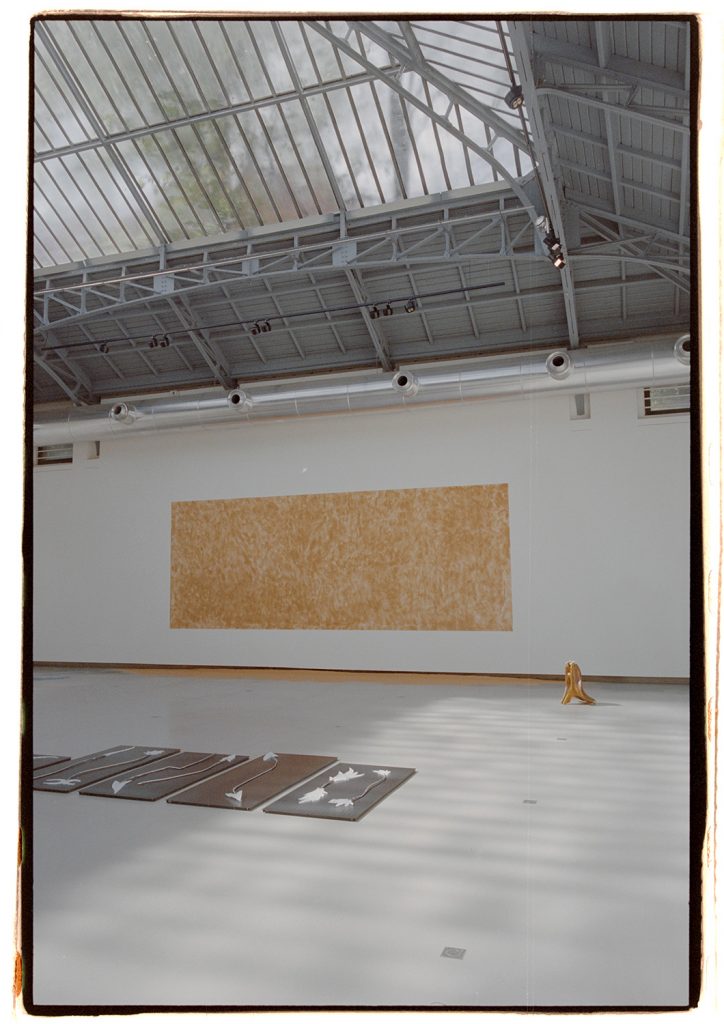

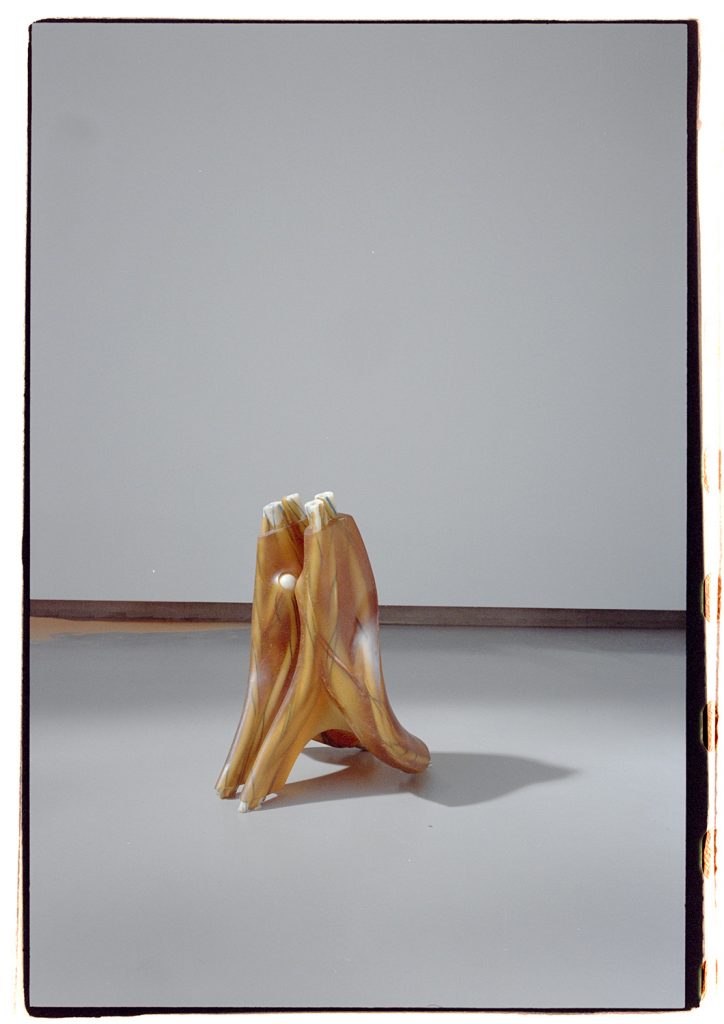

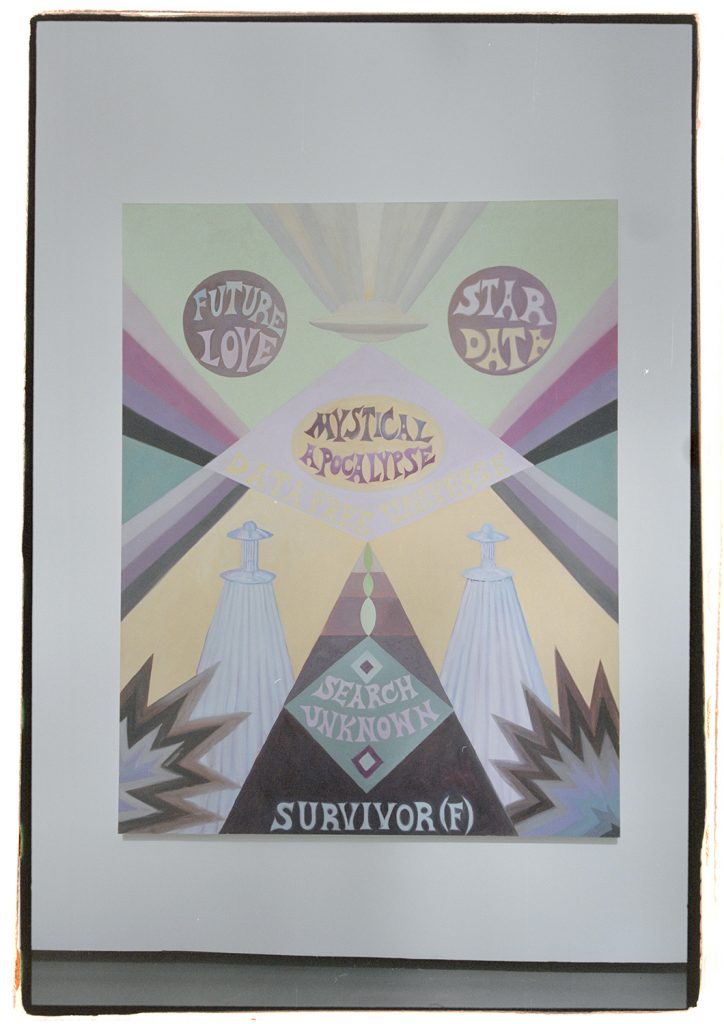

Earlier this year Guillaume Désanges was appointed new chief curator of Palais de Tokyo in Paris. We talked to him about his most recent exhibition at La Verrière, a Brussels gallery run by Fondation d’entreprise Hermès. The exhibition put emphasis on science fiction and new narrations through the eyes of several young, emerging artists, with some exceptions – Pierre Huyghe, Paul Thek and Suzanne Treister all appear. Walking into the show I feel as if I’ve entered an archeological site from an unknown time in the future. Roy Köhnke’s work Suspended Consumption #1 is hanging from the ceiling as an alien cadaver with chords smudgily coming from the body and touching the ground, like a brutally butchered piece of meat. On the floor as if just excavated are Tarek Lakhrissi’s weapons, spears and axes in metal with edges made of glass. The exhibition’s aim is to imagine the world after and beyond though the world of fiction.

Nora: Do you want to start by telling me a bit about the exhibition and your ideas behind it?

Guillaume: There was a lot of ideas behind this exhibition, both intention and intuition. For a long time now, I’ve worked with the question of ecology – a theme that I explored through the series of exhibitions called Matters of Concern, exhibited here at La Verrière. One could say this exhibition displays a step in that research, coming to the conclusion that we need new narrations – new stories – to be able to change the world, or even imagining change. The stories that we’ve created determined the course of the Western world, they mark our lives at their essence – so if we want to change the world, we have to change our stories. I was very inspired by Donna Haraway and her way of working with fiction to imagine new world orders. I was also drawn to science fiction, as another way of telling stories where rules are reversed and predetermined conditions or relationships don’t exist, as with Ursula K. Le Guin’s famous “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction”. The great stories of Western culture have been about following a winner or hero, who dominates through violence or exploitation. Ursula K Guin was more interested in the stories about the person filling up the vessel than the ones about the man chasing the mammoth. For me, that’s another type of revolution. This exhibition was an attempt to re-write the story and to try to find new narratives about our world through fiction. I wasn’t interested in the solutions that are already there, the exhibition rather delves into the unreal as an attempt to widen the possibilities of what our world could be.

N: You say you see this exhibition as a continuation of the previous series of exhibitions called Matters of Concern, where different artist such as Lucy McKenzie and Babi Badalov or the architect Gianni Pettena worked around questions of the material and the relationship between humans and the natural world. The title is borrowed from philosopher Bruno Latour, who distinguished “matters of concern” from “matter of facts”, where the former are the questions people gather around, that spark discussions or emotions. Latour believed that matters of fact are increasingly exchanged for matters of concern in today’s society. Can you tell me a bit about that series of exhibitions?

G: I was thinking about the ecological issues, a topic that I think is difficult to escape today. I tried to see how we could create things having that in mind. I love art and I don’t want to stop producing, so I wanted to look at less cynical ways of production, that were not based on overproduction but more on specific attention to a material, or a transformation of an object from one thing to another. It’s about having respect for our environment, to say that we are a part of nature, not here to master it. In the exhibitions I worked a lot with artists that were humble with their use of material or that were interested in loading the art object with other functions than being merely decorative or beautiful. Modernity has worked on denying any function for art – for me, that’s not ecological. When I started working in the arts, I had also the idea that art shouldn’t have to serve any purpose, but as reality changes I had to change too. It’s not about denying beauty or aesthetic things, but I think an object can be different things at the same time. I’m interested in objects with a slippery identity, that can be a therapeutic object, a political object, a ritual object and an art object at the same time. I think denying any function to art has been a way of depoliticizing the arts – we wanted art to be outside of the vulgar reality. Now I think it’s much more interesting to find relationships between the two.

N: The whole idea of minimalist art was about not pretending to be anything else than an object, to not be representation at all. I think there is something quite radical about denying art any function in a capitalist society, where everything has to be of necessity. There is something in the act of just not having any meaning or purpose, to merely be beauty that I think equals resistance today. But as you say, on the other hand one can say we have to be more resourceful with the objects we create.

G: I don’t think art is useless and only a luxury product. I think it has a lot of functions. Of course, it’s not only functional, but I believe it can heal and create emotions, and maybe in a more political way, change the way people think and behave.

N: In the press release you write that the role of the artist is to imagine the future. What do you think is the role of the artist today?

G: Maybe that’s a bit reductive to say… Artists are the champions of imagination; they can create worlds from nothing. The artist can show us how we can create something, hence how we can change something. I think it’s why I feel artists has such a central role in society.

N: In the exhibition there are quite a few young artists. What was it about their artistry that you felt was interesting?

G: The younger generation already invent new worlds in our reality with redefining the relationships to nature or identity. In that way, they are more or less consciously referencing the ideas of Le Guin. When teaching in art school, I was talking to my students about the condition of their generation, socially, politically and ecologically. I think it must be hard to hear about how the world is disappearing at the same time as we know that the first immortal person probably is already born. Our time is paradoxical.

N: I think this idea that you can make up your own reality is something that marks my generation. We’ve realized that the dominant narrative is just a story like any other, it’s breakable, and we can make up our own stories. I also feel like I can see that in art, where the previous generation was very interested in depiction and to describe reality, I feel like younger artist are more into escaping it.

G: That is true, we’ve had a lot of art that is about knowledge production – research-based art. It was needed at a certain time. It was a lot about the blind spots in history, and not totally separated from what we see now, it’s a continuation as it was also a way to change narration. But I think this new generation of artists don’t want so much to be professors. They don’t want to teach and share knowledge, they want to teach and share imagination and fantasy. This show wanted to grab that spirit. The artists in the show are not commenting on reality. They are not criticizing directly reality. Instead, they propose another possible reality using the tools of science fiction.

N: What are the possibilities in science fiction for imagining the future?

G: I think the world is so chaotic, it’s very hard to imagine the future from the present. You have to go somewhere else to be able to imagine what the future could look like.

N: Like jumping out of the narrative to look back on it?

G: I read about how the French military was hiring science fiction authors to imagine the scenarios of tomorrow. It’s so unpredictable so we have to use our fantasy, there is no other way.

N: Do you believe there is any downside to embracing fiction or the alternative narrative? I was thinking about the work from the exhibition by the collective La Satellite that was playing with pseudoscience and creating an alternative story about how life occurs. When it comes to topics such as the ecological crisis, it’s important that we have one collective story about what the problem is, and that we can distinguish true from false. Is it problematic to let pseudoscience and real science merge?

G: I don’t think so, because I don’t believe there is a pure science. Science is always made from a certain position, it’s created. There is always a fantasy in science, even the science we call real. I’m not against science as it is, and I am personally quite rational, but I just think we can make it broader, larger. For me it’s about bringing things into the sphere of knowledge that previously have not been part of it. It’s about broadening the field of knowledge to include spirituality, magic and things that are considered irrational. It’s about including all knowledge and philosophies, without hierarchy, as tools to prevail reality.

| Photography | Frida Vega Salomonsson |

| Interview | Nora Arrhenius Hagdahl |